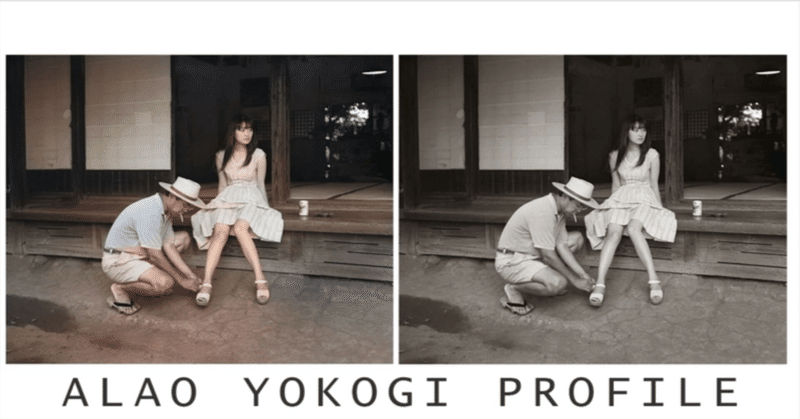

ALAO YOKOGI PHOTOGRAPHS PROFILE ENGLISH EDITION

"I started as a freelance photographer in 1975. I have worked in various genres including advertising, fashion, nude, editorial, documentary, and commercials. In 1994, I visited Vietnam for the first time and have traveled there multiple times since. I have produced photo books, non-fiction works, and novels related to Vietnam. From 2009 to 2017, I was responsible for the movies and still shots for the TV program 'Traveling the World's Roads'. Recently, I've been involved in digital photobook production projects and have also ventured into the NFT art scene."

ALAO YOKOGI PROFILE ENGLISH

In March 1949, I was born in Kounodai, Ichikawa City, Chiba Prefecture, neighboring Tokyo. My father was a crime reporter for the Asahi Shimbun. The place where I was born, Kounodai, is a historically significant location on elevated ground. Within Ichikawa, it was a town blessed with a natural environment, reminiscent of the countryside.

Before entering elementary school, I attended Kounodai Kindergarten, which was run by Ene Paulus, a female missionary who came to Japan in 1919 during the Taisho era. Although she returned to her homeland during the Pacific War, she came back to Japan after the war, disregarding the orders of GHQ, and reopened churches, orphanages, and the kindergarten to aid a turbulent Japan.

The kindergarten was located on a hill overlooking the Edogawa River. It was a spacious place, remodeled from a two-story wooden former army barracks. It was filled with large toys sent from the American Lutheran Church. That space alone felt like a prosperous America.

Every Christmas, a nativity play was performed. I sang hymns without understanding their meaning, like "♫ The Lord has come." As a young boy in nursery, I played Joseph, and in kindergarten, I played one of the Three Wise Men with a line that said, "I offer you frankincense."

Back then, Paulus's Kounodai Kindergarten was not officially recognized. So it was like a private school, brimming with a free, Americanized atmosphere. When it was officially recognized in Showa 33 (1958), it adopted the standardized system like other kindergartens in Japan.

Ene Paulus was born in North Carolina in 1891. She was the sixth daughter among nine siblings. Their father passed away when they were young, and while they weren't wealthy, their mother managed the vast farm they had, ensuring all the siblings graduated from college. Ene's older sister, Mode Paulus, had long dreamed of becoming a female missionary and had always wished to go to Japan, which she read about in books. By the time her wish came true, she was 29.

Influenced by her sister, Ene, who was both beautiful and intelligent, studied theology at Columbia University. After graduating, she was torn between going to impoverished Africa or aiding in post-WWI Japan, where she heard of rampant human trafficking of women in rural areas. Ultimately, she chose Japan, where her sister was already working. Initially, she assisted her sister in Kumamoto, Kyushu, before moving to Ichikawa City, Chiba Prefecture, in the Kanto region.

I learned the truth about Miss Paulus, or Ene Paulus, in 2004 while researching the last days of the photographer, Robert Capa. Until then, I had mistakenly believed that Miss Paulus came to Japan with Douglas MacArthur after the war for Lutheran missionary work. I was surprised to learn that she was, in fact, a dedicated female missionary who had first arrived in Japan during the Taisho era. I spent two years there, in nursery and kindergarten. My mother was close to the teachers, so I had the freedom to do as I pleased, which often led to me being locked in a Western-style barrel. When I looked up, the pattern on the ceiling seen through a small round opening felt eerie.

From the kindergarten garden, I could see a 180-degree view of the winding Edogawa River. Boats that made a thumping noise frequently traveled the river. Smoke rose from the factories in the industrial zones of downtown Tokyo, with Mount Fuji faintly visible in the distance.

The reason I've elaborated so much on my kindergarten days is that this place is the root of my visual origins. Even now, I can vividly recall that landscape.

I attended a local elementary school in Kounodai, which was a free-spirited country school. However, when I was in the lower grades, I would probably be diagnosed with ADHD today. I walked around the classroom during lessons and was violent, causing my mother to be called frequently. In second grade, I was enrolled in piano lessons to calm me down, but was kicked out within a month. I managed to continue with art classes and enjoyed traveling alone by bus to the neighboring town of Yagiri. Once, I drew a memorable picture of a steam locomotive and its coaches stopped at Ryogoku Station. I was praised for capturing the curvature of the locomotive's boiler.

In second grade, my house underwent its first expansion. We used sticks as swords, and with my younger brother and a few friends, ventured into the mountains. These "mountains" were actually the expansive fields of the Kokubun area, about a 20-minute walk away. We bit into ripe tomatoes. Fields of small watermelons stretched as far as the eye could see. We smashed about ten of them with our wooden swords, only to find they weren't ripe enough to eat.

My younger brother told my father about our mischief. Furious, my father instructed me to take him to the field to apologize. We walked about 20 minutes to the watermelon field that weekend and, by chance, encountered the owner. My father apologized, but the man was even more apologetic.

I always feared my father when I was young. He usually came home late and left for work around noon. He often returned in a hired car, usually with the Asahi newspaper flag on it, and once even in an American car. Back then, newspaper journalists had prestigious jobs. Fathers in general had an air of authority, not just in our house.

I can't recall which grade it was, but there was a TV drama called "Crime Reporter" on air. At the time, my father was a captain at the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department. To a struggling student like me, it seemed a dazzling career. To be honest, throughout my elementary years, I spent most of the time running away from my father. Summers were the toughest, as it meant more chances of running into him. Every morning, I'd wake up past 6 and head to my friend F's house about 20 minutes away by foot. I'd wake her up, and we'd play together. She was smart, athletic, mischievous, and beautiful. She was a reserved, quiet child, possibly a contrast to her noisy, chatty mother.

I was attached to her and probably had a soft spot for her. After graduating from high school, she worked at the New Japan Hotel in Akasaka, saved up some money, and then traveled to America on a cargo ship. There she met Mr. Paulus, who was about to retire, and assisted him.

I met her a few years ago when she had grown old. I hadn't seen her for over 50 years. The reason we met was due to a 50-year elementary school reunion. She wasn't able to attend but had given her home phone number. I insisted on meeting even though she was initially hesitant.

She had hopped from one job to another, but was now, at the age of 70, working as a taxi driver. Not out of necessity, but because she liked driving. She still drives around Tokyo, going wherever she pleases. When I asked her what she thought of the young boy who used to barge into her house every morning, she said I was quite a handful, pulling her hair and even biting her. She had no recollection of this. Her mother advised her to be kind to such children. Hearing this, my youthful affection for her crumbled.

She mentioned that her life always seemed to be for others. I heard about her marriages and relationships, and they all seemed to center around taking care of someone else. Currently, she looks after her 104-year-old and 99-year-old parents. "Maybe that's my destiny," she mused. Perhaps that's why she became a taxi driver, to do something for herself.

In the third grade, my teacher, Mr. HORIKIRI, was especially kind to me. His father was a famous educator who served as the principal of several schools. Every holiday, I visited Mr. HORIKIRI's home. Once, during a typhoon, his home in Ichikawa town was flooded. Even then, I visited. He was a special teacher to me.

Around that time, my emotions began to settle. It was customary to play outside until dark after school. While I never studied, I had a deep fondness for science books and magazines. Even without studying, I excelled in science and Japanese language subjects. In the heyday of the abacus schools, half of my class attended them. I couldn't fathom sitting down and doing the abacus. Mori, a son of someone from the abacus school, always made mental calculations look easy, which further diminished my interest. My love for science was undeniable, but my aversion to math led me to the arts.

My mother was born in Sukagawa, Fukushima. She's currently 101 and still going strong. Her family ran a pharmacy, and it seems they even sold photographic solutions in the past. They also enjoyed photography. My grandfather passed away from cancer when I was just an infant. After graduating from Asaka Women's School, she worked in a bank and met my father, a returnee from the Shanghai Incident, through mutual friends. She had always wanted to go to college but couldn't due to her many siblings. During the war, she moved to Tokyo and worked at the "Literature for the Nation Association," meeting numerous writers.

My youthful father was supportive of my mother's university aspirations. The rarity of such supportive men at that time was the reason for their union. She pursued her studies in the Department of Literature at Nihon University's College of Arts. Growing up, our house was always filled with literary collections and various books. Visitors would often think the books were my father's, but they all belonged to my mother.

My maternal grandfather was a politician who served as the chairman of the prefectural assembly. My mother, the second of eight siblings, loved studying. Her older sister was beautiful and got married early. She had a child soon after, but it's said that he was conscripted and died in battle in Vietnam during the Pacific War, leaving her a war widow.

Despite our family's circumstances, my mother didn't pressure me to focus on my education. Our home was filled with life magazines, and we had tableware from Jiyu Gakuen. We had everything a child could want to play with. She simply wished her mischievous and rowdy son would turn out to be a good kid like the others. She never told me to study.

In the fifth grade, perhaps because of my good voice, on the recommendation of my teacher, Mr. Fujiwara, I was forced to join the choir club, which mainly consisted of girls. There were only three of us boys, one of whom was Mori from an abacus tutorial school. Although I didn't dislike singing, I often had to sing the harmony parts, not the main melody. Songs like "Haru Kouro no Hana no En" were dull to me. After the choral competitions, the three of us boys would often skip club activities. Since Mori lived nearby, we became close friends, walking to school together every day.

On my 9th birthday, just before entering the fourth grade, my father bought me a starter camera. I took pictures around our house and when we went to Mount Tsukuba. The neighboring Segawa Photo Store owner sometimes printed them for me, saying they were well taken.

The next year, for my 10th birthday, I received a children's camera, the popular Fujipet. 120 film was expensive, so I only took a few pictures of my surroundings and friends. There's still a picture in my album of me taken at a bakery, standing between a 2000 yen cake during Christmas. Regrettably, even though I had organized them properly, I lost the negatives.

Life in elementary school settled down quite a bit. Even though Ichikawa City was a region with a high emphasis on education, Kokufudai Elementary, located in the more rural part of the area, had a rather pastoral atmosphere. On sunny days, lessons would spontaneously change into outdoor activities like climbing the nearby Sankei Mountain.

In the comments section of my fifth-grade report card, where phrases like "Restless", "Noisy", and "Uncooperative" used to appear, there suddenly was, "I'm surprised by your popularity." My mother was taken aback too. Following a class poll on who everyone wanted to sit next to, I, once the troublemaker, had suddenly become the most popular.

In middle school, I had intended to go to a local school, but my father decided on a public middle school in Tokyo. The district aimed for the prestigious Metropolitan Hibiya High School. I ended up attending Chiyoda Municipal Nari-nari Middle School through a cross-district commute. Up to that point, I had never studied seriously, so middle school life was hellish. Though I wasn't slow, I somehow always ended up at the bottom of the class. I couldn't showcase my strength in long-distance running as there weren't tests for it. Maybe my athletic abilities declined because I grew so rapidly, or perhaps it was psychological. I was 150 cm tall when I entered middle school. Though I was taller than most during my early primary years, my height growth stalled. Consequently, many girls outgrew me.

Unbeknownst to me, my voice changed, and my height shot up; by the time I entered high school, I was 174 cm tall. I continued to grow, ultimately stopping at 179 cm.

My personality shifted from being a cheerful kid during my primary school days to becoming sensitive in middle school. I admired a girl in the wind instrument club who played the flute, but I lacked the courage to join. Unexpectedly, I found myself reading books in the library, mainly ones about natural science.

At that time, the top high school was Metropolitan Hibiya High School, renowned for its high University of Tokyo entrance rate. The top students all aimed for it, a world completely unrelated to me. In the end, I couldn't get into a metropolitan school and went to a private high school.

Nihon University Toyoyama High School was an all-boys school where everyone had a buzz-cut. The school was famous for its swimming team and brass band. There, I took on the flute, which I had admired. Once, at a kiosk in Akihabara station, I bought a book titled "Vanishing on the Alps," which told the tragic tale of a young flutist couple on the verge of worldwide acclaim. Embracing the profound impact of the story, I attended a concert by the famous flutist, Rampal, at the Ueno Cultural Hall. There, I ordered an LP record of the tragic Kato Hirohiko and played it to the point of wearing it out.

Back then, our high school brass band primarily performed marching music, notably compositions by Philip Sousa. Our performances were mostly in tandem with the cheer squad. Playing marches was often dull for flutists, so I decided to delve into classical music and took private flute lessons in Mitaka. Through these lessons, I realized the rigor of classical music. One day, while waiting for my lesson, a young boy played the flute phenomenally well, leaving me in shock. Had I encountered folk or rock music, which was popular back then, perhaps a different world would've opened up for me. Music was something I revered above all other forms of art.

One time, a classmate invited me to a church in Ochanomizu. I had encountered Christianity during my kindergarten years, so it felt familiar. Though the church was a strict Protestant denomination, I was jokingly considering baptism. My mother wasn't pleased when I mentioned it. During my last summer in high school, my Japanese language teacher, Tobana-sensei, assigned Somerset Maugham's "The Moon and Sixpence" for reading. The first half was tedious, but during the last week of the break, I became engrossed and finished it overnight. After completing it, I had an epiphany and felt as if another version of me was watching from above. That's when I decided to pursue a career in the arts. While I wanted to become a musician, I didn't have the environment for it and quickly gave up.

Around that time, I didn't consider photography to be art, but I recognized it as a form of expression. My father was a newspaper journalist, so I was familiar with the idea of photojournalism. However, since I despised studying, becoming a newspaper journalist was out of the question. The photographers I knew were Domon Ken and Robert Capa. My father recommended Domon's "A Bit Out of Focus," which I found entertaining like a novel, but it lacked realism. Little did I know that I'd eventually write a non-fiction book in 2004 titled "Robert Capa's Last Days," exploring Vietnam, where Capa met his end.

In March 1967, my cousin Ritsuko from my mother's hometown, Sukagawa in Fukushima, visited. My younger brother, Kenji, and I took her to Tokyo Tower. I had been there once before with my family soon after its completion in 1958. Back then, there were statues of the Eskimo dogs Taro and Jiro. In one corner of Tokyo Tower, they were offering computerized career predictions. I was excited to see what it'd suggest for me, now set on photography. To my surprise, the ideal job it suggested was "Commercial Photographer." I was happy about the "Photographer" part but wished it had specified "Photojournalist." Had it done so, I might've dashed straight into that career.

In 1967, I enrolled in the Photography Department of Nihon University's College of Art. I quickly abandoned the idea of becoming a photojournalist as the era was more attuned to advertising, fashion, and art photography. Photographers from the generation a decade older than me shone brightly; it was indeed a time when photographers held significant influence.

Kishin Shinoyama, Yoshihiro Tatsuki, Hajime Sawawatari, Noriaki Yokosuka, Shunji Okura, Kazumi Kurigami, Noriaki Kano, Umihiko Konishi, Akira Sato, Ikko Narahara, Yutaka Takanashi, Taiji Arita, Masayoshi Sukita, Shome Tomatsu,Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Eiko Hosoe, Hiroo Kikai, Daido Moriyama, Shin Yanagisawa, Kazumasa Suda, Masahisa Fukase, Katsumi Watanabe, Masatoshi Naito, Ken Ohara, Takuma Nakahira, Nobuyoshi Araki... and I think there were more. Did I miss anyone?

From my student days, I was curious about Hideki Hosoya and Kiyoshi Tatsukawa, who were active in the fashion magazine "Ryuko Tsushin." As for compositional photography (Konpora-shashin), Naotoku Tanaka, Shigeo Ushigushi, Tadaaki Enomoto, and Akihide Tamura were famous. Later on, Yoshinobu Jumonji and Tohru Kogure gained prominence.

When I entered university, I was most influenced by a classmate who was in the same club as me, Matsutoshi Takagi, who would later become the chief of the photography division at the Japan Design Center. The first time I saw his photos, I realized that there were images more interesting than those taken by photojournalists.

Even if snap photography is considered "Straight Photography," I realized it wasn't journalism. And so, while I was influenced by the trending compositional photography, I was also drawn to photos like those of Matsutoshi Takagi, which somewhat reminded me of Harry Callahan's style.

I learned that photography is not so much about capturing the truth, but more about crafting beautiful lies.

In the spring of my sophomore year in college, anti-Vietnam War movements flared up worldwide, and student power exploded. It was June 19th, 1968, a strangely atmospheric clear afternoon. As if on cue, students began hauling desks and chairs out of classrooms, barricading the university. I was among them. Suddenly, there was an executive body in place which ordered us, the soldiers, to keep watch by the main gate of the piled-up barricades in 3-hour shifts throughout the night, each of us carrying a whistle. The Arts Department at Nihon University was more focused on democratizing the school than on the anti-Vietnam sentiment. Still, this executive body somehow became authoritative, ironically turning things on their head. Yet amidst this, there was a dedicated food supply team of girls, and the atmosphere felt like an exhilarating war game. At night, during general meetings in the small auditorium, a zealous squad leader, high on heroism, would shout, "Tonight, whether the riot police storm in or the right-wingers attack, we'll resist to the end!"

I remained barricaded until the beginning of August, participating in demonstrations and soliciting donations. Around the Obon festival, my father, sticking to his yearly summer vacation tradition, beckoned me to Tateyama in Chiba. After a week, sunburned to a crisp, I returned to the barricades. Classrooms, now hot in the height of summer without air conditioning, were almost empty, with just a few remaining. Without demos or solicitations to attend, I simply decided to leave the barricades. I oddly had no desire to take pictures.

In September, I attended a few demonstrations. On the 12th, I captured the mass negotiations at the Nihon University Auditorium in Ryogoku, and on the 30th, a protest in Kanda Surugadai and Jinbocho. Coincidentally, in one of my shots was Fusako Shigenobu, who would later become a top executive of the Japanese Red Army. At that time, she was an unknown activist of BUNT. Then, I documented the Shinjuku riot on October 21st. My enthusiasm for photographing demonstrations waned after capturing the meeting at the University of Tokyo's Yasuda Auditorium on November 30th. I merely watched the fall of the Yasuda Auditorium in January 1969 on television.

In December 1968, riot police surrounded the Arts Department, filling the streets with tear gas. During that time, I briefly locked eyes with war photographer Taizo Ichinose, holding his Nikon S. We shared a brief connection, but with our photography circle disbanded, neither of us greeted the other.

Ichinose was a senior member of our university circle, the PhotoPoem Research Association. Born in Takeo City, Saga Prefecture, he aimed to be a photojournalist and was an outsider within the circle. I visited his room during my freshman year, where he showed me his printing process. He had been a professional boxer and bartender in Shinjuku's 2-chome. After graduation, he traveled to Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Cambodia. Although he arrived late to cover the Vietnam War as a photojournalist, he submitted his works to magazines in Japan and the US. After November 11, 1973, he went missing and was never heard from again.

In February 1969, riot police stormed the Faculty of Arts in Ekoda, breaking the barricades. By May, two-thirds of the campus was dominated by towering steel barricades constructed by a construction company during the student protests, behind which a new school building was steadily rising. When the barricades were removed, there stood a Bauhaus-style building, a courtyard, and a glittering glass-walled cafeteria.

The entrance ceremony and the freshman welcome event were held in a pristine space with its main entrance firmly shut. Post-protest, the Faculty of Arts in Ekoda shone anew, emanating an oddly bright ambiance. The following year, "anan" magazine was launched. Initially, it was purely a fashion magazine. The outfits for photo shoots were custom-made. While the entrance ceremony for the freshmen was modest, reminiscent of high school, by 1970, many students were dressed in trendy maxi dresses and pants, looking as if they jumped out from fashion magazines.

Due to the student protests, there was a year's hiatus. We had to cover two to three years of study in one. Tests and assignments were considerably simplified during this period. This was a boon for the photography department of Nihon University, known for its heavy workload, giving students like me ample time to shoot personal projects – a practice akin to contemporary photography.

By the time 1970 rolled around, thoughts turned to employment. Serious students had already started part-time jobs at advertising agencies or production companies by their second or third year. Job postings at the student affairs office were scant. Photography was a popular profession, but vacancies were almost nonexistent. Nearly all young renowned photographers were freelancers. Unless it was a top-tier position, becoming an assistant was a faster route. During the era of color positive film, mastering professional film required training. You either had to be affiliated somewhere or work as an assistant, given that one only truly learned by using large amounts of film.

One day in my third year, my father suggested I work for Asahi. Even though I had declared I wouldn't become a photojournalist, he introduced me to photo department heads and editors at Asahi Camera. They unanimously advised of the challenges of being a freelance photographer.

After graduation, I worked part-time in the darkroom at the Japan Design Center. Concurrent with my graduation, I was heartbroken, being suddenly dumped by my girlfriend of two years on the coast of Chigasaki. But when down, I took many photographs. The more despondent I felt, the better my photos turned out. The photography magazine "Camera Mainichi" had a public submission section called "Album". One summer, I took my works to meet Mr. Shoichi Yamagishi of Camera Mainichi, then referred to as the "Emperor of the Photography World", in hopes of being featured. Luckily, I met him directly. I was nervous. He casually flipped through my photographs, praising them. When I asked if they would be featured, he said the decision would be made in an editorial meeting. I had assumed his praise meant approval. Seeing my discontent, he showed me a draft of an upcoming issue featuring works by Ken Obara, and reassuringly patted my shoulder, implying the complex nature of decisions. Ultimately, my works were featured in the February 1972 issue. At that time, Mr. Yamagishi was neither an editor-in-chief nor a desk editor, just a regular editor.

I later learned from Mr. Suken Kanazawa, who interpreted for Robert Capa during his visit to Japan, that during the two revolutionary years when Mr. Yamagishi made his mark, the actual editor-in-chief was Mr. Kanazawa himself. When he became editor-in-chief, he was seemingly unenthusiastic about the role. The reasons are elaborated in his book. Handing photography tasks to the promising young Yamagishi and machinery-related tasks to Kakutaro Saeki, Kanazawa would often head to Ginza for evening drinks, only attending to the wrap-ups.

In the autumn of 1971, I was introduced to Mr. Kishin Shinoyama, the number one photographer at the time. He mentioned that he was reducing his workload, but he was still not letting go of the two assistants he had. He told me that if I was prepared to wait two or three years, he might hire me next. At that time, I was taking my own photographs, so I thought I was incredibly lucky. I wasn't sure if my photos would be published daily, but Masaji Yamagishi praised my work, which boosted my confidence. I felt I could now take my time and focus on my photography.

However, in December, Shinoyama's office told me to join them from the following January. This sudden request was because Noboru Takahashi, an assistant who had been photographing the "Oh-pa" of Kaikoh Ken, had gotten injured in a traffic accident. Though I had ongoing photographic assignments, the opportunity to become Shinoyama's assistant was clearly the priority. Shinoyama was working on a project photographing sumo wrestling for the monthly magazine "Sun." Every day, he went to the Kuramae Kokugikan for shoots, and all the development and printing were diligently handled by his second assistant, Yoshiyuki Miyagitani, who worked tirelessly. I assisted him, primarily handling the drum drying process. A few times, Bishin Jumonji, who had just become independent the previous year, came to use the darkroom.

In April 1971, before joining Shinoyama, I had wanted to become an assistant photographer after graduation but ended up working at the Japan Design Center. There was no vacancy for a shooting assistant, so I became a darkroom assistant. Daily, I was tasked with drum drying, which gave photographs a glossy finish, a technique that became obsolete in the 1980s with the advent of RC paper. Drum drying was a meticulous process at the time. I was sleepy but managed to get through it thanks to my experience at the Design Center.

Shinoyama worked as if he were a celebrity. There, I learned the work methods of Japan's top photographer. Technically, he was unmatched amongst Japanese photographers of that era. However, when I went independent, the way he approached his work didn't help me at all. In fact, my encounter with Shinoyama deconstructed my approach to photography. I wouldn't realize this until around 1985.

By the summer of 1972, Noboru Takahashi had returned from his injury, making us a team of three. Originally, Takahashi was the primary assistant and Miyagiya was the second. But since I learned everything from Miyagitani, my loyalty was with him, not Takahashi, which led to a somewhat stressful dynamic among the three of us.

At the end of 1972 and into the New Year of 1973, I alone accompanied Shinoyama on a photoshoot in Hawaii. It was my first time in Hawaii, and I remember being excited by the views from the car as we traveled from the airport to Waikiki. There were hardly any Japanese tourists; most Asians I saw were of Japanese descent. I was surprised by how robust and fit they looked. We had lunch at the Kahala Hilton Hotel, which was filled with wealthy tourists who looked like they could be in a Hollywood movie.

Being Shinoyama's assistant was demanding, but there were many overseas assignments, and only one assistant typically accompanied him on these trips. The other two assistants left behind had some free time. I was restless and eager to shoot, so I took snapshots every Sunday. I also photographed racetrack enthusiasts in places like Shonan and the Ebina Service Area at night, using my junior colleagues from university as assistants.

I had initially planned to leave after two years, but my seniors didn't quit. First Miyagitani, and after the oil crisis, Takahashi went independent. But when I became the chief assistant, my second, Mr. Miyaguchi, quit before me. He was the son of a famous actor and had married a foreign woman. When their baby was born and given that she earned more, Miyaguchi decided to become a homemaker. One day, Shinoyama asked me to stay another year. I ended up working with him for three years and eight months and was 26 when I left.

At that age, I felt a bit impatient. I would have preferred to wander or take some time off, but seeing the success of Takahiro Sugihara, who had previously been an assistant to another renowned photographer, Saku Sawada, made me feel more pressured. Another significant advantage of being Shinoyama's assistant was that both his and Sawada's offices were in the same building in Roppongi, with a shared darkroom and assistant room. In a way, it felt like being an assistant to both photographers.

When I went independent, I rented an office-cum-residence in Aoyama. It was located in a building owned by a developer named ASK. It didn't have a bath, but I was close to a public bathhouse. Answering machines had just become popular, and I promptly got one. I hired a full-time assistant and set up a small darkroom. My very first occasional assistant was Akira Gomi, who was still a photography student at Nihon University.

My first job after going freelance was the cover for the 1st anniversary of Monthly Playboy. Art director Mr. Tanami approached me to photograph a neon sign of a bunny on the coast of Shizuoka and in a theater. The second job was a 7-page lead gravure for Kodansha's Shonen Magazine, where I photographed newly debuted actress, Kimiko Ikegami, at the Akita Kakunodate festival. I asked the up-and-coming lyricist, Takashi Matsumoto, to write the accompanying copy (poem). It was well-received, and as a follow-up, I photographed the newcomer, Hiromi Iwasaki. The copy (poem) was by Yumi Arai, with whom I had ties since her first album "Hikouki Gumo". Later, I photographed acts like Candies and Takao Kisugi. However, I caused various issues and was disliked by the then-editor-in-chief, resulting in about a year without work. During that time, I worked for magazines like Monthly Playboy, Weekly Playboy, and Weekly Post. I met producer Mr. Teruo Iwata there and did many projects with him. About a year later, being stuck with just male-oriented magazines, I, then a young photographer, started pitching to popular fashion magazines that I wanted to work with. Shooting for fashion magazines led to features in Monthly Commercial Photo, which in turn led to advertising jobs. While fashion magazine fees were low, advertising paid substantially more. In 1977, under the direction of Mr. Tadanori Yokoo, I photographed Sayoko Yamaguchi for a kimono calendar, which led to even more work.

I got married for the first time in 1977 and rented a house in Shimokitazawa. Before my divorce in 1981, I rented a one-room office in Daikanyama Pacific Mansion. It was a hotel-like building used by many photographers as their office. It was small, but I converted the bathroom into a darkroom. In the 1980s, I moved to a two-bedroom place with a much larger darkroom. From when I went independent to around 1985, I did all kinds of work. Initially, I worked a lot with talent, but after being featured in Commercial Photo and shooting fashion for Ryuko Tsushin, my advertising work surged.

Asahi Camera "Message from the Heart" 10p Model ANJU RENA "FREE" HEIBONSHA Publishers YMO candid photos. StudioVoice, Ryuko Tsushin, Monthly PLAYBOY I regularly worked on album covers, live pamphlets, and posters for Yumi Matsutoya and Kenji Sawada. For advertisements, I frequently photographed individuals for brands like Kose Cosmetics, Shiseido, Kao, and others like Japan National Railways, later JR, NEC, HONDA, MAZDA Eunos, KODAK, FUJI, Canon, RICOH, CONTAX, MINOLTA, Maybelline, Bridgestone Sports, De Beers, Banking Association, Fuji Bank, NEC, Kyoho, SUTRY, CAMPARI, JR Kyushu, JR Shikoku, and JR East Japan.

In 1985, I got married for the second time. Around that time, Gallery MIN opened in Meguro Ward's Himonya, located behind Daiei. The first floor served as a studio, with the basement also converted into a studio space. MIN, the owner, and my wife were friends. The gallery regularly hosted exhibitions of works by "New Color" photographers, with the artists often being invited. I wasn’t quite sure about MIN, who was a person of wealth. At that time, I wasn’t particularly interested in photography as an art form, but I would usually show up for opening parties.

From this period, especially among young Japanese photographers, negative color film became the choice over positive film, which captured too much detail. The ambiguity of negative prints was more appealing. Unlike positive prints which required professional experience, one could self-learn with negatives. Most sent their films for external processing but chose to print the color photos themselves.

Just like black and white photography, printing photos oneself brought out individuality and could be considered an art piece. There was a sense of satisfaction in creating a work. The recognition of "New Color" as an art form can be attributed to these photographers standing by their works. For them, the art piece was the print. They'd photograph the print with a plate camera for printing.

The rise of professional photographers using color prints led to improved printing technology. The era preferred color prints over sharp positives, especially for fashion and portraits, as they provided more natural depictions of skin. Cameras like Hasselblad and Rollei ensured atmospheric photos.

In 1985, I held my first solo exhibition, "THE DAY BY DAY - Every Special Day," at the Nikon Salon in Shinjuku Keio Plaza. Jun Miki, a renowned photographer, reviewed my works. I was summoned to the president's room at the Nikko Club in Marunouchi. Initially, I felt overwhelmed, but he ended up even suggesting the title for me.

Subsequent exhibitions included "Someday in Shanghai" at Studio Ebisu Gallery in 1986, and "American Heads" at the Nikon Salon in Shinjuku that same year. By the late '80s, I started the "TWILIGHT TWIST" series using flashlight techniques. During a Mazda advertisement shoot in 1987, I experimented with capturing humans using nighttime photography. This method was introduced in Asahi Camera as "Twilight Twist" in 1989, and I later used it for Shiseido's "Hanatsubaki" and other commercial and celebrity shoots.

I continued this series even after switching to digital photography. The 1990s saw me capturing many celebrities for photobooks. I regularly shot covers and gravure for a men's magazine called Scholar. While I didn’t have many fashion gigs, I had regular advertising assignments. In 1999, I started the "Girls in Motion" series in the car magazine NAVI, featuring interviews with young unknown women paired with a landscape and a bust-up shot.

I began using computers in 1991, with my first being an Apple Macintosh II FX. It cost 1.8 million yen for the base unit, and an additional 200,000 yen for a disk writer. It was one of the fastest machines at that time, but with just 4MB RAM and a 20MB hard disk, it required a further 6 million yen to be fully utilized. Not really understanding its capabilities, I acquired it, probably because of a lease offer. It remained more of an expensive toy for me. Maybe it was Japan's bubble era that had numbed my financial judgment. I mostly used the machine for games, word processing, making maps, and tinkering with HyperCard.

I visited Vietnam for the first time in October 1994. At that time, there were no direct flights from Japan, so I had to travel via Hong Kong. The US sanctions had been lifted, and it was announced that by the end of the year, JAL would have direct flights from Kansai Airport. Vietnam holds a special place for people of my generation. It's the country that fought against the US and won. People all over the world protested the Vietnam War. Aside from the US, the country's name I probably uttered the most was "Vietnam."

After its victory, socialist Vietnam became isolated from the world, much like North Korea is today. Once hailed as the "Pearl of the Orient," when asked on the last episode of the long-running Japanese travel show "Kaoru Kanetaka's World Journey" which city she would like to visit next, Ms. Kaoru Kanetaka responded with "Saigon." "Saigon?" By that time, the city's name had changed to Ho Chi Minh City due to its isolation from the rest of the world, but many still referred to it as Saigon.

Back then, when one mentioned Vietnam, images of Agent Orange, the effects of the war, the devastated cities, and economic collapse came to mind. Perhaps because it was a time when one couldn't enter Saigon due to its isolation, her mention of "Saigon" left a lasting impression on me.

By 1994, it was finally possible to freely enter Vietnam. I wanted to see for myself how the "Pearl of the Orient" had been destroyed and how impoverished it had become. These were my negative preconceptions.

However, upon visiting Vietnam and Saigon, I realized it was not a place of poverty and misery. It was a peaceful, vibrant, and abundant city. The markets were overflowing with grains, vegetables, fish, meat, and miscellaneous goods. I was told that it had been just as abundant even during the Vietnam War.

The true poverty came after Vietnam's victory over the US and its subsequent isolation from the world, when goods disappeared from the Bentai market.

In October 1994, I visited Vietnam for the first time. There were no direct flights from Japan then; I had to transit through Hong Kong. The U.S. sanctions on Vietnam had just been lifted, and I'd heard that by year's end, Japan Airlines (JAL) would operate direct flights from Kansai International Airport to Vietnam. For my generation, Vietnam holds a special place in our hearts—it's the nation that fought against and triumphed over America. People around the world shouted in protest against the Vietnam War. Apart from America, the country I mentioned the most was "Vietnam".

After its victory, socialist Vietnam became isolated from the rest of the world, similar to what we see with North Korea today. Once known as the "Pearl of the Orient", Vietnam piqued the interest of M.S. Kaoru Kanetaka, the host of a famous Japanese travel show. When asked which city she'd like to visit, she named "Saigon". Although the city had by then been renamed Ho Chi Minh City, many still refer to it as Saigon.

Back then, words associated with Vietnam were Agent Orange, destruction, and economic downfall. Yet, when I visited Vietnam in 1994, I did not find it to be a place of destitution and misery. On the contrary, it was bustling, with markets overflowing with produce, a sight that was said to be unchanged even during the Vietnam War. It was only after their triumph against the U.S. and subsequent global isolation that scarcity took root.

In that first visit in October 1994, I serendipitously captured a photo of a woman gracefully crossing the street in her Ao Dai, a sight that would become emblematic of my journey. Who was she? By spring 1995, my connection to Vietnam deepened when I met a Japanese interpreter of my generation, Do Quoc Trung.

1995 also marked the year of the Great Hanshin Earthquake. On January 17th, a Tuesday, I was in my villa in Izu. I didn't know about the quake until I heard it on the radio during my drive back. Unable to reach my friends in Kansai, I decided to visit Kobe, the epicenter, along with the novelist YAHAGI and my assistant. The highways were eerily empty, and unsure of how far we could go, we purchased mountain bikes, expecting to abandon the car at some point. My car, equipped with the bikes and press stickers, looked quite convincing, allowing us to pass through multiple checkpoints and eventually reach the collapsed Hanshin Expressway on the morning of January 23rd.

As I set up my large 4x5 camera to capture the wreckage, an NHK news crew began their live broadcast behind me. I felt out of place, setting up my equipment as if shooting a landscape. I decided to approach this tragedy as a landscape photographer instead of a photojournalist, though I grappled with a sense of guilt for perhaps being too self-indulgent.

My photos, published in a monochrome feature in a weekly magazine, were later used by art director Mizutani Koji in a poster campaign titled "Come Together for Kobe". The images were altered to reflect the human element behind the disaster, emphasizing that it wasn't merely a natural catastrophe but also a man-made one. The collapsed expressway section, built using a unique German construction method unheard of in Japan, was a testament to that. The controversial method was cheaper than the Japanese one and was a point of pride for the Kobe mayor, who had praised its cost-saving benefits. Shockingly, this section was dismantled within just a week of the earthquake. The poster won several accolades, cementing the lasting impact of that tragic event.

In 1995, I moved my office from Shibuya Daikanyama, which I had rented for nearly 20 years, to a standalone house in Meguro-ku Higashiyama. I was living alone since I divorced the previous year. It was a two-story house with 140 square meters. The second floor was a large, single room that resembled a showroom, which I used as a studio. One day, a salesperson from the Canon01 shop, from whom I had once bought an Apple Mac II fx, came to greet me. He mentioned that the latest PowerMac was a hundred times faster than the fx. Even if I equipped it with a scanner, printer, and MacBook, it would only cost around 1 million yen. This was when I began to seriously use a computer for work, incorporating Photoshop 5.0. Yet, I had no interest in digital cameras. Even though many designers and editors owned compact digital cameras, I viewed them as mere toys. Scanned photos taken with film cameras seemed far superior.

Digital data seemed more than adequate for on-screen viewing, but it wasn't yet viable for print production. The quality of analog photography was still noticeably better. In the end, I created mock-ups, scanned films, printed them using inkjet printers, and framed them for display.

In 1998, I decided to create a photo book from the photos I had taken in Vietnam over the previous four years. I made a high-quality digital sample and approached major publishers. But most publishers were hesitant to publish travel or snap photo books. Even though they were open to publishing photo books of celebrities, they believed photo books by photographers were not profitable ventures. The only commercially successful photo travel series at the time was "Paradise" by Kazuyoshi Miyoshi, published by Shogakukan. It wasn't a lavish photo book, but a light and affordable one. Miyoshi had been consistently publishing with this concept for about a decade. He was recognized as a true photo book artist. Although I was known for commercial shoots, men's and women's magazines, and fashion photography, I wasn't recognized as a photo book artist. I was told that photographers like me typically resort to self-publishing or buying the rights to their work.

Why were photos of celebrities, even unknown ones, publishable? At that time, there was a niche market of fans willing to buy nude photos. Popularity and appeal determined expected profits. They asked, "Do you, Yokogi, have fans?" Indeed, who would buy a pure photo book, especially one featuring snaps from Vietnam? Perhaps the major commercial publishers were not the right fit for such a project.

When I was feeling dejected, Kazuhide Miyamoto, the editor-in-chief of Shinchosha Photomuse, offered to publish my work. He suggested a 300-page book, with two-thirds being photos and one-third text. Up until then, I had never published a significant piece of writing, although I had written some. But I felt that I could write about Vietnam, especially since my first visit in 1994 was with novelist Toshihiko Yahagi. The following year, I was introduced to a Viet Cong interpreter by non-fiction writer Noriyuki Kanda. After that, I was always accompanied by writers when I traveled, such as an editor from the Weekly Bunshun magazine, Funakoshi. While they wrote articles, I took photos. We saw the same things, but I always felt something different. Working with them, I naturally started accumulating "words" within me.

I wrote most of "Afternoon in Saigon" in about a week. For the last chapter, "War Photographers Robert Capa and Taizo Ichinose", I felt a bit of research would be sufficient. I planned to contrast the quiet death of my college senior, Taizo Ichinose, with the famous war photographer Robert Capa, whose death was meticulously documented by LIFE reporter John Mecklin. While Ichinose died silently and unnoticed, Capa's death was a grand event marked by a funeral in Hanoi organized by General Corney. I knew Ichinose from college and through mutual connections, and had resources to write about him. Regarding Capa, a biography titled "Rober Capa" by Richard Whelan was popularly translated by author Kōtarō Sawaki, blending in his interpretations.

Driven by the details in the biography, I hoped to find a memorial for Capa in Vietnam, marking the place of his death. I headed to Taibin with my interpreter, Do Quoc Trung, to possibly pay respects. But when we arrived, we couldn't locate the mentioned places "Doai Tan" and "Tan Ne". Despite detailed records of Capa's death being on the embankment before the Tan Ne fortress, locals were unaware of such locations. Feeling lost, I had hoped that by referring to the exact location and time of his death, I could pay homage.

In 1998, Vietnam had strict rules preventing foreigners from conducting interviews without a journalist visa. Do Quoc Trung, a former public security officer, once told me that when local public security comes around, there's a huge commotion. So, he advised, "just pretend you're taking a taxi." In the end, we couldn't find out much, so we decided to take photos that resembled the last ones taken by Capa to make do. We planned to be better prepared next time.

By the end of 2003, I felt an increasing urgency due to time constraints. The next year, May 25, 2004, would mark the anniversary of Capa's death. I set aside all my other tasks and devoted my time to researching at the National Library. I examined newspapers and magazines from that era. In particular, detailed articles and photographs regarding Capa's stay in Japan could be found in Camera Mainichi, Mainichi Graph, and Mainichi Newspaper. By correlating the events, townscapes, weather, and photos taken by Capa, I was nearly able to determine his exact schedule within Japan.

For my research in Vietnam, I was introduced to the president of the Vietnam Photographers Association in Hanoi. As expected, nobody knew about Robert Capa, a cameraman from the enemy side, France. The president, who had studied photography in East Germany, knew of Capa but was unaware of his death in Vietnam. With the association's assistance, we began our interviews in March, starting from the potential sites of Capa's demise. Although I brought several photos as references, one picture taken on the morning of Capa's death had always struck me. It featured a person in a white Ao Dai with a parasol, whom I had always believed was a woman. However, our interpreter, Trung, pointed out that it was likely a distinguished elderly man. The photo had shadows stretching to the right, suggesting it was taken a bit after 7 am. Judging by the direction of the shadows, they were not heading east but southeast or south. Considering the orientation, Capa was not on the national road but on a different route, moving northward towards Thái Bình. During our investigation, we found out that there was a French military base and port in that vicinity.

With this route in mind, other photos taken by Capa started to make sense. Along this path, south of Thái Bình town, there were locations with similar sounding names. Although their current names differed, we could identify places like Doai Tan and Tan Ne. The specifics of this are described in the book "The Last Day of Robert Capa".

On May 25th, at the site where Capa had stepped on a landmine 50 years earlier, and where he took his last color and monochrome photos, a memorial ceremony was held. It was attended by Japanese residents in Vietnam, fans from Japan, members of the Vietnam Photographers Association, and local children. On the green paddy field path, a portrait of Capa was displayed. Without any prior arrangements, Vietnamese saxophonist Nguyen Van Minh played "Time Goes By", a song from the movie Casablanca. Interestingly, the lead actress of that film, Ingrid Bergman, famously had a relationship with Robert Capa. It felt as if this coincidence had summoned Bergman to this event.

The Era of Digital Cameras

The very first digital camera I touched was a 6-megapixel Leaf. It was for a shoot for a supplementary issue of Commercial Photo and for posting tests online, shot at the AY Studio in Setagaya's Ikejiri. We had everything brought over from PCs for this test shoot. We shot using a flashlight called "Twilight Twist" with a model. The original data is now lost, and only the small-sized photos I uploaded online remain. Had I the original, it would be of 35 full-size. The body used was a Hasselblad. I think the lens was a 50mm f4 Distagon.

The 2000s marked the dawn of digital cameras. I began with the Eos D30 and started using the APS-C, 6.3-megapixel Eos D60 in earnest before its launch in 2002. From the outset, I shot in JPEG. My method was to shoot in JPEG and adjust in PHOTOSHOP. Having been scanning positives into PHOTOSHOP for retouching since 1995, I felt that with 6.3 megapixels, digital finally matched film. While I still used film for medium format and 4x5, for 35mm I shifted entirely to digital. Initially, everyone used the 1-gigabyte microdrive that was rumored to be prone to failure, but I never faced any issues with it.

In 1999, after publishing the photo collection "Afternoon in Saigon" (Shinchosha), I released a Vietnam trilogy: the novel "Heat Eats, Naked Fruit" (Kodansha) in 2003, and the non-fiction "Robert Capa's Last Day" (Tokyo Book Publishing) in 2004.

In 2003, I appeared on NHK's "Ao Dai Renaissance," which aired on both NHK General and NHK BS.

In 2006, I published "Him on That Day, Her on That Day 1968-1975" (Ascom), a collection of snaps and portraits from my student days, through my time as an assistant, and up to my debut as a freelance photographer. This was accompanied by an exhibition at venues like the Blitz Gallery and Parco Gallery. All prints were made by scanning negatives and prints.

Around 2008, I contributed to numerous magazines and books, including Canon's series of advertisements for National Geographic, a book on Sigma DP1, and others on RICOH GXR and GR.

From the end of 2009, I took charge of both movie and stills for the TV Asahi, Canon-sponsored show "Traveling the World's Roads". It was the first program shot entirely with the video function of a DSLR camera. The video quality of the 5D Mark II was stunning. Most intriguing was the ability to use the 35mm full-size, still camera lenses as-is. I frequently used the TS24mm lens. Using a shift lens in videography is unique. I revisited several countries multiple times, so I must've shot in about 30 countries. For roughly 5 years, I was almost exclusively dedicated to this project.

Photography Exhibitions:

December 1985 - "DAY BY DAY" from Dec. 3-9 at Shinjuku Nikon Salon. 38 black and white photos. March 1986 - "Someday in Shanghai" from Mar. 27-Apr. 15 at Tokyo Designer's Space Photo Gallery & Studio Ebisu. 25 black and white photos. April 1986 - "AMERICAN HEADS" at Shinjuku Nikon Salon. 40 black and white photos. April 1993 - "TWILIGHT TWIST POLAROID" from Apr. 13-May 14 at Polaroid Gallery. 30 Polaroid 809 photos. March 1996 - "Vietnamese Women" at Hanae Mori Open Gallery. 12 digital photos. April 1996 - "TWILIGHT TWIST2" at Hanae Mori Open Gallery. 12 photos. May 1996 - "10000W NUDE" at Polaroid Gallery Toranomon. 40 Polaroid 8x10in photos. October 1998 - "The Wind Flows" at Polaroid Gallery Toranomon. 30 Polaroid Type 55 photos. March 10-July 25, 2003 - "Temporal Vietnam" at National Canon Salon. 12 digital prints size A0. May 28-July 21, 2003 - "Afternoon in Saigon 94 - 03" at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum. 106 Lambda crystal prints. November 13-December 25, 2003 - "Northwards, Northwards: Forgotten Vietnam" at Shinagawa Canon Tower. 10 digital prints size A0 and 50 prints size A3 Nob. September 2004 - "Robert Capa's Last Land" at Day's Photo Gallery. 20 digital prints. July 2005 - Group Exhibition "Summer Surf Tales" at Art Photo Site Gallery. 4 digital prints. January 2006 - "Teach Your Children 1967 - 1975" at Art Photo Site Gallery. 200 digital archival prints size A3 Nob and 10 size A1. March 2006 - "Teach Your Children 1967 - 1975" at Kyoto Gallery. 200 digital archival prints size A3 Nob and 10 size A1. May 2006 - "Shibuya Now and Then ~ DaydreamBeliever ~" at Shibuya Parco Logos Gallery. 66 digital archival prints 8x10in, color & black and white. December 1-13, 2006 - "TEACH YOUR CHILDREN 1967-1975 Those Days of Him, Those Days of Her" at Shibuya Parco LOGOS. January 19-March 3, 2007 - "TEACH YOUR CHILDREN 1967-1975 Those Days of Him, Those Days of Her" at Art Photo Site Gallery Nagoya. July 17-30, 2007 - "GX Traveler: Vietnam & Nippon" at Gallley Bauhaus. May 22-28, 2008 - "GLANCE OF LENS" at Portrait Gallery. 60 photos, color & black and white, digital archival prints. March 2011 - Photography Exhibition "Glance of Lens 2011" at BritzGallery. September 2011 - Photography Exhibition "GLANCE OF LENS 2011" at CANON Shinagawa Gallery S. 40 large prints. 2015 - Amazon CRP FOTO Project. Produced over 500 Kindle photo collections. October 2018 - ScrapsⅠ Photography Exhibition 1949-2018 at Bar Yamazaki Library. December 2019-January 2020 - ScrapsⅡ Photography Exhibition at Yamazaki Library. October 2019 - "Party" Photography Exhibition at PLAYS M Shinjuku. 40 black and white photos. 2019 - "Traveling the World's Roads" Photography Exhibition at Mitsukoshi Ginza. Direction and exhibit display. January 2020 - "Traveling the World's Roads" Photography Exhibition at Yokohama Information and Culture Center. Exhibit display. July 2022 - "Sawada Kenji x Hayakawa Takeji Photo Collection" priced at ¥27500. A third of the photos are by Yokogi Arayo. November 31, 2022 - "Julie Sawada Kenji Photography Exhibition" at Bar Yamazaki Library. 2023 - Photographed the kabuki actor, Ichikawa Somegoro, for 10 pages in the fashion magazine SPUR. May 2023 - "Catch it if you can ~ Time that can't be overtaken ~" at JPG Gallery.

INSTAGRAM 写真家 ALAO YOKOGI 横木安良夫(@alao_yokogi) • Instagram写真と動画

もしよろしければ 応援サポートお願いします。