WHOの国際保健規則: 新たに発表された草案の意図は変わらない

WHOの国際保健規則: 新たに発表された草案の意図は変わらない

ローダ・ウィルソン

2024年4月30日

投票予定日まで1カ月を切ったが、国際保健規則の改正案とパンデミック協定の草案はまだ交渉中である。 4月16日、改正国際保健規則(IHR)の新しい草案が発表された。

最新の草案では、これまでのいくつかの提案が明らかに覆されているが、これを理解する上で重要なのは、コビド19への対応が、現行の自主的なIHRの下で、アウトブレイクに対応するための新たなモデルを課すことに大きな成功を示したことを理解することである。製薬業界と強いつながりを持つ強力な民間財団が、この新たな対応を大きく方向づけたのである。

新たに発表された草案では、現行のIHRと同様に拘束力はないとされているが、それ以外の点では草案の意図は基本的に変わっていない。 その意図は、公衆衛生の管理をさらにWHOに一元化し、疾病発生への対応をワクチンなどの商品に基づいて行うことにある。

新IHRの変更は単なる化粧直し

デービッド・ベル、ティ・トゥイ・ヴァン・ディン著

世界保健機関(WHO)加盟194カ国とリヒテンシュタイン、バチカンで構成される2005年国際保健規則(IHR)締約国196カ国は、2年前からこの協定を更新するための改正案を提出し、議論してきた。1960年代に導入されたIHRは、各国の能力を強化し、保健上の緊急事態が発生した際の各国間の連携を向上させることを目的としている。国際法上の法的拘束力のある協定(すなわち条約)であるが、ほとんどの条項は常に任意であった。

IHR改正草案とそれに付随するパンデミック協定の草案は、いずれも5月下旬の世界保健総会(WHA)での投票を1ヵ月後に控え、まだ交渉中である。これらはともに、過去20年間の国際公衆衛生の大きな変化を反映している。WHOが以前から重視してきた、栄養、衛生、地域密着型医療の強化を通じて疾病に対する回復力を高めることではなく、WHOが公衆衛生政策をさらに一元管理し、疾病発生への対応を商品化されたアプローチに重点を置くことを目的としている。

[注:パンデミック条約は、パンデミック協定、パンデミック合意、WHO条約合意+(「WHO CA+」)とも呼ばれる。]

公衆衛生環境の変化

公衆衛生の変容は、WHOの資金調達がますます指示的な性格を強めていることと、その資金調達に民間部門の参加が増加していることに対応している。Gavi(ワクチン)やCEPI(パンデミック用ワクチン)を含む、コモディティ・ベースの官民パートナーシップの成長とともに、これは製薬会社と強いつながりを持つ強力な民間財団によって大きく方向づけられ、彼らは直接的な資金提供を通じて、また各国に直接もたらされる影響力を通じて、これらの組織の活動を形成してきた。

これはコビッド19への対応で特に顕著になったが、その際、WHOは事前のガイダンスを放棄し、大規模な職場閉鎖やワクチン接種の義務化など、より指示的で地域ぐるみの対策を優先した。その結果、WHOのスポンサーである民間や企業に富が集中し、国や住民の困窮と負債が増大した。どちらも、このようなアプローチの先例となり、世界はその押し付けに対してより脆弱になった。

新草案の意味するもの

最新の草案でIHRを改正するいくつかの提案が明らかに逆転していることを理解する上で、コビッド19への対応が、現在のIHRの任意的な性格の下で、この新しいアウトブレイク対応のパラダイムを押し付けることに大きな成功を示したことを理解することが重要である。製薬企業は、研究開発のための公的資金援助や無責任な事前購入契約など、非常に有利な契約を州と直接結ぶことに成功した。この契約は、メディア、保健、規制、政治部門への強力なスポンサーシップによって支えられ、高度なコンプライアンスと反対意見の抑圧の両方を可能にした。

法的拘束力のある協定のもとで、このビジネスアプローチを繰り返すために、WHOにより多くの規定的権限を集中させることは、将来的な繰り返しを単純化することになるが、すでに機能することが証明されているシステムに未知の要素を導入することにもなる。以前の草案のこうした側面は、国民の反発を招くことも明らかだった。製薬会社は、交渉の過程でこの現実を認識していた。

こうして4月16日に発表されたIHR改正の最新版では、パンデミックや国際的に懸念されるその他の公衆衛生上の緊急事態(「PHEIC」)を事務局長(「DG」)が宣言した場合、加盟国は将来、事務局長からの勧告に従うことを「約束する」という文言が削除された(旧新第13条A)。現在は「拘束力のない」勧告にとどまっている。

この変更は、WHO 憲章に合致し、各国代表団の行き過ぎに対する懸念を反映したものであり、妥当なものである。2022年の世界保健総会で場当たり的に可決された審査期間の短縮は、これを拒否した4カ国を除くすべての国に適用される。それ以外の点では、草案の意図も、それがどのように展開されるかも、基本的には変わっていない。世界銀行、IMF、G20は、全体的な計画が進むことを期待する姿勢を示しており、各国の負債が増加することで、これを強制する権限がさらに強まる。

WHOとそのパートナーは、付随するパンデミック協定とともに、自然ウイルスの亜種を特定するための大規模で高価なサーベイランスシステムを含む、(公衆衛生、公平性、人権の観点から)非常に危険な複合体を構築し続けている、 各国による迅速な通知、WHOによる希望する製薬メーカーへのサンプルの提供、通常の規制および安全性試験を回避した100日間のmRNAワクチン投与、そして集団接種に基づく対応。コビッド-19の反応に見られるように、集団予防接種に基づく反応は、正常な状態に戻す方法として売り込まれることになる。この反応は、実際の危害ではなく、単に脅威を認識したDGが単独で引き起こすことができる。製薬会社は公的資金によって支援されるが(パンデミック協定に関する議論を参照)、責任から保護された利益を受け取ることになる。

不適格で準備不足の文書

このシステムはWHOによって監督されるが、WHOは製薬会社から資金援助を受けており、パンデミック対策の主要な財政的受益者となる。WHOの総局長は、このプロセスを監督し、助言を与える委員会のメンバーを(最終的な責任者であるはずの加盟国ではなく)自ら選ぶ。WHOは、利益を得る立場にある同じ組織や民間投資家から、緊急課題のための資金援助を受けている。

このスキームにおける利益相反と腐敗の脆弱性は明らかである。国際的な官僚機構はすでにこのために設置されており、その唯一の存在理由は、ウイルス変異体や小規模な感染症発生、つまり自然現象である感染症が、特定の対応を必要とする脅威であると判断し、それを実行に移すことである。現総局は、サル痘の世界的緊急事態を宣言した。

最後に、後述する改正案は、完全なものとは言い難い。例えば、インフォームド・コンセントを必要とする条項がある一方で、奇妙なことに、そして憂慮すべきことに、これを無効にすることを推奨する条項があるなど、内部矛盾がある。パンデミックの定義は、病原体や病気そのものと同様に、その対応策に基づいている。審査期間の短縮をなくし、あからさまな強制力をなくすことで、緊急性と発生頻度に関する事前の誤った説明は認識されたようだ。

しかし、この文書とパンデミック協定案は、依然として5月末までに採決される予定である。これは、IHR(2005年)第55条で定められている法的要件を完全に反故にするものであり、この草案でも繰り返し述べられているように、投票前に4ヶ月の検討期間を設けている。これは、この文書の未完成という性質を考えれば不合理であるだけでなく、健康、人権、経済への影響を十分に評価する上で、資源の乏しい国々に不利になるため、不公平である。WHOが、草案が適切に検討された後に、WHAの投票を求めることを妨げる手続き上の理由はない。加盟国はこれを明確に要求すべきである。

重要な修正案とその意味するもの

現在の草案の主な変更点とその意味を以下に要約する。変更案はこちらをご覧ください。

この修正案は、緊急性がなく、負担が少なく、現在記録されている感染症アウトブレイクの頻度も減少していること、また、国際的・国内的な官僚機構や機関を新たに設置するために、すでに困窮と負債を抱えている国々に莫大な財政的負担を強いることを考慮して見直されるべきである。また、付随するパンデミック協定の草案、明らかな利益相反、コビッド19への対応中にWHOのスポンサーに富が集中したこと、コビッド19への対応とWHOが提案した新たなパンデミック対策について、透明で信頼できる費用便益分析が執拗に行われていないことを踏まえて評価されなければならない。

(本文注:以下の太字は、この草案で追加された新しい文章を示すため、改正草案での使用を反映したものである)

2024年4月28日

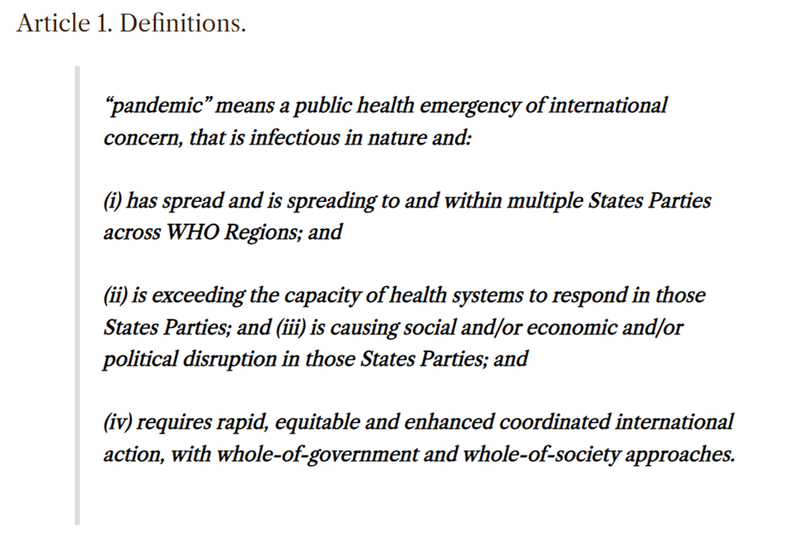

「パンデミック」の定義を草案に加えることは有益である。これなしでは、パンデミックのアジェンダ全体の定義がやや不明確であることは、最近、別の場所で指摘されたとおりである。「and」が使われていることに留意されたい。

しかし、これは技術的に欠陥のある定義である。(i)は常識的でオーソドックスな定義であるが、(ii)は国によって異なる。つまり、同じ流行がある国では「パンデミック」であっても、他の国では「パンデミック」ではないということである。また、社会的、経済的、政治的混乱を引き起こし、さらに "政府全体のアプローチ "を必要とするものでなければならない。

"政府全体のアプローチ "とは、定義不可能だが、公衆衛生ではよく使われる用語である。確かに、過去数世紀で感染症が発生した場合、ほとんどの政府の特定の部門だけが関与していたことは容易に確認できる。コビト19の際には、近隣諸国と同等かそれ以上の結果を達成しながらも、政府の方向転換は極めて限定的で、極めて軽いアプローチをとった国もあった。このことは、コビッド19が複数の国に「広がり、またその中で」病気を引き起こしたにもかかわらず、このパンデミックの定義から外れることを意味する。

この定義は十分に熟慮されていないように見えるが、これはこの文書の急ぎすぎの性格と、投票への準備不足を反映している。

「パンデミック緊急事態」は新しい用語である。この定義には、「または、そうなる可能性が高い」が含まれており、PHEIC の範囲を実際の危害を引き起こす事象ではなく、認識された脅威へと広げるために、「潜在的または実際的」を含んでいた前バージョンの第 12 条の変更に取って代わるものである。

「パンデミック緊急事態(Pandemic emergency)」は、「国際的に懸念される公衆衛生上の緊急事態(Public Health Emergency of International Concern: PHEIC)」のサブセットとして本文中で使用されているようである。これは、パンデミック協定がパンデミックに特化したものであるのに対して、IHRはいかなる種類の宣言された国際公衆衛生上の緊急事態にも対応するものであるため、将来的にパンデミック協定がPHEICに関する方針と合致するようにするためであろう。

前回の草案では、「......およびその他の保健技術(ただし、これに限定されるものではない)」という選択肢があり、「保健技術」を "well-being "を改善するものすべてと定義していた。

常設勧告と暫定勧告は、以前は削除されていた「拘束力のない」という文言が本文に戻され、「拘束力のない助言」に戻った(下記の第13条Aと第42条に関する注釈も参照)。

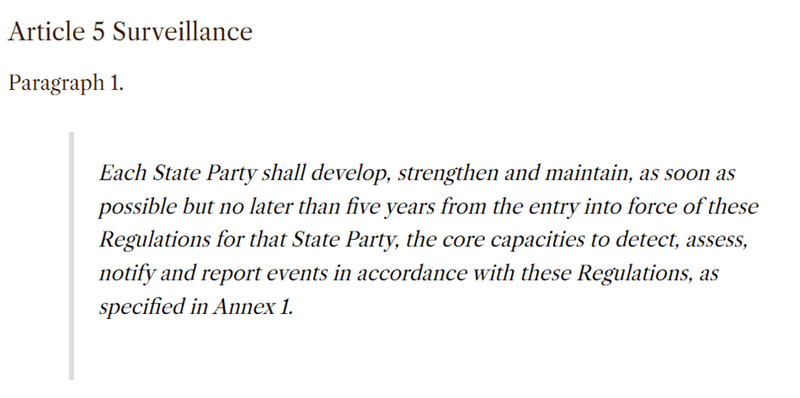

これは、特に低・中所得国にとっては依然として問題である。附属書1の「中核的能力」には、サーベイランス、検査室能力、専門スタッフの維持、検体管理が含まれる。多くの国々は、結核のような負担の大きい疾病について、これらの能力を開発し、維持することに依然として苦慮しており、この能力不足の結果、死亡率が高くなることはよく知られている。パンデミック協定では、このような資源集約的な要件をさらに詳しく説明している。低所得国は、高負担の健康問題から、平均寿命の長い裕福な欧米諸国が主要な脅威と認識している問題に資源を転用することで、重大な損害を被る危険性がある。

興味深いことに、「誤報や偽情報に対抗することを含むリスクコミュニケーション」という検閲への期待も、現在では附属書1にしまわれているが、基本的には変更されていない。

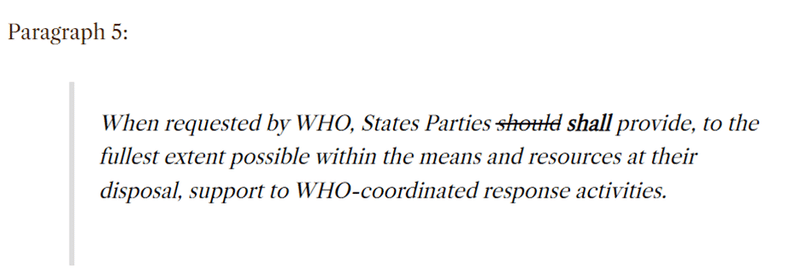

これが何を意味するかといえば、「すべき」から「しなければならない」への変更は、締約国が依然としてWHOから何らかの指示を受けることを期待されていることを暗示しているように思われる。これは主権問題への回帰であり、不遵守は金融メカニズム(世界銀行やIMFの金融商品など)を通じた強制執行の理由として使われる可能性がある。

この文言には「手段と資源の範囲内で」というエスケープ条項があるが、それではなぜ "should "を "shall "に変える必要があるのかという疑問が生じる。

PHEICまたはパンデミック緊急事態を宣言する権限は、DGのみが保持する(委員会に対するDGの権限に関 する下記第III章の規定参照)。

上記と同様、これは多くの状況において適切であるため、任意とする必要がある。これに続く代替(bis)バージョンの方がはるかに適切であり、衡平性に合致している:

事務局長は、PHEIC を宣言し、停止する唯一の権限を保持し、緊急時委員会と加盟国は助言のみを行う。

これは、国際的な旅行が経済に与える影響を通じて、コビッド19への対応で生じた損害に対する認識を反映したものであることが望まれる。低所得国では餓死者が出たり、観光が中止されると収入や将来の教育、特に女性を失うことになる。しかし、それは医療スタッフに限られているように見える。

ここで引用されている第31条第2項(下)は、実際には強制的なワクチン接種を支持しており、上記のインフォームド・コンセントの規定と衝突しているため、どちらか一方を書き換える必要がある(これが第31条であることを願っている)。

コビッド19への対応で悪用されたとはいえ、ワクチン接種の状況を国の主権的権利である入国の権利の基準として用いることは、ワクチンが当該国ですでに流行していない深刻な病気の感染を阻止する場合には、目的を果たすかもしれない。

すなわち、第23条とは逆に、インフォームド・コンセントは、加盟国が診察や注射を行うための要件とはならない。

入国時のワクチン接種は、渡航者における確立した感染を阻止することができないため、疾病の輸入を防止するためには何の役にも立たない。従って、入国時のワクチン接種の義務化は、人権上の懸念とは無関係に、正当な公衆衛生上の措置ではない。

健康診断の義務付けや、拒否された場合の隔離は、危険性の高い感染症における最後の手段として広く考えられるが、軽々しく課すべきではない。

これは、推進される対策によって利益を得る人々から直接資金援助を受けている組織の長としては、利益相反の観点から明らかに不適切である。締約国はWHOのオーナーとして、自国の専門家を提供すべきである。そうすることで、利害の衝突を減らし、多様性と代表性を確保することができる。

第47条の注釈を参照。

上記の通り、WHO総局は唯一の権限を有する。このことは、IHRの遵守を自発的なものにしておくことの重要性を強調している。現事務局長は、サル痘について国際的に懸念される公衆衛生上の緊急事態を宣言した。これによって、新しいパンデミック協定とその規定のもとで、事務局長は、隔離の勧告、迅速なワクチン開発、強制的なワクチン接種の推進、その結果としてのWHOのパンデミック・アジェンダの資金源となっている団体への利益供与といった一連のプロセスを開始することができるようになる。

上記の通りである。審査委員会が適切に機能するためには、独立した存在でなければならない。提案されたアプローチの私的受益者もプロセスのスポンサーであるため、対立が起こりやすいのである。

審査委員会としては、審査の対象となる人物の行動によって任命された者だけが投票権を持ち、決定を下すというのは異常なことである。しかし、ここにきてこのような事態が忍び込んでおり、加盟国による真剣な監視のための仕組みが提供されようとしていない。

WHOが自分自身を見直すというだけのことである:

この代替54条は、加盟国が実際の意思決定の役割を持つ委員会メンバーを指名することで、総局から監視を取り戻そうとする試みと思われる。もしそうであれば、文言の強化が有効かもしれない。

もちろん、これは2024年5月にこの改正案を採決することとはまったく相容れない。

意味合いを検討する時間はもちろん不可欠だ。そのためには4カ月では短く、4週間では馬鹿げている。

この条文は、2022年のWHA(2023年末までに否決された国を除く)でほとんどの国が受け入れた決議に基づいて修正され、検討期間が短縮される。このことは、DGからの報告書「27. 第75回世界保健総会(2022年)の決議WHA75.12で採択された規則第55条、第59条、第61条、第62条、第63条の改正は、2024年5月31日に発効する。すべての締約国に通知されたとおり、イラン・イスラム共和国、オランダ王国、ニュージーランドおよびスロバキアは、上記の改正を拒否する旨を事務局長に通知した。

新条約は投票から12カ月後に発効する(第63条)。

審査期間中に修正案を否決した4カ国には、旧版の条文が適用される。ただし、従来通り、それぞれ10カ月または18カ月以内に積極的な否決がなされなければ、法的拘束力のある条文が自動的に適用される(第61条)。

その他の問題

用語に関する一般的な注意。

「先進国」と「発展途上国」。WHOは、ある国が他の国よりも「先進国」であるという思い込みから、そろそろ脱却すべき時かもしれない。おそらく、世界銀行の慣習を反映した「高所得」、「中所得」、「低所得」の方が、植民地主義的でないだろう。先進国」は、進歩やテクノロジーが提供しうるものをすべて手に入れたのだろうか?

これはもちろん、20年前は「未開発」であり、文化や芸術、政治的成熟度、あるいは力の弱い国々に爆撃を加えないという嗜好ではなく、技術が唯一の発展の尺度であることを意味する。WHOは、インド、エジプト、エチオピア、マリなど、何千年もの文字による歴史と文明を持つ国々を "先進国 "ではないとみなしている。言葉は重要だ。この場合、言葉は、非常に唯物的な世界観に基づき、国(ひいては人々)の達成度や重要度におけるヒエラルキーの印象を助長する。

著者について

ブラウンストーン・インスティテュートの上級研究員であるデビッド・ベルは、公衆衛生医であり、グローバルヘルスにおけるバイオテクノロジー・コンサルタントでもある。元世界保健機関(WHO)医務官・科学者、スイス・ジュネーブの革新的新診断薬財団(FIND)マラリア・発熱性疾患プログラム責任者、米国ワシントン州ベルビューのインテレクチュアル・ベンチャーズ・グローバル・グッド・ファンド・グローバル・ヘルス・テクノロジーズ・ディレクター。

ティ・トゥイ・ヴァン・ディン博士(法学修士、博士)は、国連薬物犯罪事務所と人権高等弁務官事務所で国際法に携わる。その後、インテレクチュアル・ベンチャーズ・グローバル・グッド・ファンドで多国間組織のパートナーシップを管理し、低資源環境における環境保健技術開発を主導。

スペイン語訳:

Reglamento Sanitario Internacional de la OMS: La intención del nuevo proyecto no ha cambiado

POR RHODA WILSON

30 DE ABRIL DE 2024

A menos de un mes de la votación prevista, los cambios propuestos en el Reglamento Sanitario Internacional y el proyecto de Acuerdo sobre Pandemias siguen negociándose. El 16 de abril se publicó un nuevo borrador del Reglamento Sanitario Internacional ("RSI") modificado.

Para entender las aparentes reversiones de algunas propuestas anteriores en el último borrador, es importante comprender que la respuesta al covid-19 demostró un gran éxito al imponer un nuevo modelo para responder a los brotes bajo el actual RSI voluntario. Poderosas fundaciones de propiedad privada con fuertes conexiones con la industria farmacéutica dirigieron fuertemente esta nueva respuesta.

El nuevo borrador establece que no es vinculante, como lo es el RSI actual, pero por lo demás, la intención del borrador no ha cambiado. La intención es centralizar aún más el control de la salud pública dentro de la OMS y basar la respuesta a los brotes de enfermedades en productos básicos, como las vacunas.

Los nuevos cambios del RSI son meramente cosméticos

Por David Bell y Thi Thuy Van Dinh

Durante dos años, los 196 Estados Partes del Reglamento Sanitario Internacional ("RSI") de 2005 -integrados por 194 Estados miembros de la Organización Mundial de la Salud ("OMS"), y Liechtenstein y el Vaticano- han presentado y debatido propuestas de enmienda para actualizar este acuerdo. Introducido en la década de 1960, el RSI pretende reforzar las capacidades nacionales y mejorar la coordinación entre países en caso de emergencia sanitaria. Aunque se trata de un acuerdo jurídicamente vinculante con arreglo al Derecho internacional (es decir, un tratado), la mayoría de sus disposiciones siempre han sido voluntarias.

El proyecto de enmiendas al RSI y el proyecto de Acuerdo sobre Pandemias que lo acompaña siguen negociándose a un mes de la votación prevista en la Asamblea Mundial de la Salud ("AMS") a finales de mayo. En conjunto, reflejan un cambio radical en la salud pública internacional durante las dos últimas décadas. Pretenden centralizar aún más el control de la política de salud pública en el seno de la OMS y basar la respuesta a los brotes de enfermedades en un enfoque fuertemente mercantilizado, en lugar del énfasis previo de la OMS en la creación de resiliencia frente a las enfermedades mediante la nutrición, el saneamiento y el fortalecimiento de la atención sanitaria basada en la comunidad.

[Nota: El Tratado sobre Pandemias también se conoce como Acuerdo sobre Pandemias, Acuerdo sobre Pandemias y Acuerdo del Convenio de la OMS + ("CA+ de la OMS")].

El cambiante entorno de la salud pública

La metamorfosis de la salud pública responde al carácter cada vez más directivo de la financiación de la OMS y a la creciente participación del sector privado en dicha financiación. Junto con el crecimiento de las asociaciones público-privadas basadas en los productos básicos, como Gavi (para vacunas) y CEPI (vacunas para pandemias), esto ha sido dirigido en gran medida por poderosas fundaciones de propiedad privada con fuertes conexiones con Pharma, que dan forma al trabajo de estas organizaciones a través de la financiación directa y a través de la influencia ejercida directamente sobre los países.

Esto se hizo especialmente evidente durante la respuesta al covid-19, en la que se abandonaron las directrices previas de la OMS en favor de medidas más directivas y de ámbito comunitario, como el cierre masivo de lugares de trabajo y la vacunación obligatoria. La concentración de riqueza resultante entre los patrocinadores privados y corporativos de la OMS, y el creciente empobrecimiento y endeudamiento de los países y las poblaciones, sentaron un precedente para tales enfoques y dejaron al mundo más vulnerable a su imposición.

Implicaciones del nuevo borrador

Para entender los aparentes retrocesos de algunas propuestas de modificación del RSI en el último borrador, es importante comprender que la respuesta al covid-19 demostró un gran éxito en la imposición de este nuevo paradigma de respuesta a brotes bajo la actual naturaleza voluntaria del RSI. Las corporaciones farmacéuticas sellaron con éxito contratos altamente lucrativos directamente con los Estados, incluyendo financiación pública para investigación y desarrollo, y acuerdos de compra anticipada libres de responsabilidad. Esto se vio respaldado por un fuerte patrocinio de los medios de comunicación y de los sectores sanitario, regulador y político, lo que permitió tanto el alto nivel de cumplimiento como la represión de la disidencia.

Centralizar más poderes proscriptivos en la OMS para repetir este enfoque empresarial bajo un acuerdo jurídicamente vinculante simplificaría la repetición futura, pero también introduce un elemento de lo desconocido en un sistema que ya ha demostrado que funciona. Estos aspectos de los borradores anteriores también presentaban un foco obvio de oposición pública. La industria farmacéutica ha sido consciente de esta realidad durante el proceso de negociación.

Así, la última versión de las enmiendas al RSI, publicada el 16 de abril, elimina la redacción que implicaría que los Estados miembros se "comprometan" a seguir cualquier recomendación futura del Director General ("DG") cuando declare una pandemia u otra emergencia de salud pública de importancia internacional ("PHEIC") (antiguo nuevo artículo 13A). Ahora siguen siendo recomendaciones "no vinculantes".

Este cambio es sensato, se ajusta a la Constitución de la OMS y refleja la preocupación de las delegaciones de los países por la extralimitación. El plazo de revisión reducido que aprobó de forma bastante ad hoc la Asamblea Mundial de la Salud de 2022 se aplicará a todos los países que las rechazaron, excepto a cuatro. Por lo demás, la intención del borrador, y cómo es probable que se desarrolle, no ha cambiado en lo esencial. El Banco Mundial, el FMI y el G20 han señalado que esperan que el plan general siga adelante, y el creciente endeudamiento nacional aumenta aún más los poderes para coaccionarlo.

Se sigue esperando que los Estados gestionen las opiniones discrepantes, y junto con el Acuerdo sobre Pandemias que lo acompaña, la OMS y sus socios siguen estableciendo un complejo altamente peligroso (desde el punto de vista de la salud pública, la equidad y los derechos humanos) que implica un sistema de vigilancia masivo y costoso para identificar las variantes víricas naturales, un requisito de notificación rápida por parte de los países, el paso de muestras por parte de la OMS a los fabricantes farmacéuticos de su elección, la administración de una vacuna de ARNm en 100 días, eludiendo los ensayos normales de regulación y seguridad, y luego una respuesta basada en la vacunación masiva que, como se ha visto en la respuesta al covid-19, se presentará como una forma de volver a la normalidad. Esto todavía puede ser invocado sólo por el DG, simplemente en su percepción de una amenaza en lugar de un daño real. Las empresas farmacéuticas se financiarán con fondos públicos (véase el debate sobre el Acuerdo de Pandemia), pero recibirán beneficios protegidos por la responsabilidad civil.

Un documento inadecuado y poco preparado

Este sistema será supervisado por la OMS, a pesar de ser beneficiaria de la financiación de las farmacéuticas, que a su vez serán las principales beneficiarias financieras de la respuesta a la pandemia. El Director General selecciona personalmente a los miembros del comité que pueden asesorar y supervisar este proceso (en lugar de los Estados miembros, que se supone que en última instancia son los responsables). La OMS recibe financiación para su programa de emergencias de las mismas organizaciones e inversores privados que pueden beneficiarse.

Los conflictos de intereses y la vulnerabilidad a la corrupción son evidentes. Ya se está creando toda una burocracia internacional para ello, cuya única razón de ser es determinar que las variantes víricas y los brotes menores, parte natural de la existencia, son una amenaza que requiere una respuesta específica que luego deben aplicar. La actual DG declaró una emergencia mundial por la viruela del mono, tras sólo cinco muertes en un grupo demográfico claro y relativamente restringido.

Por último, el texto actual de las enmiendas que se comentan a continuación dista mucho de estar completo. Existen contradicciones internas, como cláusulas que exigen el consentimiento informado y, de forma extraña y alarmante, recomiendan que se anule. La definición de pandemia se basa tanto en la respuesta como en el agente patógeno o la enfermedad en sí. Al suprimir el periodo de revisión abreviado y eliminar la obligatoriedad manifiesta, parece haberse reconocido la tergiversación previa de la urgencia y la frecuencia de los brotes.

Sin embargo, este documento, y el borrador del Acuerdo sobre Pandemias, todavía pretenden ser votados antes de finales de mayo. Esto deroga completamente el requisito legal del Artículo 55 del RSI (2005), que se repite en este borrador, de un periodo de revisión de cuatro meses antes de cualquier votación. Esto no sólo es irracional, dada la naturaleza inacabada del texto, sino también injusto, ya que perjudica a los países con menos recursos a la hora de evaluar plenamente los posibles impactos sobre la salud, los derechos humanos y sus economías. No hay razones de procedimiento que impidan a la OMS solicitar una votación posterior en la AMS una vez que los borradores hayan sido debidamente revisados. Los Estados miembros deberían exigirlo claramente.

Enmiendas significativas propuestas y sus implicaciones

A continuación se resumen los principales cambios e implicaciones del actual borrador. Los cambios propuestos se encuentran AQUÍ.

Las enmiendas propuestas deben revisarse a la luz de la falta de urgencia, la baja carga y la frecuencia actualmente decreciente de los brotes de enfermedades infecciosas registrados, así como de las enormes necesidades financieras de los países -ya muy empobrecidos y endeudados tras los bloqueos- para crear burocracias e instituciones internacionales y nacionales adicionales. También debe evaluarse a la luz del proyecto de Acuerdo sobre la Pandemia que lo acompaña, los aparentes conflictos de intereses, la concentración de riqueza entre los patrocinadores de la OMS durante la respuesta al covid-19, y la persistente ausencia de un análisis transparente y creíble de la relación coste-beneficio de la respuesta al covid-19 y de las nuevas medidas pandémicas propuestas por la OMS.

(Nota textual: El texto en negrita a continuación refleja su uso en el borrador de enmiendas para denotar el nuevo texto añadido en este borrador).

Los nuevos cambios del RSI son meramente cosméticos, Brownstone Institute,

28 de abril de 2024

Es útil que se añada una definición de "pandemia" al borrador, ya que recientemente se ha señalado en otro lugar que sin esto toda la agenda pandémica es algo indefinible. Nótese el uso de "y"; todas estas condiciones deben cumplirse.

Sin embargo, se trata de una definición técnicamente defectuosa. Mientras que la cláusula (i) es sensata y ortodoxa, (ii) variará entre Estados, lo que significa que el mismo brote puede ser de alguna manera una "pandemia" en un país, pero no en el otro. También debe estar causando trastornos sociales, económicos o políticos, y además debe requerir un "enfoque de todo el gobierno."

"Enfoques de todo el gobierno" es un término indefinible pero popular en salud pública, que se puede argumentar que no es casi nada - ¿qué requiere realmente un enfoque de todo el gobierno? Ciertamente, ningún brote de enfermedad infecciosa de los últimos siglos lo confirmaría fácilmente, ya que sólo estaban implicados brazos específicos de la mayoría de los gobiernos. Algunos países adoptaron un enfoque bastante ligero durante el covid-19, con una reorientación gubernamental muy limitada, al tiempo que obtenían resultados similares o mejores que los estados vecinos. Esto significaría que covid-19 quedaría fuera de esta definición de pandemia a pesar de "propagarse a y dentro de" múltiples Estados, y también de causar enfermedades.

Esta definición no parece suficientemente meditada, lo que refleja el carácter apresurado de este documento y su falta de preparación para la votación.

"Emergencia pandémica" es un término nuevo. La definición incluye "o es probable que lo sea", sustituyendo así el cambio en el artículo 12 de la versión anterior que incluía "potencial o real" para ampliar el ámbito de aplicación de la PHEIC a una amenaza percibida en lugar de a un suceso que cause un daño real. es decir, las propuestas del RSI no cambian en este punto.

La "emergencia pandémica" parece utilizarse en el texto como subconjunto de una emergencia de salud pública de importancia internacional ("PHEIC"). Esto puede ser para asegurar la futura conformidad del Acuerdo sobre Pandemias que lo acompaña con la política sobre PHEICs, ya que esto es específico de pandemias mientras que el RSI se refiere a emergencias internacionales de salud pública declaradas de cualquier tipo.

Más restringido que el borrador anterior, que incluía la opción de "... y otras tecnologías sanitarias, pero sin limitarse a esto", definiendo entonces "tecnologías sanitarias" como cualquier cosa que mejore el "bienestar".

Las Recomendaciones Permanentes y las Recomendaciones Temporales vuelven a ser ahora "asesoramiento no vinculante", con la redacción "no vinculante" suprimida anteriormente devuelta al texto (véanse también las notas sobre el artículo 13A y el artículo 42 más abajo).

Esto sigue siendo problemático, sobre todo para los países de renta baja y media. Las "capacidades básicas" del Anexo I incluyen la vigilancia, la capacidad de los laboratorios, el mantenimiento de personal especializado y la gestión de muestras. Muchos países siguen teniendo dificultades para desarrollar y mantener estas capacidades en el caso de enfermedades de alta carga, como la tuberculosis, con una mortalidad bien reconocida como resultado de esta falta de capacidad. El Acuerdo sobre Pandemias expone con más detalle estos requisitos, que exigen muchos recursos. Los países de renta baja corren el riesgo de sufrir daños significativos por el desvío de recursos de los problemas sanitarios de alta carga a un problema percibido predominantemente como una amenaza importante por las naciones occidentales más acomodadas y con mayor esperanza de vida.

Curiosamente, la expectativa de censura "comunicación de riesgos, incluida la lucha contra la información errónea y la desinformación" también se ha relegado ahora al Anexo 1, pero se mantiene esencialmente sin cambios.

Si esto significa algo, el cambio de "debería" a "deberá" parece implicar que todavía se espera que el Estado Parte esté bajo alguna dirección de la OMS. Se trata de una vuelta a la cuestión de la soberanía: el incumplimiento podría utilizarse como motivo para imponer el cumplimiento, por ejemplo, a través de mecanismos financieros (por ejemplo, instrumentos financieros del Banco Mundial o del FMI).

La redacción tiene cláusulas de escape en "dentro de los medios y recursos", pero esto entonces plantea la pregunta de por qué se considera necesario cambiar "debería" por "deberá".

La DG es la única facultada para declarar una emergencia PHEIC o pandémica (véanse las disposiciones del capítulo III sobre la competencia de la DG sobre los comités).

Como en el caso anterior, este punto debe ser facultativo, según convenga en muchas circunstancias. La versión alternativa (bis) que le sigue es mucho más apropiada y coherente con la equidad:

El Director General conserva la autoridad exclusiva para declarar y poner fin a un PHEIC, y el comité de emergencia y los Estados miembros sólo prestan asesoramiento.

Es de esperar que esto refleje cierto reconocimiento del daño causado en la respuesta al covid-19 por el efecto de los viajes internacionales en las economías. Las personas mueren de hambre en los países de renta baja y pierden sus ingresos y su futura educación, especialmente las mujeres, cuando se detiene el turismo. Sin embargo, parece limitarse al personal sanitario.

El artículo 31, párrafo 2 (abajo), citado aquí, en realidad apoya la vacunación obligatoria, lo que choca con las disposiciones sobre consentimiento informado arriba mencionadas, y por lo tanto hay que reformular uno u otro (uno espera que sea el artículo 31).

Utilizar el estado de vacunación como criterio para el derecho de entrada, el derecho soberano de un país aunque se utilizó de forma atroz en la respuesta al covid-19, puede servir de algo cuando una vacuna bloquea la transmisión de una enfermedad grave que aún no prevalece en el país en cuestión.

Es decir, contrariamente al artículo 23, el consentimiento informado no será un requisito para que un Estado miembro realice reconocimientos médicos o inyecte a personas.

La vacunación en el momento de la entrada no sirve para prevenir la importación de enfermedades, ya que no detendrá una infección establecida en el viajero, por lo que la vacunación obligatoria en el momento de la entrada no es una medida legítima de salud pública, independientemente de las preocupaciones en materia de derechos humanos.

La exigencia de reconocimientos médicos, o el aislamiento en caso de negativa, se consideraría en general como último recurso en enfermedades infecciosas muy peligrosas, pero no debería imponerse a la ligera.

Obviamente, esto es inapropiado para el jefe de una organización financiada directamente por aquellos que se benefician de las contramedidas promovidas, debido al conflicto de intereses. Los Estados Partes, como propietarios de la OMS, seguramente deberían proporcionar expertos de su propio pool nacional. Esto reduciría el conflicto de intereses y ayudaría a garantizar la diversidad y la representatividad.

Véase la nota sobre el artículo 47.

Como en el caso anterior, la DG tiene autoridad exclusiva. Esto subraya la importancia de que el cumplimiento del RSI siga siendo voluntario. El actual Director General declaró una Emergencia de Salud Pública de Preocupación Internacional por la viruela del mono, después de sólo cinco muertes en un grupo demográfico muy específico. Esto permitiría, según el nuevo Acuerdo sobre Pandemias y sus disposiciones, que el Director General desencadenara todo el proceso de recomendación de cierres, desarrollo rápido de vacunas, promoción de la vacunación obligatoria, y los beneficios resultantes fluyendo a las entidades actualmente implicadas en la financiación de la agenda pandémica de la OMS.

Como en el caso anterior. Un comité de revisión debe ser independiente para funcionar correctamente, y por lo tanto no puede ser seleccionado por las mismas personas que están revisando. Más aún en este caso, ya que los conflictos son muy probables porque los beneficiarios privados del enfoque propuesto también patrocinan parte del proceso.

Resulta extraordinario que en un comité de revisión sólo tengan derecho a voto y a tomar una decisión quienes hayan sido nombrados por una persona cuyas acciones sean objeto de revisión. Sin embargo, esto se ha colado aquí, y no hay ningún intento por parte de los Estados miembros de proporcionar un mecanismo para una supervisión seria.

Más de la OMS revisándose a sí misma, pero... entonces:

Este artículo 54 alternativo parece un intento por parte de algunos Estados miembros de recuperar cierta supervisión de la DG, asegurándose de que los Estados miembros nombren a miembros del comité con un papel real en la toma de decisiones. De ser así, sería conveniente redactarlo de forma más precisa.

Por supuesto, esto es totalmente incompatible con una votación sobre estas enmiendas propuestas en mayo de 2024.

Por supuesto, es esencial disponer de tiempo para revisar las implicaciones. Cuatro meses es poco para esto, cuatro semanas sería ridículo.

Este artículo será modificado en base a la resolución aceptada previamente por la mayoría de los Estados en la AMS en 2022 (exceptuando aquellos que rechazaron antes de finales de 2023), reduciendo el tiempo de revisión. Así se aclara en un informe de la DG: "27. Las enmiendas a los artículos 55, 59, 61, 62 y 63 del Reglamento, adoptadas por la 75.ª Asamblea Mundial de la Salud mediante la resolución WHA75.12 (2022), entrarán en vigor el 31 de mayo de 2024. Como se comunicó a todos los Estados Partes, la República Islámica del Irán, el Reino de los Países Bajos, Nueva Zelandia y Eslovaquia notificaron a la Directora General su rechazo de las enmiendas mencionadas."

Los nuevos artículos entran ahora en vigor 12 meses después de la votación (artículo 63).

Para los cuatro Estados que rechacen alguna enmienda durante el periodo de revisión, se aplicarán las versiones anteriores de estos artículos. Sin embargo, como antes, se requiere un rechazo activo, en un plazo de 10 o 18 meses respectivamente, o estos Artículos jurídicamente vinculantes se aplicarán automáticamente (Artículo 61).

Otras cuestiones

Nota general sobre terminología.

Países "desarrollados" y "en desarrollo". Tal vez haya llegado el momento de que la OMS abandone el supuesto de que algunos países están más "desarrollados" que otros. Tal vez "ingresos altos", "ingresos medios" e "ingresos bajos", que reflejan la costumbre del Banco Mundial, sean menos colonialistas. ¿Han alcanzado los países "desarrollados" todo lo que el progreso y la tecnología pueden proporcionar?

Esto significaría, por supuesto, que eran "subdesarrollados" hace 20 años y que la tecnología es la única medida del desarrollo, en lugar de la cultura, el arte, la madurez política o la preferencia por no bombardear a los países menos poderosos. La OMS considera menos "desarrollados" a países como India, Egipto, Etiopía y Mali, con miles de años de historia escrita y civilización." Las palabras importan. Promueven, en este caso, una impresión de jerarquía de los países (y por tanto de las personas) en términos de logros o importancia, basada en una cosmovisión muy materialista.

Sobre los autores

David Bell, investigador principal del Brownstone Institute, es médico especialista en salud pública y consultor biotecnológico en salud mundial. Ha sido funcionario médico y científico de la Organización Mundial de la Salud, Jefe de Programa de malaria y enfermedades febriles de la Fundación para Nuevos Diagnósticos Innovadores (FIND) en Ginebra, Suiza, y Director de Tecnologías Sanitarias Mundiales del Intellectual Ventures Global Good Fund en Bellevue, WA, EE.UU.

La Dra. Thi Thuy Van Dinh (LLM, PhD) trabajó en derecho internacional en la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito y en la Oficina del Alto Comisionado para los Derechos Humanos. Posteriormente, gestionó asociaciones con organizaciones multilaterales para Intellectual Ventures Global Good Fund y dirigió iniciativas de desarrollo de tecnología sanitaria medioambiental para entornos de bajos recursos.

原文:

WHO’s International Health Regulations: The intent of the newly released draft remains unchanged

BY RHODA WILSON

ON APRIL 30, 2024

Less than a month before the intended vote, the proposed changes to the International Health Regulations and the draft Pandemic Agreement are still being negotiated. On 16 April, a new draft of the amended International Health Regulations (“IHR”) was released.

In understanding the apparent reversals of some previous proposals in the latest draft, it is important to understand that the covid-19 response demonstrated great success in imposing a new model for responding to outbreaks under the current voluntary IHR. Powerful privately owned foundations with strong connections to the pharmaceutical industry heavily directed this new response.

The newly released draft now states it is non-binding, as is the current IHR, but otherwise, the intent of the draft is essentially unchanged. The intent is to further centralise control of public health within WHO and base response to disease outbreaks on commodities, such as vaccines.

The New IHR Changes Are Merely Cosmetic

By David Bell and Thi Thuy Van Dinh

For two years, the 196 State Parties to the 2005 International Health Regulations (“IHR”) – composed of 194 Member States of the World Health Organisation (“WHO”), and Liechtenstein and the Vatican – have been submitting and discussing proposed amendments to update this agreement. Introduced in the 1960s, the IHR are intended to strengthen national capacities and improve coordination among countries in the event of a health emergency. Though a legally binding agreement under international law (i.e. a treaty), most of the provisions have always been voluntary.

The draft of the IHR amendments and an accompanying draft Pandemic Agreement are both still under negotiation a month short of the intended vote at the World Health Assembly (“WHA”) in late May. Together, they reflect a sea change in international public health over the past two decades. They aim to further centralise control of public health policy within the WHO and base response to disease outbreaks on a heavily commoditised approach, rather than the WHO’s prior emphasis of building resilience to disease through nutrition, sanitation, and strengthened community-based health care.

[Please note: The Pandemic Treaty is also referred to as also referred to as the Pandemic Accord, Pandemic Agreement and WHO Convention Agreement + (“WHO CA+”).]

The Changing Public Health Environment

Public health’s metamorphosis responds to the increasingly directive nature of the WHO’s funding and an increasing participation of the private sector in that funding. Together with a growth of commodity-based public-private partnerships including Gavi (for vaccines) and CEPI (vaccines for pandemics), this has been heavily directed by powerful privately-owned foundations with strong connections to Pharma, who shape the work of these organisations through direct funding and through influence brought directly upon countries.

This became particularly prominent during the response to covid-19, in which prior WHO guidance was abandoned in favour of more directive and community-wide measures including mass workplace closures and mandated vaccination. The resultant concentration of wealth within private and corporate sponsors of the WHO, and increasing impoverishment and indebtedness of countries and populations, both set a precedent for such approaches and left the world more vulnerable to their imposition.

Implications of the New Draft

In understanding the apparent reversals of some proposals amending the IHR in the latest draft, it is important to understand that the covid-19 response demonstrated great success in imposing this new outbreak response paradigm under the current voluntary nature of the IHR. Pharmaceutical corporations successfully sealed highly lucrative contracts directly with States, including public funding for research and development, and liability-free advance purchase agreements. This was supported with heavy sponsorship of media, health, regulatory and political sectors enabling both the high level of compliance and the stifling of dissent.

Centralising more proscriptive powers within the WHO to repeat this business approach under a legally binding agreement would simplify future repetition, but also introduces an element of the unknown into a system already proven to work. These aspects of the previous drafts also presented an obvious focus for public opposition. Pharma has been aware of this reality during the negotiating process.

The latest version of the IHR amendments released on 16 April thus removes wording that would involve Member States “undertaking” to follow any future recommendation from the Director General (“DG”) when he/she declares a pandemic or other Public Health Emergency of International Concern (“PHEIC”) (former New Article 13A). They now remain as “non-binding” recommendations.

This change is sane, conforms with the WHO Constitution, and reflects concerns within country delegations regarding overreach. The shortened review time that passed in rather ad hoc fashion by the 2022 World Health Assembly will apply to all but four countries that rejected them. Otherwise, the intent of the draft, and how it is likely to play out, is essentially unchanged. The World Bank, IMF, and G20 have signalled an expectation that the overall plan will proceed, and rising national indebtedness further increases powers to coerce this.

States are still expected to manage dissenting opinion, and together with the accompanying Pandemic Agreement, the WHO and its partners continue to set up a highly dangerous complex (from a public health, equity, and human rights viewpoint) involving a massive and expensive surveillance system to identify natural viral variants, a requirement for rapid notification by countries, passage of samples by the WHO to pharmaceutical manufacturers of their choice, a 100-day mRNA vaccine delivery bypassing normal regulatory and safety trials, and then a mass-vaccination-based response that will, as seen in the covid-19 response, be pitched as a way to get back to normal. This can still be invoked by the DG alone, simply on his/her perception of a threat rather than actual harm. The pharmaceutical companies will be supported by public funds (See discussion on the Pandemic Agreement), but receive liability-protected profits.

An Unfit and Unready Document

This system will be overseen by the WHO, despite being a beneficiary of Pharma funding, which in turn will be the major financial beneficiary of the pandemic response. The DG personally selects the committee members who may advise and oversee this process (rather than the Member States which are supposed to ultimately be in charge). The WHO receives funding for its emergency agenda from the same organisations and private investors that stand to benefit.

The conflicts of interest and vulnerabilities to corruption in this scheme are obvious. A whole international bureaucracy is already being put in place for this, whose sole reason for existence is to determine that viral variants and minor outbreaks, a natural part of existence, are a threat requiring a specific response that they must then implement. The current DG declared a global emergency over Monkeypox, after just five deaths in a clear and relatively restricted demographic group.

Lastly, the current text of the amendments discussed below looks far from complete. There are internal contradictions, such as clauses both requiring informed consent and, strangely and alarmingly, recommending that this be overridden. The definition provided of a pandemic is as much based on the response put in place as the pathogen or disease itself. By removing the shortened review period and removing overt compulsion, the prior misrepresentation of urgency and outbreak frequency seems to have been recognised.

Yet, this document, and the draft Pandemic Agreement, are still intended to be voted on before the end of May. This completely abrogates the legal requirement within Article 55 of the IHR (2005) and is repeated in this draft, for a four-month review period before any vote. This is not only irrational given the unfinished nature of the text, but inequitable as it disadvantages less-resourced countries in fully assessing likely impacts on health, human rights, and their economies. There are no procedural reasons to prevent the WHO from calling for a later WHA vote after the drafts have been properly reviewed. Member States should clearly demand this.

Significant Proposed Amendments and Their Implications

The key changes and implications of the current draft are summarised below. The proposed changes are found HERE.

The proposed amendments should be reviewed in light of the lack of urgency, low burden, and currently reducing frequency of recorded infectious disease outbreaks and the huge financial requirements to countries – already heavily impoverished and indebted post-lockdowns – for setting up additional international and national bureaucracies and institutions. It must also be assessed in light of the accompanying draft Pandemic Agreement, the apparent conflicts of interest, the concentration of wealth among sponsors of the WHO during the covid-19 response, and the persistent absence of a transparent and credible cost-benefit analysis of the covid-19 response and proposed new pandemic measures from the WHO.

(Text note: Bold text below reflects its use in the draft amendments to denote new text added in this draft.)

The New IHR Changes Are Merely Cosmetic, Brownstone Institute,

28 April 2024

It is useful to have a definition of “pandemic” added to the draft, as it was recently noted elsewhere that without this the entire pandemic agenda is somewhat undefinable. Note the use of “and;” all these conditions must be met.

It is, however, a technically flawed definition. While clause (i) is sensible and orthodox, (ii) will vary between States, meaning that the same outbreak may somehow be a “pandemic” in one country, but not the other. It must also be causing social, economic, or political disruption, and must additionally require a “whole of government approach.”

“Whole-of-government approaches” is an undefinable but popular term in public health, that can be argued to be almost nothing – what really requires a whole-of-government approach? Certainly, no infectious disease outbreak in the past few centuries would readily confirm, as only specific arms of most governments were involved. Some countries had a quite light approach during covid-19, with very limited government redirection, whilst attaining similar or better outcomes than neighbouring states. This would mean that covid-19 would fall outside this pandemic definition despite “spreading to and within” multiple States, and also causing illness.

This definition appears insufficiently thought through, reflecting the rushed nature of this document and its unreadiness for a vote.

“Pandemic emergency” is a new term. The definition includes “or is likely to be,” thus substituting for the change in Article 12 in the previous version that included “potential or actual” to broaden the PHEIC scope to a perceived threat rather than an event causing actual harm. i.e. the IHR proposals are unchanged on this point.

“Pandemic emergency” appears to be used within the text as a subset of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (“PHEIC”). This may be to ensure future conformity of the accompanying Pandemic Agreement with policy on PHEICs, as this is pandemic-specific whilst the IHR addresses declared international public health emergencies of any type.

More restricted than the previous draft, which included an option of “… and other health technologies, but not limited to this,” then defining “health technologies” as anything that improves “well-being.”

Standing Recommendations and Temporary Recommendations are now returned to being “non-binding advice,” with the previously deleted “non-binding” wording returned to the text (see also notes on Article 13A and Article 42 below).

This remains problematic, particularly for low- and middle-income countries. The “Core capacities” in Annex One include surveillance, laboratory capacity, maintenance of specialised staff and sample management. Many countries still struggle to develop and maintain these for high-burden diseases such as tuberculosis, with well-recognised mortality resulting from this lack of capacity. The Pandemic Agreement lays out these resource-intensive requirements in further detail. Low-income countries risk significant harm through resource diversion from high-burden health problems to a problem predominantly perceived as a major threat by better-off Western nations with higher life expectancies.

Interestingly, the censorship expectation “risk communication, including countering misinformation and disinformation” has also now been tucked away in Annex 1, but remains essentially unchanged.

If this means anything, the change from “should” to “shall” seems to imply that the State Party is still expected to be under some direction from the WHO. This is a return to the sovereignty issue – non-compliance could be used as a reason for enforcement such as through financial mechanisms (e.g. World Bank, IMF financial instruments).

The wording has escape clauses in “within the means and resources,” but this then begs the question of why it is deemed necessary to change “should” to “shall.”

The DG alone retains the power to declare a PHEIC or pandemic emergency (See Chapter III provisions below regarding DG power over committees).

As above – this needs to be optional as appropriate in many circumstances. The alternate (bis) version following it is far more appropriate and consistent with equity:

The Director-General retains sole authority to declare and cease a PHEIC, with the emergency committee and Member States giving advice only.

It is hoped this reflects some recognition of the harm done in the covid-19 response through the effect of international travel on economies. People starve to death in low-income countries, and lose their incomes and future education, especially women, when tourism is stopped. However, it appears confined to health staff.

Article 31, paragraph 2 (below) quoted here actually supports mandatory vaccination, clashing with informed consent provisions above, and therefore one or other needs rewording (one hopes this is Article 31).

Using vaccination status as a criterion for right of entry, a country’s sovereign right though used egregiously in the covid-19 response, may serve a purpose when a vaccine blocks transmission of a serious disease not already prevalent in the country concerned.

I.e. Contrary to Article 23, informed consent will not be a requirement for a Member State to perform medical examinations or inject people.

Vaccination at time of entry is of no use in preventing disease importation, as it will not stop an established infection in the traveller, so mandatory vaccination at time of entry is not a legitimate public health measure, irrespective of human rights concerns.

Requirement of medical examinations, or isolation on refusal, would be broadly considered as a last resort in highly dangerous infectious diseases, but should not be imposed lightly.

This is, obviously, inappropriate for the head of an organisation directly funded by those who benefit from the countermeasures promoted, due to conflict of interest. State Parties should, as owners of the WHO, surely be providing experts from their own national pool. This would reduce conflict of interest and help ensure diversity and representativeness.

See note on Article 47.

As above, the DG has sole authority. This underlines the importance of keeping compliance with the IHR voluntary. The current Director-General declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern for Monkeypox, after just five deaths in a very specific demographic group. This would, under the new Pandemic Agreement and the provisions here, allow the DG to trigger the whole process of recommending lockdowns, rapid vaccine development, promotion of mandatory vaccination, and resultant profits flowing to entities currently involved in funding WHO’s pandemic agenda.

As above. A review committee must be independent to function properly, and therefore cannot be selected by the same people they are reviewing. All the more so here, as conflicts are so likely as private beneficiaries of the proposed approach also sponsor part of the process.

It is extraordinary for a review committee that only those appointed by a person whose actions are a subject of the review would have a right to vote and make any determination. However, this has crept in here, and there is no attempt by Member States to provide a mechanism for serious oversight.

More of the WHO reviewing itself, but…then:

This alternate Article 54 seems an attempt by some Member State(s) to wrest some oversight back from the DG, ensuring Member States nominate committee members with an actual decision-making role. If so, it may benefit from tightening of the wording.

This is, of course, completely incompatible with a vote on these proposed amendments in May 2024.

Time to review implications is of course essential. Four months is short for this, four weeks would be ridiculous.

This Article will be modified based on the resolution accepted previously by most States at the WHA in 2022 (excepting those who rejected prior to the end of 2023), reducing the review time. This is clarified in a report from the DG: “27. The amendments to Articles 55, 59, 61, 62 and 63 of the Regulations, adopted by the Seventy-fifth World Health Assembly through resolution WHA75.12 (2022), will enter into force on 31 May 2024. As communicated to all States Parties, the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, New Zealand and Slovakia notified the Director-General of their rejection of the above-referenced amendments.”

The new Articles now come into force 12 months after a vote (Article 63).

For the four States that reject any amendment during the review period, then prior versions of these Articles apply. As before, however, active rejection is required, within 10 or 18 months respectively, or these legally binding Articles automatically apply (Article 61).

Other issues

A general note on terminology.

“Developed” and “developing” countries. It is perhaps time that the WHO moved on from the assumption that some countries are more “developed” than others. Perhaps “high-income,” “middle-income” and “low-income,” reflecting World Bank custom, are less colonialist. Have “developed” countries attained all that progress and technology can provide?

This would of course mean that they were “undeveloped” 20 years ago and that technology is the only measure of development, rather than culture, art, political maturity, or a preference for not bombing less powerful countries. The WHO considers countries such as India, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Mali, with thousands of years of written history and civilization, less “developed.” Words matter. They promote, in this case, an impression of a hierarchy of countries (and therefore people) in terms of attainment or importance, based on a very materialistic worldview.

About the Authors

David Bell, Senior Scholar at Brownstone Institute, is a public health physician and biotech consultant in global health. He is a former medical officer and scientist at the World Health Organisation, Programme Head for malaria and febrile diseases at the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) in Geneva, Switzerland, and Director of Global Health Technologies at Intellectual Ventures Global Good Fund in Bellevue, WA, USA.

Dr. Thi Thuy Van Dinh (LLM, PhD) worked on international law in the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Subsequently, she managed multilateral organisation partnerships for Intellectual Ventures Global Good Fund and led environmental health technology development efforts for low-resource settings.

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?