(99) Section 4: The Rise and Fall of Polytheistic Civilization II

Chapter 1: The Indus

6-2 The Buddha’s Itinerant Teachings

Much is known about the Buddha’s missionary activities leading to his death. Instead of traveling throughout the Indian subcontinent, the Buddha focused on the Ganges Basin.

But the Kingdom of Magadha wasn’t the sole state of power in this part of the world. The Kosala Kingdom (present-day Uttar Pradesh) was just as robust. And it was in Kosala that you would find the ancient city of Sravasti, whose outskirts were the location of a well-known monastery known as Jetavana, a locale which graces the beginning pages of one of Japan’s most famous epic, the Tale of the Heike. The name Jetavana comes from the famous episode involving the wealthy Buddhist devotee Sudatta. Sudatta had appealed for the construction of a spiritual basecamp where Buddhist ascetics and monks could continue their training indoors during the rainy season and proposed buying the forested land from Prince Jeta, who agreed to sell the land on condition that it be paved with gold. Prince Jeta didn’t really believe Sudatta would be able to carry out the absurd request. But when Sudatta began paving the land with gold, the prince was shocked. Moved by his devotion, the prince decided to donate the land to the Buddha, and the name Jetavana vihara stuck (the monastery, vihara, of Prince Jeta’s forest, vana, [“forest or land”]).

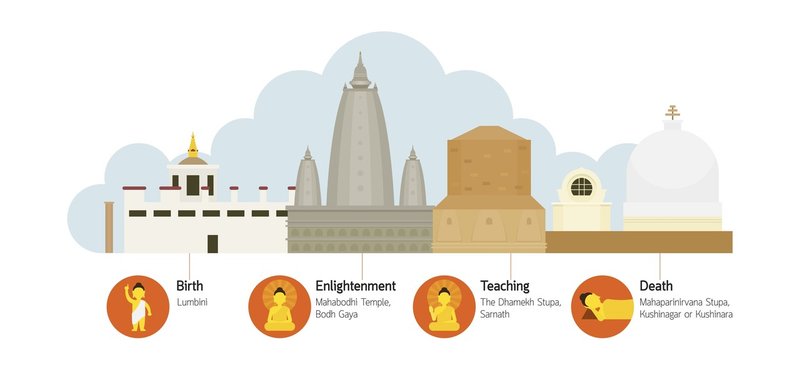

▲ 4 holy Sites of Buddhism ©MuchMania

The Kingdom of Kosala was also the accomplice to a horrible tragedy involving the Buddha’s clan, the Shakyas.

It all started when the ruler of Kosala, Pasenadi, became a follower of the Buddha and left his home country to join him as one of his missionaries.

While Pasenadi was on his mission, his son, Prince Virudhaka, carried out a rebellion and claimed the throne. Hearing the news, Pasenadi made his way to Magadha to enlist help from his son-in-law, Ajatashatru, but died before he could reach him. To make matters worse, the new King Virudhaka ignored the Buddha’s warning and proceeded to annex the capital of the Shakya clan, Kapilavastu, seizing it for himself.

It’s unclear what happened to the royal family of the Buddha’s familial Shakya tribe, though a people known as the Sakiya, who call themselves the decedents of this Shakya tribe, still survive today in present-day Nepal. Regardless, we know the Buddha witnessed the slaughter of his own people and the ruin of his own country. He had experienced first-hand the Buddhist saying, “all things must pass.”

And so from Rājagṛiha the Buddha and his disciples embarked on a journey to spread the good word. The journey, however, would be his last. On the way, the Buddha fell seriously ill and became close to death, but recovered. Ananda, one of the Buddha’s disciples, was overjoyed. The Buddha would never leave this earth without leaving behind some final pearls of wisdom. Or so he thought. For the Buddha, there was nothing left to say. He had taught everything he needed to teach.

The Buddha chastised Ananda for expecting some arcane teachings like those found in Hinduism.

But, the pilgrimage continued, despite the Buddha’s worsening condition. A blacksmith named Chunda had invited him and his disciples in for a meal at his home, a decision that would leave the Buddha with severe stomach pain. Although they would make it to the capital of Malla, Kushinara (present-day Uttar Pradesh), the Buddha would not survive the ordeal. Buddhism believes this is when the Buddha entered nirvana. The exact cause of the Buddha’s demise remains a mystery, though one theory points to death by poison mushroom.

Kushinara represents the last of the four holy sites in Buddhism, the other three being the birthplace of the Buddha, Lumbini, the location where he is believed to have attained enlightenment, Bodh Gaya, and Sarnath, where the Buddha is thought to have delivered his first teaching.

Cremated Remains

Following his death, the Buddha’s body was cremated in accordance with Indian tradition.

In Hindu society, a society built on the idea of samsara, the body is nothing more than a vessel for Atman. This is why it is customary to, after one’s death, cremate this “shell” and scatter the ashes in a river. But in the Buddha’s case, while cremation was carried out, the typical scattering of remains was not. The Buddha had achieved liberation from samsara, after all—he had become the eternal embodiment of truth.

▲ Emperor Ashoka the Great on Elephant, 1st century BC. Found in the Collection of Buddhist Monuments at Sanchi ©Fine Art Images

In early Buddhism, devotees would worship Stupas (hemispherical, commemorative monuments) containing sharira or relics of the Buddha left over after his cremation and would reaffirm their faith inside the sanctuary’s grounds.

Initially, the Buddha’s relics were divided between the eight prominent Buddhist nations, and as Buddhism spread, the relics were divided even further. But the center of Buddhist temples was not always the main hall with an image of the Buddha; in the beginning, there was the relic-containing stupa. In Japan, this became the goju no to (五重の塔), literally “five-storied tower,” and in Myanmar, the “pagoda.”

Later, as Buddhist relic worship intensified, a multitude of forgeries surfaced. But not all claims were forgeries. Sometimes, the remains of Buddhist saints were, over time, considered to be those of the Buddha. Someone once exclaimed to me that, “if you round up the remains purported to have belonged to the Buddha, you would have a several-meter-tall giant.”

Of course, that isn’t to say no real remnants of the Buddha exist. In the eighteenth century, a team of French archeologists excavating a site believed to be once a part of the Kingdom of Malla discovered a period-correct cremation urn containing remains assumed to belong to the Buddha. Ultimately, the discovery was gifted to the predominantly Buddhist nation of Thailand, who then gave a portion of the ashes to Japan as a display of friendship between the two countries. Today, the ashes can be found in Nittai-ji temple in Nagoya.

Buddhism’s influence has infiltrated even sushi restaurants in Japan, where white rice is referred to as shari from the Japanese busshari (Buddha’s ashes) because of its resemblance to the finely divided ashes of the Buddha.

For some time after the Buddha’s death, his teachings were conveyed orally through memorization and were prone to misunderstandings and conflicting orthodoxy. So the Buddha’s disciples decided to come together to transcribe his teachings in gatherings known as the Buddhist Councils, the first of which was held soon after Buddha’s death with an attendance of five hundred monks or bhikkhus.

Mahakassyapa and Ananda, two of the ten principle disciples of the Buddha, presided over the first Buddhist Council, and King Ajatashatru was the danapati (“lord of alms”) or sponsor.

It wasn’t until some two hundred years after the Buddha’s death that Buddhism finally spread throughout the Indian subcontinent. This was thanks to the efforts of King Ashoka (reigned c. 268 – c. 232 BC), the third monarch of the Maurya dynasty who united nearly the whole of India, and who also happened to be a passionate Buddhist.

He’s perhaps most notably remembered for his “pillars of Ashoka,” towering monuments of stone, sometimes some fifteen meters tall, and often embellished at the crown with elaborate carvings of lions, elephants, and horses. Some designs are even used in the Coat of Arms of India. But the original function of the stone pillars was to propagate Buddhism.

So why exactly was King Ashoka so passionately Buddhist? The answer has a bloody past.

< Read the next installment April 15>

Editor/ Noriko Knickerbocker , Aquarius Ltd.

Translator/ Matthew Hunter , Aquarius Ltd.

©Motohiko Izawa 2018-2019 All rights reserved. No reproduction or republication without written permission.

Izawa tackles for the first time the mysteries of the world in a historical journey of intrigue and cross-cultural understanding.