(104) Section 5: The Rise and Fall of Polytheistic Civilization II

Chapter 1: The Indus

9-1 The Dawn of Amida and the Silk Road

So what became of that singular treasure of the Indus after it made its way across continents and cultures?

An interesting point of departure for later Buddhism is Mahayana Buddhism’s Lotus Sutra, in which Shakyamuni himself guarantees all of us the possibility of becoming a Buddha, imperfections and all.

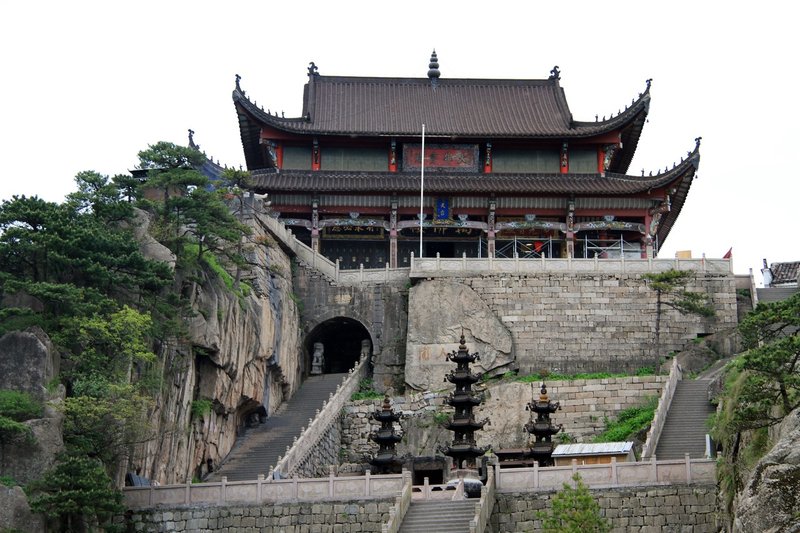

This is why the Sui dynasty monk Zhiyi deemed it the finest sutra ever written. Having confined himself to China’s Tiantai Mountain for intensive study, Zhiyi eventually went on to become, in essence, the founder of Tiantai Buddhism and later “Master Tiantai.”

△ Tiantai Temple, Mount Jiuhua, Anhui, China © shanin

And it was the Japanese Buddhist monk Saicho (c. 767-822) who first ventured from his native Japan, the terminus of the Silk Road, to China to study the Tiantai school of Buddhism. On his return to Japan, Saicho worked hard to transform his school of Buddhism, the Tendai Lotus School (Tendai-hokke-shū), into a full-fledged religion officially acknowledged by the imperial court. In addition to building the Tendai monastery, Enryaku-ji, on Mount Hiei in northeast Kyoto, a temple complex that overlooked Japan’s then capital of Kyoto (Heian-kyo), Saicho wrote the treaty Sange Gakushoshiki (“Regulations for Students of the Mountain School”) for submission to Emperor Kanmu (737-806, reigned 781-806) as a petition for recognition, earning, eventually, imperial patronage and an official place in formal Japanese Buddhist education.

Here, in Sange Gakushoshiki, Saicho makes an interesting point:

What is the treasure of the nation? The religious nature is a treasure, and he who possesses this nature is the treasure of

the nation. That is why it was said of old that ten pearls big as

pigeon’s eggs do not constitute the treasure of a nation, but

only when a person casts his light over a part of the country

can one speak of a treasure of the nation. A philosopher of old

once said that he who is capable in action but not in speech

should be of service to the nation; but he who is capable both

in action and speech is the treasure of the nation.

(Sources of Japanese Tradition: From Earliest Times to 1600,

compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Donald Keene, George

Tanabe, and Paul Varley, New York: Columbia University Press,

2001.)

He and his successors took this declaration to heart and poured their hearts into cultivating the next generation of Tendai faithful.

△ Buddha statue, Tiantai Temple © shanin

Saicho lived at a time in Japanese history known as the Heian period, when the seat of government was at Heian-kyo (present day Kyoto), and the Imperial Court—that is, the emperor, along with his circle of nobles and courtiers—ruled over Japan. But at the end of the twelfth century, a new class of wealthy, reclamation landed farmers replaced the weakened central government and emerged, through their own affluence and self-armament, the political and military heart of the nation.

This was the warrior class or samurai. And their first order of business was to establish their own military dictatorship not in Kyoto where the emperor resided, but in Kamakura, some three hundred kilometers to the east. As their leader, the samurai had what they called the Sei-i Taishogun ("Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force Against the Barbarians") or shogun for short.

Shogun originally referred to the emperor-appointed army commander in charge of expelling “barbarians.” The first to become shogun was not a member of the aristocracy but of the samurai class—Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-99), a man who also went on to create a completely new type of government. For the first time, a shogun commissioned by the emperor as chief warrior had used his power to put in place a military government, becoming the de-facto leader of the nation. The headquarters where the shogun was stationed was the shogunate, and the period when the Kamakura shogunate governed Japan is known as the Kamakura period.

For the hundred and fifty or so years leading up to the fall of the Kamakura shogunate at the hand of the emperor (1185-1333), the samurai had replaced the emperor and imperial family as the cultural leaders of the nation and had ushered in a new era of down-to-earth popular culture. Buddhism had also transformed. Heian Buddhism, which was an integral part of court life, gave way to the Kamakura New Buddhism.

Its leader was Honen (1133-1212).

Honen studied Tendai doctrine at Enryaku-ji on Mount Hiei and was considered one of the monastery’s greatest scholars. Still, something bothered him. Nowhere in the Lotus Sutra could one find any specific instructions on becoming a Buddha—it was enough to drive him to find a path to Mahayana Buddhism’s fundamental purpose of universal salvation. In the end, he found his answer not in Shakyamuni Tathagata but in the celestial Buddha, Amitabha Tathagata. Through a fervent belief in Amitabha, Honen made it his purpose to be reborn in the Amitabha’s Pure Land. As long as one could be reborn in the Pure Land, anyone could achieve Buddhahood under the tutelage of Amitabha.

△ Amitabha Tathagata © Waikeat

So what kind of Buddha is Amitabha? Amitabha Tathagata shares the same title with Shakyamuni Tathagata, implying that Amitabha too is a Buddha who has attained enlightenment. (The exact meaning of Tathagata remains unclear, but the generally accepted interpretation is one who has experienced enlightenment.)

Mahayana Buddhism sees the historical Buddha as a mere appearance in one of multiple worlds of existence. In fact, the Buddhist world view, not unlike the idea of multiverses in science-fiction, believes there to be three thousand parallel “realms.” From this perspective, it isn’t terribly difficult to imagine the existence of another tathagata teaching the path to salvation.

Here we come back to the Amitabha Tathagata. The idea of Amitabha is not an Indian concept but one that arose quite suddenly somewhere on the Silk Road around the second century before making its way to Japan via China.

What sets Amitabha Buddha apart from the numerous other buddhas in existence is the former’s so-called Primal Vow, in which he promises to renounce enlightenment unless all sentient beings are born into his land and achieve the same great awakening through the practice of the nembutsu, an invocation of Amitabha.

Honen’s One-Sheet Document—A Life and Teachings

The complicated part, however, is determining what exactly the nembutsu means. In China and Japan, it meant, at least initially, imagining Amitabha and the Pure Land. This is why Heian-period nobles constructed not only temples that deified statuary of Amitabha but also temple grounds that recreated the Pure Land paradise in the form of elaborate gardens—all so that they could imagine the world of Amitabha in their daily lives. The Japanese refer to this as kanso (contemplation) nembutsu.

Kanso nembutsu greatly elevated Heian art through the countless elaborate Buddhist sculptures, ingenious works of architecture and landscape design, and numerous works of pictorial art it inspired. But to Honen, the exclusive nature of these works, accessible to only the privileged, i.e., the aristocracy, did nothing to lead the masses to salvation. He believed that, because Amitabha’s Primal Vow reflected the essential purpose of Mahayana Buddhism, Amitabha would have not been interested in a nembutsu practice that excluded all except the very wealthy and privileged.

This is why Honen considered reciting namu amida butsu (I take refuge in Amida Buddha), that is, a verbal confession of faith in Amitabha, as the most important act of faith. In contrast to the kanso nembutsu was the kuju nembutsu (recitation nembutsu). With its methodology already established in China, the kuju nembutsu had been put into practice in Japan during the Heian period, but was considered a mere simplification of the official kanso nembutsu.

Honen, however, believed the kuju nembutsu to be the only proper path to salvation. Of course, this was because it was in-line with the fundamental objective of Mahayana Buddhism—saving more people.

Firm in his belief that the kuju nembutsu was the only way to salvation, Honen wrote and published his own convictions in the form of the Senchaku Hongan Nembutsushū (Passages on the Selection of the Nembutsu in the Original Vow). Still, while fully aware of the low literacy rate, Honen had no delusions of printing his work and changing the world with his “passages” during the Kamakura period, a point in time, of course, without modern printing technologies. Instead, he left the monastery at Mount Hiei and sought to edify as many disciples as he could. He was about to dedicate his life to the spread of the kuju nembutsu.

< Read the next installment July 1 >

Editor/ Noriko Knickerbocker , Aquarius Ltd.

Translator/ Matthew Hunter , Aquarius Ltd.

©Motohiko Izawa 2018-2019 All rights reserved. No reproduction or republication without written permission.

Izawa tackles for the first time the mysteries of the world in a historical journey of intrigue and cross-cultural understanding.