(100) Section 4: The Rise and Fall of Polytheistic Civilization II

Chapter 1: The Indus

7-1 Mahayana Buddhism’s “Emptiness” and “Zero”

So, what about King Ashoka (reigned c. 268 – c. 232 BC)? To start, we know he was the third monarch of the Mauryan dynasty, credited with propagating Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent. But what made him tick?

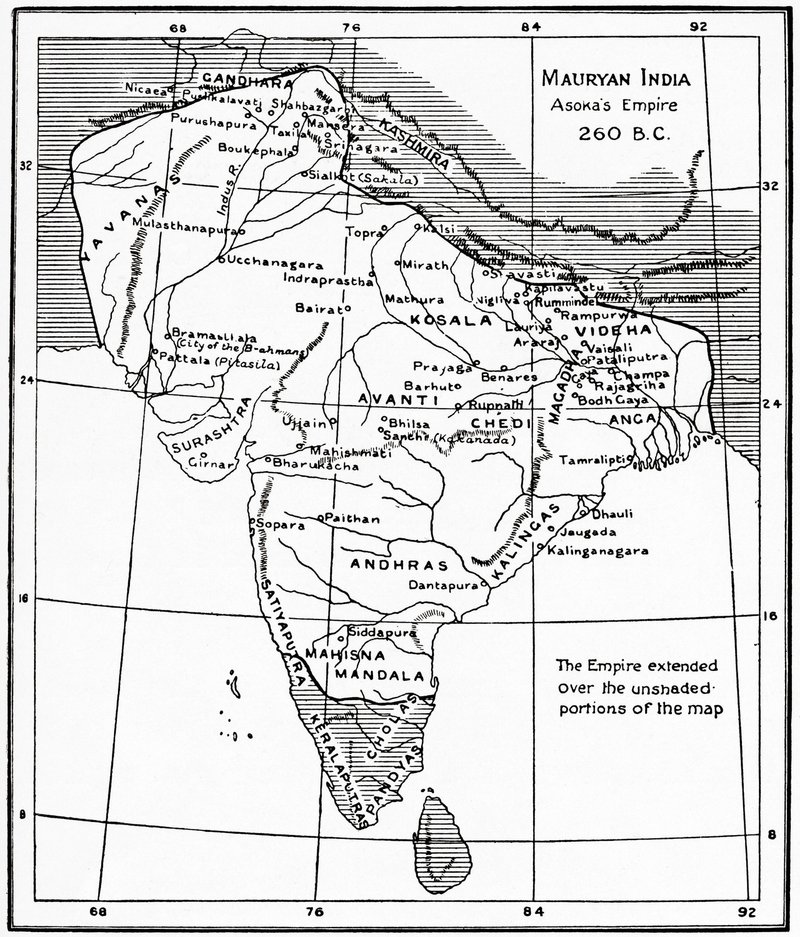

Having inherited the territories accumulated by both his grandfather, Chandragupta (r. c. 321 – c. 297 BC), and father, Bindusara (r. c. 297 – c. 273 BC), King Ashoka ruled over large swathes of present-day India, as well as sections of present-day Afghanistan, and would go on to build the largest empire in ancient Indian history. With the capital of Pataliputra (Patna in Indian state of Bihar) and the agricultural middle Ganges basin as his empire’s core, Ashoka brought wealth to his kingdom through domestic and international trade.

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing. When the monarch conquered the city of Kalinga, the local population pushed back. He responded by murdering them. But the king’s feelings of victory quickly descended into feelings of guilt and regret, prompting him to seek salvation in the Buddha. Rather than put his efforts into forceful conquests, Ashoka decided to rule through Buddhism and quickly sprang to action.

He would now place himself on equal grounds with his people, embrace the teachings of the Buddha, and devote himself to carrying out the Buddha’s word. Citizens were to live with a sense of mercy, causing no harm to any living creature. The state would also operate with a merciful heart and prioritize its people. Roads were maintained and improved, wells were dug, hospitals were built. In many ways, it was humankind’s first welfare state.

▲ Map of Mauryan India, Ashoka's Empire, 260 BC. © Classic Image

Ashoka also stressed the virtue of ahimsa, the concept of causing no harm. To carry out his mission, the king toured the nation, maintained Buddhist sites, and erected what we know today as Ashoka’s pillars. We know that the precise location of Siddhartha Gautama’s place of birth is Lumbini (present-day Nepal) precisely because of his grand columns.

Some pillars contain not only Buddhist teachings, but also inscriptions ascribed to King Ashoka, a man clearly committed to spreading the Buddha’s good word. Present-day India may be dominated by Hinduism, but it is Ashoka’s pillars that appear on the Indian rupee as relics representative of Indian culture.

The fruit of Ashoka’s efforts was a Buddhist expansion beyond the confines of the Indian state to neighboring territories. Buddhist faithful lauded Ashoka as the “wise ruler,” a monarch who eventually became the source of numerous legends, one of which that claims Buddhism put down its roots in Sri Lanka in southern India thanks to King Ashoka’s son Mahinda, who successfully converted King Devanampiya Tissa.

The Buddhist Schism

About one hundred years after the Buddha’s death, doctrinal differences drove the Sangha (the Buddhist monastic community of bhikkhus or monks) of disciples to split into two groups. This “fundamental schism” created two Buddhist orders: the Sthavira nikāya (“Sect of Elders”), which aimed to maintain the traditional discipline, and the Mahāsāṃghika school, which sought a more progressive slant.

While the direct basis of the schism remains unclear, its fundamental cause seems to have risen from Sthavira nikāya’s strict adherence to doctrine and its opposition to the Mahāsāṃghika school’s significantly more flexible approach.

Mahāsāṃghika went on to create a set of beliefs that were, at least in terms of doctrine, a complete departure from traditional Buddhism, which its founders called “Mahayana” or “Great Vehicle” in Sanskrit.

Adherents to the new Mahayana Buddhism believed that, different from conventional Buddhism’s orientation toward enabling ascetics like its founder, the Buddha, to achieve enlightenment, their new Buddhism was for everyone—everyone deserved salvation.

Mahayanaists mocked Sthavira nikāya’s Buddhism, calling it “Hinayana” or the “smaller (inferior) vehicle.”

This is similar to the Christian belief that, in contrast to the fundamental Jewish belief that Yahweh identified the Jews as the chosen people, Jesus extended God’s salvation to all humanity, which is why Christians decided on the title of the “Old Testament” (the old covenant) for the Jewish bible and the “New Testament” for the book of Jesus’s teachings.

Not surprisingly, the derogatory and pejorative “smaller vehicle” (Hinayana) is no longer used to refer to any form of Buddhism. Today, pre-Mahayana Buddhist factions are referred to by “Theravada” (thera for “elder,” vada for “doctrine”).

As you might expect, Mahayana Buddhism replaced the elite monastic asceticism with an approach that sought salvation for all in the real world, regardless of marriage status.

Buddhist history has often focused on the method of the Mahayana scholars’ philosophical completion of the Buddha’s teachings. But I think this philosophical completeness sought by Mahayana theorists has hardly anything to do with Mahayana Buddhism’s influence on future generations.

Of course, I realize my position isn’t held by everyone. But before I talk more about my controversial point of view, I have to discuss first this idea of “philosophical completeness.”

< Read the next installment May 1 >

Editor/ Noriko Knickerbocker , Aquarius Ltd.

Translator/ Matthew Hunter , Aquarius Ltd.

©Motohiko Izawa 2018-2019 All rights reserved. No reproduction or republication without written permission.

Izawa tackles for the first time the mysteries of the world in a historical journey of intrigue and cross-cultural understanding.