The Sanctions Sieve, The Wire China, Apr. 2, 2023.

The U.S. government is trying to stop China from selling chips to Russia that aid its war effort. It’s failing.

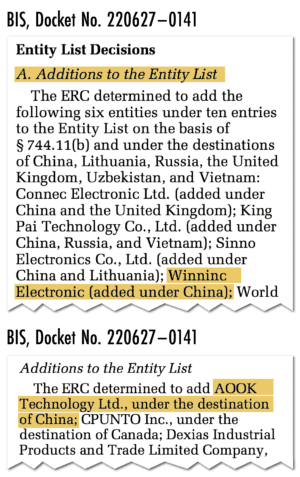

n June 2022, the U.S. Commerce Department placed Shenzhen-based Winninc Electronics on the Entity List. Seven months later, it sanctioned another Shenzhen-based firm, AOOK Technology, as well. As exporters of semiconductors and electronic components, the companies were accused of supporting Russia’s military and defense industrial base. By sanctioning them, the U.S. hoped to stem the flow of components made by American companies from enabling Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The flow, however, continued. An investigation by The Wire has found that there are at least four companies directly linked to Winninc and AOOK that are not sanctioned, with many of them continuing to ship chips to Russia. The discovery highlights how critical components, including those made by prominent U.S. firms, may still be ending up on the Ukrainian battlefield, despite one of the most expansive sanctions regimes ever attempted by the U.S. government.

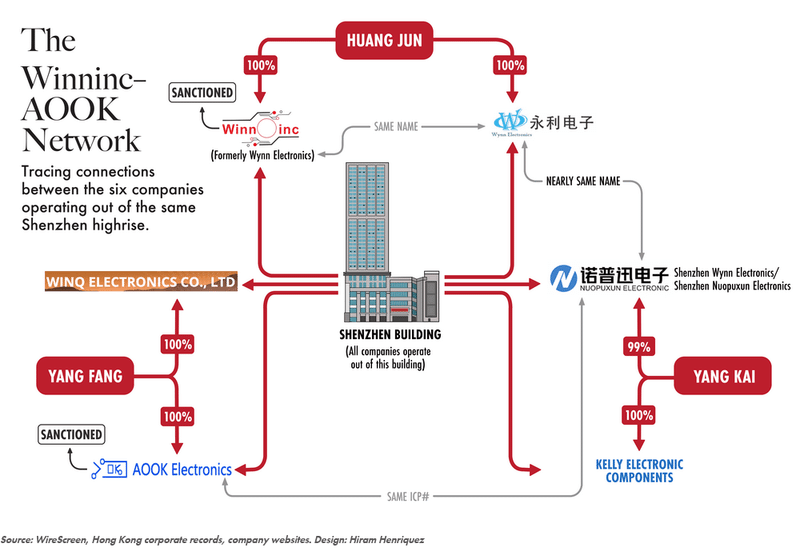

In the case of Winninc and AOOK, this is largely because their network is more like a multi-headed hydra than a traditional, top-down corporate entity — and U.S. sanctions have only taken down two of the creature’s heads.

The six companies operate under different websites and names, but The Wire linked them to one another using ownership data from WireScreen, website registration numbers, Hong Kong corporate records and addresses. All of the firms operate out of the same high-rise in Shenzhen.

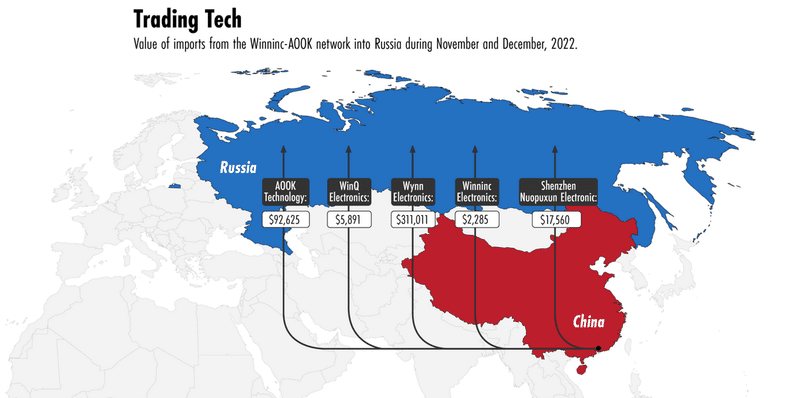

In November and December alone, the most recent months for which Russian customs information is available, the network of companies sold nearly half a million dollars worth of components to Russia, according to data from Import Genius. Many of these components were made by major American semiconductor firms like Texas Instruments and Analog Devices, as well as European firms such as Infineon Technologies.

The Commerce Department declined to comment on what intelligence it used to place Winninc and AOOK on the Entity List, which prohibits U.S. exports to the named company without a special license. It also declined to comment on whether the U.S. government is aware of the four other firms.

In a statement to The Wire, a Commerce spokesperson said that the department is “constantly tracking trade flows of consumer electronics and other items using open source, proprietary, and classified sources in order to identify actors that present concerns for U.S. national security and foreign policy objectives … We are also continually working with our interagency partners to refine and align our controls to continue to deny Russia the items it needs to sustain its war machine.”

But analysts say many Chinese companies are well versed at getting around the tough restrictions on Russia’s economy.

“If I am a well established Chinese company, and I am engaged in this illegal activity, I have a lot to lose,” says Gregory Allen, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and former Pentagon official. “If I am a special purpose company set up for this, I am prepared to shut it down and set up a new one with the same employees. For some companies, their profession is export control evasion. With those, it is a whack-a-mole type of a game.”

Source: The Wire China

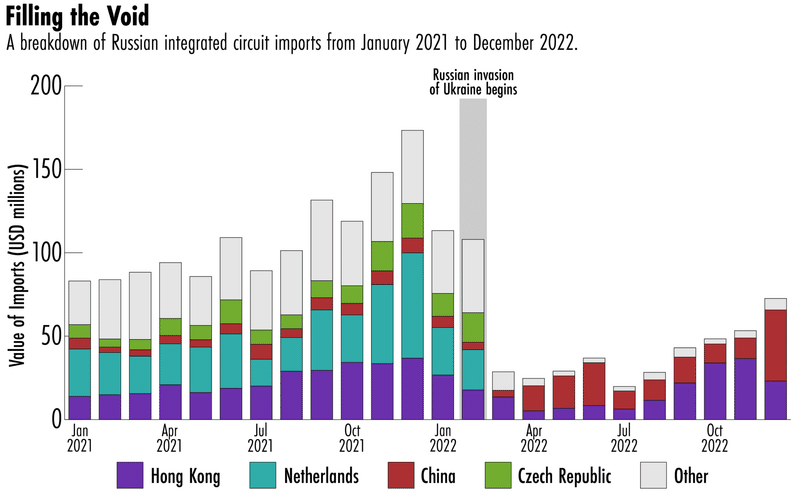

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. announced a raft of sanctions and export controls that restrict essentially all American semiconductors from being sold to Russia. Shipments to Russia by major electronics exporting nations, such as the Netherlands and Germany, sharply dropped off. But shipments from China — as well as other countries like Turkey — have helped Russia fill the gap. After an initial dip, China’s overall exports of integrated circuits to Russia increased by about 200 percent, according to an analysis by Silverado Policy Accelerator, the Washington, D.C.-based geopolitics think tank.

Some of these chips are made in China, while others are made elsewhere and shipped to Russian customers by Chinese resellers, like the companies that make up the Winninc-AOOK network. In 2021, before the invasion, only 27 percent of Russian integrated circuit imports came from China and Hong Kong; now, China and Hong Kong make up about 88 percent of Russia’s chip imports.

“It becomes concerning to see that the void is being filled by new entrants, in particular China,” says Sarah Stewart, the executive director at Silverado. “The sanctions have not delivered the death blow. We need to do more.”

Source: The Wire China

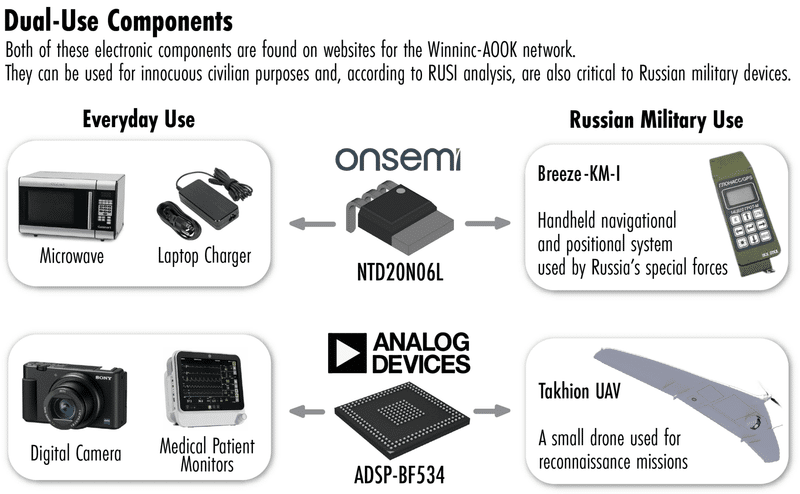

It’s difficult to know how to do more, however, partly because chips are so called ‘dual-use items,’ meaning that they are used both for military and civilian purposes. Many of the chips required for the battlefield use relatively basic technology and are widely available commercially. An analysis of 27 Russian weapon systems by Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a UK think tank, showed that only 18 percent of components in the systems are covered by U.S. export controls.

“The chips that can deliver potent military performance can be quite old,” says Allen, the analyst at CSIS. “Just because it is old, doesn’t mean it is not powerful.”

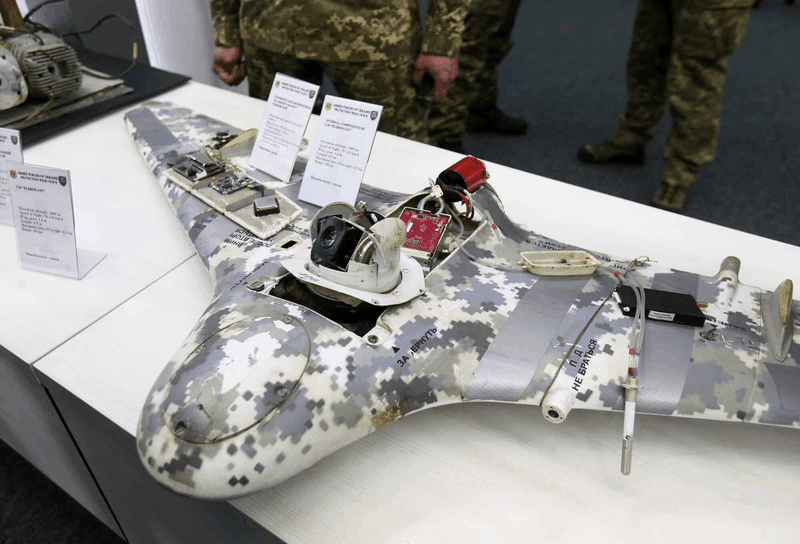

While there are already restrictions on selling leading edge chips to China, the chips that the Winninc-AOOK network is selling do not appear to be particularly advanced; many of them can be used in microwaves or laptop chargers, for example. But many of these same chips are also critical to Russian drones and special navigation systems, according to RUSI.

You can’t count on the government in China. They are encouraging circumvention if not willfully looking the other way.

The Wire was unable to identify the ultimate end use of Winninc-AOOK components in Russia. The Winninc-AOOK companies did not respond to multiple emails and calls from The Wire.

“The big picture is that U.S. export controls typically require a cooperative foreign host government,” says Ivan Kanapathy, a former China focused National Security Council official under Presidents Trump and Biden. “When you don’t have that, things fall apart. That is what we are seeing. You can’t count on the government in China. They are encouraging circumvention if not willfully looking the other way.”

None of the companies in the Winninc-AOOK network have any state-ownership, according to WireScreen data; they seem to be private companies profiting off Russia’s demand rather than participating in a government-backed effort. They may have Beijing’s tacit support, however — the Chinese government has emerged as a key partner for Russia over the past year. After the two countries declared their ‘no limits’ partnership just weeks before the Ukraine invasion, China has continued to buttress Russia diplomatically, most recently when Xi Jinping met Putin at the Kremlin.

At the meeting in Moscow, Xi stressed that “there is a profound historical logic for China-Russia relationship to reach where it is today,” according to the Chinese readout from the meeting. “China and Russia are each other’s biggest neighbor and comprehensive strategic partner of coordination. Both countries see their relationship as a high priority in their overall diplomacy and policy on external affairs.”

The U.S. government has made increasingly strong statements decrying the Russia-China partnership. Officials have also warned the Chinese that providing lethal weapons to Russia, which they have reportedly considered, would be seen in Washington as a dramatic escalation.

The status quo, meanwhile, consists of enterprising companies like AOOK Technology making the “integrated circuit business easy,” as its website states, and helping “customers quickly find the electronic components as they need.” Over the last year, customers in Russia have been particularly in need — and true to their mission, the Winninc-AOOK network has made buying chips easy.

SHENZHEN SHENANIGANS

The office building is an unremarkable, light brown high-rise in Shenzhen’s dense downtown with a budget hotel on the ground floor.

Inside, the Winninc-AOOK network buys and sells chips to countries far and wide. The company websites all advertise roughly the same group of products, and describe their business with uncannily similar language1 Four of the six companies use some form of ‘Win’ or ‘Wynn’ in their names.

Beyond sharing an address and a roster of merchandise, corporate records from Hong Kong and mainland China provide clues that link the companies together. Three individuals — Yang Kai, Yang Fang and Huang Jun — repeatedly emerge as shareholders in the six companies, according to WireScreen and Hong Kong records. There is little public information about their backgrounds, but a LinkedIn page for Yang Fang says she is the manager of Wynn Electronics and has also worked at Winninc.

The Winninc-AOOK companies, reached by phone, repeatedly hung up. And replying to an email with a detailed list of questions, Yang Fang replied, “I don’t know what you’re talking about, and I don’t know the companies you’re talking about! Please don’t harass me!!”2

The oldest company in the group seems to be Winninc, which was sanctioned last summer. It was registered in Hong Kong in 2011, and was previously named Wynn Electronics. Huang Jun is listed as the company’s only shareholder and director. Another company registered in mainland China with the same name, Wynn Electronics, also lists Huang Jun as its sole shareholder, according to Wirescreen.

Records for another firm operating out of the same address with a nearly identical name, Shenzhen Wynn Electronics, is key to unraveling more firms within the network. Shenzhen Wynn itself, which is 99 percent owned by Yang Kai, operates under two different websites and two different English names. Yang Kai wholly owns another company, Kelly Electronic Components, which is also housed in the Shenzhen high-rise. (Kelly Electronic is the only company in the network that does not appear to be exporting to Russia, according to Import Genius data.)

Shenzhen Wynn also links the network to AOOK Technology, the second firm sanctioned by the Commerce Department. Shenzhen Wynn and AOOK, which is registered in Hong Kong and is owned by Yang Fang, share the same ICP number, a state issued website permit number. The month after Winninc was sanctioned, Yang Fang set up in Hong Kong what seems to be the newest company in the network, WinQ Electronics.

Despite this dizzying array of corporate entities, the network’s focus on the Russian market is consistent and longstanding.

In November 2016, Wynn Electronics posted on their Facebook page, “Happy Thanksgiving DAY! From now on, Wynnele has russian staffs joining us. Anyone need electronic components in Russia, can contact us now. [sic]”

Source: The Wire China

The next year, Wynn Electronics, which has a special tab for Russian language on its website, hosted a booth at the Moscow Chip Expo. The company’s press release for the event says that the company is “well known in Moscow market. [sic]”

Russia’s domestic chip industry is small and far from state of the art, requiring Russian firms to import chips and chip making equipment from companies overseas. Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, prompting Western countries to impose a strict sanctions regime. In the month after the invasion, global exports of integrated circuits to Russia dropped by over 70 percent, according to data from Silverado.

Trade data from Import Genius shows that the Winninc-AOOK companies exported at least $2.5 million worth of goods to Russia in 2022.3 Before Winninc was sanctioned, it was the Winninc-AOOK company doing the most trade with Russia; in November and December, however, Wynn Electronics, which remains un-sanctioned, took its place.

Source: The Wire China

Some shipments went to Russian electronics wholesalers — which go on to resell the components — while others have gone to telecom companies and GPS tracking companies. In November and December, the vast majority of shipments from Wynn Electronics went to PERCo, a security equipment manufacturer based in Saint Petersburg. PERCo, which did not respond to requests for comment, has taken part in exhibitions linked to the Russian military, but it is not clear what the company used the Wynn Electronics components for.

Two of the brands prominently advertised on the Winninc-AOOK websites are Texas Instruments and Analog Devices, which are both Nasdaq-listed U.S. semiconductor giants. They are also the companies behind one quarter of the chips found in Russian weapon systems analyzed by RUSI.

In a statement to The Wire, Texas Instruments said the company “stopped sales to Russia and Belarus at the end of February 2022, and we no longer support sales there. Texas Instruments complies with applicable laws and regulations in the countries where we operate. We do not support or condone the use of our products in applications for which they weren’t designed.”

Analog Devices did not respond to requests for comment.

Firms like Texas Instruments keep track of companies listed on the U.S. Entity List and are required to do due diligence on their customers and the end users of their products. But it may be difficult for them to know about the broader Winninc-AOOK network, and the screening process becomes harder when products are shipped through multiple intermediaries. Import Genius data does not show any direct exports from the U.S. to the Winninc-AOOK network, which suggests that goods from the U.S. firms may have been resold multiple times or produced outside of the United States.

Many of the global companies whose products were being sold by the Winninc-AOOK network told The Wire that they had no direct distributor relationship with any of the firms. Many of the firms also emphasized that they have reinforced their due diligence and sanctions compliance programs in the wake of the Ukraine invasion.

Partly due to the vast scale of China’s chip trade — it is the single largest chip market, accounting for more than a third of all global sales — most experts interviewed for this piece agree that the U.S. government would likely not punish the U.S. companies for their products ending up on Winninc and AOOK’s sites.

If I am looking at a product that ends up in Russia, almost always I can hone in on a red flag that should have been followed up on. And what is key [for these companies] is to really scrutinize carefully any exports to China.

“Companies have the duty to have compliance systems in place to look for red flags, but you can’t legally blame a company for activity three layers down,”says Kevin Wolf, a former official at the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), which controls the Entity List, and now a partner at the law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld. “For example, you don’t hold Ford liable if you are exceeding the speed limit.”

But, legality aside, the U.S. firms likely do not want to be aiding Russian troops, and the U.S. government has increasingly attempted to bring the private sector into its efforts. In March, the Commerce Department and Treasury Department released a notice to companies detailing compliance tips, particularly targeting third party intermediaries reselling goods to Russia. The agencies single out the use of shell companies as one red flag, for example, as well as using “addresses common to multiple closely-held corporate entities” and “a customer’s reluctance to share information about the end use of a product.”

Source: RUSI report, chip industry analysts

“This is all about running a competent compliance operation,” says Ryan Fayhee, who runs the sanctions, export controls and anti-money laundering practice group at the law firm Hughes Hubbard & Reed.

“[These companies] have to keep a lookout for any red flags. If I am looking at a product that ends up in Russia, almost always I can hone in on a red flag that should have been followed up on. And what is key [for these companies] is to really scrutinize carefully any exports to China.”

‘ENFORCEMENT AND COORDINATION’

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China had developed something of a reputation for helping its allies evade Western sanctions.

Chinese companies have been accused of facilitating coal trade with North Korea, for example, and transporting Iranian oil. In many of these cases, Chinese companies use mazes of front companies in various jurisdictions to cover their tracks. Just last month, the Treasury Department leveled sanctions against a Chinese network for providing components to Iranian drone manufacturers. The network set up a front company in Hong Kong to engage in millions of dollars of transactions.

“There is a long history of dropping a company and opening a new one. It is a very commonly used scheme,” says Fayhee, from Hughes Hubbard. “China is opaque, it is hard to do due diligence there.”

China is a hotbed of this activity due to a perfect storm of factors. Namely, its domestic manufacturing capability is so vast that it is difficult to keep track of legitimate versus illegitimate industries; Chinese politicians reject the validity of U.S. sanctions; and Chinese companies that do not significantly rely on the Western market do not fear falling afoul of U.S. laws.

In the face of this storm, Wolf says that BIS, at the Commerce Department, can only adapt and evolve as new information emerges. “Export controls have never been and never will be perfect,” he says. “The [Entity] list is constantly evolving as information evolves, including from reporters. The answer here is enforcement and coordination.”

That job of enforcement and coordination is only getting harder. Over the last year, the U.S. government has expanded its use of export controls against both China and Russia — around 150 Chinese companies have been added to the Entity list since the beginning of the Biden administration, according to data compiled by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), and about 450 Russian and Belarusian entities have been placed on the Entity List since the Ukraine invasion.

Source: The Wire China

To keep up with these sweeping controls, agencies have had to ramp up enforcement. In February, the Justice Department and Commerce Department launched a joint task force to ensure compliance with export controls and target specific illicit actors obtaining access to military technology. And in March, the Justice Department announced the addition of 25 new prosecutors focused on sanctions evasion and export control violations, as well as the first-ever chief counsel for corporate enforcement.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Lisa Monaco, the U.S. deputy attorney general, said in a March speech, turned sanctions into “the new FCPA” — referring to the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which prohibits U.S. individuals from bribing foreign officials for their business interests.

The invasion, Monaco said, “sparked a global response from governments and companies alike, and it elevated the importance of sanctions and export control enforcement. What was once a technical area of concern for select businesses should now be at the top of every company’s risk compliance chart.”

Enforcement is still a tall task, however. BIS, for instance, has around 550 staff members whose job it is to research companies all over the world, and to catch networks of companies like Winninc-AOOK that set up new companies with different names and websites. A recent Center for Strategic and International Studies report argues that the bureau is significantly under-resourced and advocated for expanding the BIS budget by $44 million dollars annually — a 23 percent boost to its 2023 budget. The increase would enable the office to hire more analysts as well as procure “modern, data-driven digital technologies” instead of “Google searches and Microsoft Excel,” which the report states BIS analysts typically use.

Apart from stepping up enforcement, however, the U.S. government could also decide to increase the severity of its sanctions. One way to do this would be through the Treasury Department’s Specially Designated Nationals And Blocked Persons (SDN) list — which essentially cuts companies or individuals off from the American financial system entirely and is considered a death blow for most companies.

OFAC’s sanctions and SDN list search engine.

While the Entity List sanctions only apply to the named firm, the SDN list applies to subsidiaries of sanctioned companies, which helps more holistically target bad actors. Plus, if an SDN-listed individual attempted to start a new company, it would automatically be listed as well.4

“If you’re using a tool, and you’re still seeing the problematic behavior, you do have to consider using a harsher tool,” says Emily Kilcrease, a senior fellow at CNAS and former U.S. Trade Representative official. She points out that Iran provides an interesting precedent: “It got to a certain point with Iran that we broke the seal a little bit in terms of doing SDN listings,” she says. “Are we now at that point with China?”

While the SDN list could more effectively target a network like the Winninc-AOOK companies, Wolf cautions that there are long term consequences of breaking this seal.

“SDN listings are like antibiotics. If used judiciously, they work well. But if you overuse antibiotics too much, they become ineffective,” he says, adding that Chinese companies could over time turn away from the U.S. financial system, thus lessening the impact of the SDN list.

If you are a Chinese company, the broader U.S., Europe, Asian market is so much more valuable. If you were forced to choose, it would not be a hard choice.

Regardless of the specific list used, however, the goal of all sanctions is to change the incentive structure for companies, which is far easier than changing the incentives of governments. When it comes to changing Winninc-AOOK’s incentives, Matthew Klein, an economics writer who has been tracking trade with Russia says, this shouldn’t be too hard: Russia is not a big market in the first place.

“If you are a Chinese company, the broader U.S., Europe, Asian market is so much more valuable,” says Klein. “If you were forced to choose, it would not be a hard choice.”

For now, though, the broader Winninc-AOOK network doesn’t seem like they are being forced to choose at all. In fact, the companies even seem to be expanding: Last month, one of the companies posted a job opening for “Foreign Trade Director.” When hiring new employees, another of the websites explains, the company looks for “dedicated professionals that actively push back the boundaries beyond what would normally be expected.”

Perhaps this time, however, they are pushing the boundaries a bit too far.