#1. You may be looking, but you are not observing.

You may be looking, but you are not observing.

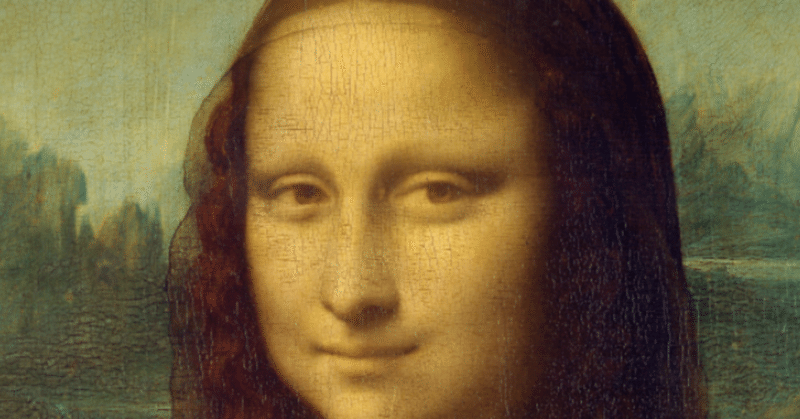

Now, please take a look at the following paintings (figures).

You know the Mona Lisa, don't you?

Don't say, "I know, I know, I know."

Art historical information about the artist and the work can be easily found on the Internet. However, without looking at the painting, you can ask questions such as,

"What is painted on each side of the figure? or

"Which hand is in front?" or

"Which hand is in front and how are they crossed?"

"How are the hands crossed?"

Our eyes seem to see, but we do not observe. In other words, our eyes are "lazy," meaning that once they see a rough outline or coloring and recognize it as the Mona Lisa, they "move on" to the next object of interest and do not look at any more details or take the time to pay attention to it.

We are taught that observation and listening are essential in medical care in medical school. On the other hand, they rarely take the time to learn how to do these specific things, and it is perceived as something that can be naturally cultivated through clinical experience. Similarly, the "ability to solve problems" is thoroughly taught, but there are basic assumptions, and unspoken understandings in examination questions, such as "All information not stated in the question text is correct and does not affect the answer," and "Information stated in the question text is an absolute and undeniable 'fact' that cannot be questioned.

On the other hand, in actual clinical practice, there is no guarantee that the information seen or heard is correct, and it is not always possible to find a solution with only the information at hand. In the first place, information itself must be collected from the field by the medical staff themselves and then selected and utilized by them.

The Great Potential of Art

So what is the relationship between medicine and art? Traditionally, art has been thought to have little connection with other fields. However, wouldn't it be exciting to think that by using art as a subject matter, we may be able to develop observation skills, verbalization skills, dialogue skills, and even sensitivity and aesthetic sensibilities that have not been taught in medical school classes and instruction?

Art is the crystallization of a tremendous amount of accumulated experience and information. The art we see has straddled multiple eras, has been viewed, reasoned about, and analyzed by countless people, and has been carefully selected. It is precise because there are no correct interpretations of art that we are free to carefully observe, interpret, deduce, and weave stories about even the most sensitive topics, such as race, status, facial expression, clothing, and body shape, which we would normally find difficult to deal with.

Today, we have smartphones at our fingertips, and we have developed the habit of immediately looking things up if we don't understand something. As a result, we have fewer and fewer opportunities to fully utilize all of our senses to look at the object in front of us without prior knowledge or the interpretation and opinions of others. Art is the perfect catalyst to restore our ability to observe and think independently.

Let us once again stand in front of the Mona Lisa and observe it with an open mind. Open your eyes, focus on the work, and prepare yourself to miss any information in the painting. You will soon notice details in the image that you have not seen a thousand times before.

Over the remaining 11 articles in this series, we will broadly explore the possibilities of art in medical education. We aim to sharpen your observational and interactive skills as the series progresses. We look forward to seeing you there.

from

まだまだコンテンツも未熟ですが応援して頂けるとすっごい励みになります!