息抜き用【上司のワーカホリズムが仕事の負荷と関係性の対立による情緒的消耗を介して部下の退職意図に影響を及ぼす】The crossover effects of supervisos' workaholism on subordinates' turnover intention: the mediating role of two types of job demands and emotional exhaustion

概要

ワーカホリックについて多くのk年休が行われてきたが、特に組織におけるクロスオーバー効果 (持ち越し効果) はあまり明らかにsれいない。

本研究では、バーンアウトに対する仕事の要求-資源モデルと資源の保全理論 (conservation of resources theory) に基づいて、2種類の仕事要求を通じて上司のワーカホリズムが部下の退職意思および情緒的消耗に及ぼす影響を明らかにする

その結果、上司のワーカホリズムは仕事量の増大と関係性の対立の増加を通じて部下の退職意思を促進することが示された

本研究は、ワーカホリズムの影響を自己から他者、そして組織的影響へと拡張した点で意義がある

(気やすめだが非常によい文献

(離職の意思は強度な心理的な負荷をもたらし、実際に影響があれば自殺のリスクを高める

(その一端が上司のワーカホリズムにも存在することは興味深い

(ぜひ自殺の予防・防止に取り組むものは自らをもって参考にされたい

問題と目的

ワーカホリズムと心身の健康に関する研究は数多く行われてきたが、それは対象者自身のものである

他者の視点特にスーパーバイザーのワーカーホリズムが同僚や部下に及ぼす影響はほどんど検証されていない

本研究では、JDR/CORモデルに基づき、スーパーバイザーのワーカホリズムは、仕事の負担及び関係性の対立を通じて部下の退職意思を高めるとの仮説をたてた

また、仕事の負荷が情緒的消耗を通じて退職意図を高めることは先行研究で知られていることから、2経路が情緒的消耗を促進して退職意図を高める仮説を立てた

スーパーバイザーのワーカホリズムと部下の情緒的消耗

ワーカホリックの仕事と家族の領域における研究は、ワーカホリックがspillover-crossoverプロセスを通じて家族に悪影響を及ぼすことを示した (Robinson, 2001)

ワーカホリズムの当事者のパートナーは関係満足度が低下し (Bakker, 2009)、別居が増加し (Robinson et al., 2001)、子どもの抑うつレベルが増加し (Robinson & Kelly, 1998)、情緒・行動の問題が増加する (Shimazu et al., 2020)

(我が国の労働安全衛生にかかるグループの研究も登場した

(ワーカホリズムは家族を不幸にする要因であることがわかる

ワーカホリックなリーダーの部下は常に仕事のことを考えるよう暗黙に要求される(Clark et al., 2016)

上司と似た行動をすると組織内で称賛を得られるため部下の言動は上司と似る傾向がある(Ambrose, Schminke ' Mayer, 2013; Tucker et al., 2010)

したがって上司の情緒的消耗は部下のバーンアウトにつながる (Sonnentag, Kuttler & Fritz, 2010)

仕事の負荷のメディエータの役割

仕事の負荷は仕事量と困難さで定義される

上司の仕事時間と部下の仕事時間には正の相関があり (Zhang & Seo, 2018)、

ワーカホリックな人は多くの時間を仕事にさくがしばしば非効率である (Porter, 2001)

ワーカホリックな人はしばしば簡単な課題に多くの時間を費やす (Naughton, 1987)

ワーカホリックな人はしばしば柔軟性に欠ける (Porter, 1996)

障害となる (不必要な) 仕事の要求を課されたものはバーンアウトしやすくなる (Li et al., 2020)

したがって、ワーカホリックな上司によって不必要な仕事の要求を課された部下は情緒的に消耗して退職意図を媒介すると予想される

関係性の対立のメディエータの役割

ワーカホリックなものは関係性の対立を引き起こしやすい (Ng et al., 2007)

ワーカホリックなものは自分と比較して他者を一生懸命働いていないと評価し (Harpaz & Snir, 2003)、他者を信頼しない (Porter, 1996; Mudrack & Naughton, 2001)

ワーカホリックなものは同僚に批判的・軽蔑的で (Harpaz & Snir, 2003)、攻撃的である (Scott et al., 1997)

ワーカホリックなものは自分を過大視して同僚や部下を見下しているにもかかわらず、しばしば優柔不断になる (Chonko, 1983)

ワーカホリックな上司は関係性を無視する傾向があり (Porter, 2001; McMillan et al., 2004)

不安や怒りなどネガティブな感情を他者に向ける傾向がある (Spence & Robbins, 1992; Ng et al., 2007)

ワーカホリズムはインシビリティとも関連がある (Lanzo et al., 2016)

したがって、部下と対人関係上の問題を生じるのは当然だといえる

スーパーバイザとの対人関係の問題を経験した部下は上司をネガティブに評価するが、組織の上下関係からその感情を表現せず、代わりに感情労働を体験する (Carlson et al., 2012; Wu & Hu, 2013)

したがって、その後は情緒的消耗から退職意思へとつながる

(感情労働について調べたことがなかった

(それより、ワーカホリズムな上司が部下の心身を通じて退職に向かわせる影響は、本気で自殺を防ぎたいものは、学びとするべきだろう

退職意思につながる情緒的消耗

COR theory (Conservation of resources theory: Hobfoll, 1989)は、個人が資源の安定・維持を行おうとする傾向を指摘している

したがって、より資源が枯渇するのを防ぐために個人は退職を選択する場合がある (Wright & Cropanzano, 1988; Zhang et al., 2019)

実際、情緒的消耗したものは回避や撤退のコーピングを用いる傾向が強まり (Leiter, 1991)、退職へとつながる

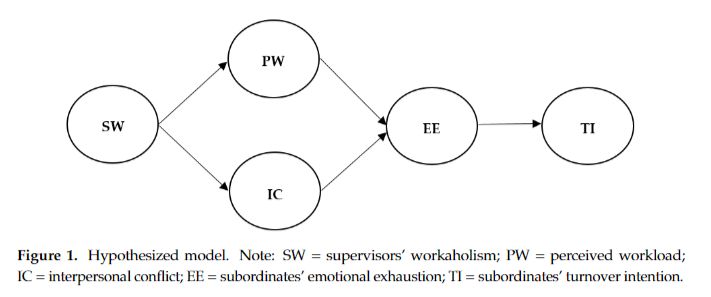

モデル

仮説1:

上司のワーカホリズムが部下の情緒的消耗を促す関係を、知覚された仕事の負荷がメディエートする

仮説2:

上司のワーカホリズムが部下の情緒的消耗を促す関係を、関係性の対立がメディエートする

仮説3:

情緒的な消耗は退職意図を促進する

仮説4:

上司のワーカホリズムと部下の退職意図は知覚された仕事の負荷と情緒的消耗によってよって完全にメディエートされる

仮説5:

上司のワーカホリズムと部下の退職意図は関係性の対立と情緒的消耗によって完全にメディエートされる

方法

対象者と手続き

対象者300名 (女性56.3%、平均年齢35.5歳、22-60歳、現在の職場で1年以上勤務、テニュア平均5.74年)

測定内容

①ワーカホリズム (Shaufeli et al., 2009)

(Shaufeliとのワーカホリズム研究に島津さんが絡んでいた)

②知覚された仕事の負荷 (Spector & Jex, 1998)

知覚された仕事の負荷を測定する、5項目5件法のリッカート尺度 (alpha = .77)

例:How often do you have to do more work than you can do well?

③関係性の対立 (Jehn, 1995)

関係性の対立を測定する、8項目、7件法のリッカート尺度

4項目ずつ、課題の対立と関係性の対立を測定するもの (alpha=.92,.90, respectively)

例:How much conflict about the work you do is there with your supervisor?

例:How much are personality conflicts evident with your supervisor?

確認的因子分析により、2因子構造が確認されている

④情緒的消耗 (Maslach et al., 2001)

情緒的消耗を測定する5項目5件法のリッカート尺度 (alpha=.89)

例:I feel emotionally drained by my work

⑤退職意図 (Lee et al., 2008)

以下2項目の5件法 (strongly disagree-strongly agree, alpha=.86)

I often think of changing my job

I plan to look for a new job within the next 1 year

⑥制御変数

年齢、性別、テニュア、職業タイプ (manufacturing, clerical, sales, administration, service, research, other)

分析

各尺度の確認的因子分析

のちに構造方程式モデルの95%バイアスコレクテッド信頼区間の推定 (5000 bootstrapped samples; Nevitt & Hancock, 2001)

結果

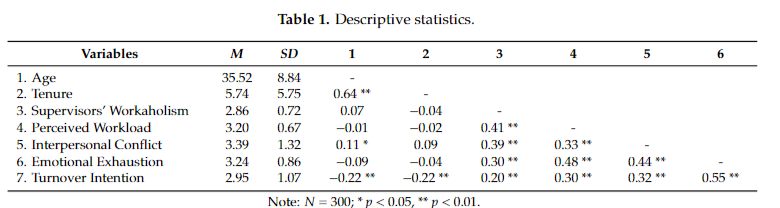

記述統計

スーパーバイザーのワーカホリズムが、メディエータとアウトカムに相関している

確認的因子分析

測定内容を5因子モデルで分析し、潜在的oneファクターも出るとの比較から、5因子モデルを確認した

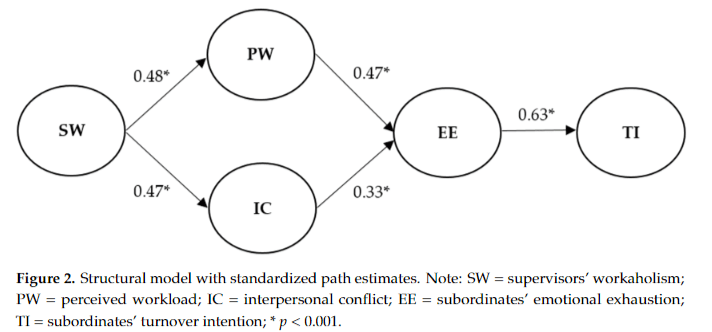

構造方程式モデルによるモデル検証

スーパバイザーのワーカホリズムは、情緒的消耗及び退職意図に直接影響を及ぼさず、情緒的消耗及び関係性の対立も直接退職意図に影響しなかった

したがって、完全媒介モデルの検証を行い、それぞれ適合性を示唆する指標を得た

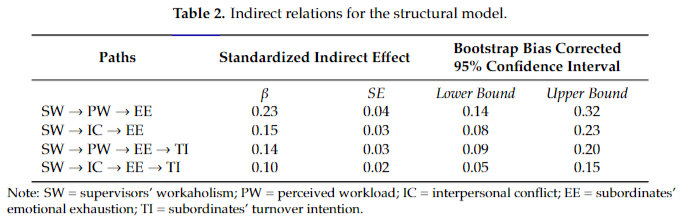

媒介効果の検証

スーパーバイザー・ワーカホリズムは、仕事の負荷を通じて情緒的消耗に影響を及ぼす (beta=.23)

スーパーバイザー・ワーカホリズムは、関係性の対立を通じて情緒的消耗に影響を及ぼす(beta=.15)

スーパーバイザー・ワーカホリズムは、仕事の負荷からの情緒的消耗を通じて退職意図に影響を及ぼす (beta=.14)

スーパーバイザー・ワーカホリズムは、関係性の対立からの情緒的消耗を通じて退職意図に影響を及ぼす (beta=.10)

文献

Ambrose, M.L.; Schminke, M.; Mayer, D.M. Trickle-down effects of supervisor perceptions of interactional justice: A moderated mediation approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 678–689. [

Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Burke, R. Workaholism and relationship quality: A spillover-crossover perspective. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 23–33.

Carlson, D.; Ferguson, M.; Hunter, E.; Whitten, D. Abusive supervision and work–family conflict: The path through emotional labor and burnout. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 849–859.;

Chonko, L.B. Job involvement as obsession-compulsion: Some preliminary empirical findings. Psychol. Rep. 1983, 53, 1191–1197.

Clark, M.A.; Stevens, G.W.; Michel, J.S.; Zimmerman, L. Workaholism among Leaders: Implications for their own and their followers’ well-being. In The Role of Leadership in Occupational Stress; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2016; Volume 14, pp. 1–31.

Harpaz, I.; Snir, R. Workaholism: Its definition and nature. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 291–319.

Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524.

Jehn, K.A. A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Admin. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 256–282.

Kim N, Kang YJ, Choi J, Sohn YW. The Crossover Effects of Supervisors' Workaholism on Subordinates' Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Two Types of Job Demands and Emotional Exhaustion. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Oct 23;17(21):7742.

Lanzo, L.; Aziz, S.; Wuensch, K. Workaholism and incivility: Stress and psychological capital’s role. Int. J. Work. Health Manag. 2016, 9, 165–183.

Lee, S.H.; Kim, M.S.; Park, S.K. A test of work-to-family conflict mediation hypothesis for effects of family friendly management on organizational commitment and turnover intention. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 21, 383–410

Leiter, M.P. Coping patterns as predictors of burnout: The function of control and escapist coping patterns. J. Organ. Behav. 1991, 12, 123–144.

Li, P.; Taris, T.W.; Peeters, M.C. Challenge and hindrance appraisals of job demands: One man’s meat, another man’s poison? Anxiety Stress Coping 2020, 33, 31–46.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 397-422.

McMillan, L.H.; O’driscoll, M.P.; Brady, E.C. The impact of workaholism on personal relationships. Br. J. Guid. Counsel. 2004, 32, 171–186.

Mudrack, P.E.; Naughton, T.J. The assessment of workaholism as behavioral tendencies: Scale development and preliminary empirical testing. Int. J. Str. Manag. 2001, 8, 93–111

Naughton, T.J. A conceptual view of workaholism and implications for career counseling and research. Career Develop. Q. 1987, 35, 180–187

Nevitt, J.; Hancock, G.R. Performance of bootstrapping approaches to model test statistics and parameter standard error estimation in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2001, 8, 353–377.

Ng, T.W.; Sorensen, K.L.; Feldman, D.C. Dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of workaholism: A conceptual integration and extension. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2007, 28, 111–136

Porter, G. Organizational impact of workaholism: Suggestions for researching the negative outcomes of excessive work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 70–84.

Porter, G. (2001). Workaholic tendencies and the high potential for stress among co-workers. International Journal of Stress Management, 8, 147-164.

Robinson, B.E. Workaholism and family functioning: A profile of familial relationships, psychological outcomes, and research considerations. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2001, 23, 123–135.

Robinson, B.E.; Carroll, J.J.; Flowers, C. Marital estrangement, positive affect, and locus of control among spouses of workaholics and spouses of nonworkaholics: A national study. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2001, 29, 397–410.

Robinson, B.E.; Kelley, L. Adult children of workaholics: Self-concept, anxiety, depression, and locus of control. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 1998, 26, 223–238.

Scott, K.S.; Moore, K.S.; Miceli, M.P. An exploration of the meaning and consequences of workaholism. Hum. Relat. 1997, 50, 287–314.

Schaufeli, W.B.; Shimazu, A.; Taris, T.W. Being driven to work excessively hard: The evaluation of a two-factor measure of workaholism in the Netherlands and Japan. Cross Cult. Res. 2009, 43, 320–348

Shimazu, A., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., Fujiwara, T., Iwata, N., Shimada, K., ... & Kawakami, N. (2020). Workaholism, work engagement and child well-being: A test of the spillover-crossover model. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(17), 6213.

Sonnentag, S.; Kuttler, I.; Fritz, C. Job stressors, emotional exhaustion, and need for recovery: A multi-source study on the benefits of psychological detachment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 355–365.

Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (1998). Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. Journal of occupational health psychology, 3(4), 356.

Spence, J.T.; Robbins, A.S. Workaholism: Definition, measurement, and preliminary results. J. Personal. Assess. 1992, 58, 160–178

Tucker, S.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; McEvoy, M. Transformational leadership and childrens’ aggression in team settings: A short-term longitudinal study. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 389–399.

Wu, T.Y.; Hu, C. Abusive supervision and subordinate emotional labor: The moderating role of openness personality. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 956–970.

Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R. Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 486–493.

Zhang, L.; Seo, J. Held captive in the office: An investigation into long working hours among Korean employees. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2018, 29, 1231–1256.

Zhang, L.; Fan, C.; Deng, Y.; Lam, C.F.; Hu, E.; Wang, L. Exploring the interpersonal determinants of job embeddedness and voluntary turnover: A conservation of resources perspective. Hum. Res. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 413–432.

コメント

(区間の重複があるため、媒介効果の優劣は認められない)

(また、媒介を重ねると効果がうすまる)

(情緒的消耗感が退職意思を強く予測することは頭に入れておく

(また、途中でサブリミナル的に理論が登場したが、あまり役に立っていないことも指摘しておく

(ただし、感情労働については調べる

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?