読書ノート:Part III/Chapter 9 of THE PSYCHOLOGY OF TOTALITARIANISM

はじめに

このノートは、The Psychology of Totalitarianism(Mattias Desmet著)を読み、重要と思われた部分を抜き出して記録したものです。ノートは、章単位の構成となっています。他章のノートを参照する場合、各ノート末の「全体校正」のリンクを参照してください。

このノートは、一読者としての印象を部分的に抜き出たものです。私の意見・感想は含まれていません。しかし、部分的な抜き出しなので、正しい内容を反映していないかもしれません。また、本文での引用情報も含まれていません。従って、本書を正しく理解するためには、ぜひ原文をお読みください。

(しかし、いつの間にか、ほぼ全文を訳し始めているのですが。。。。抜き出すより、その方が楽だったので。。。。)

このノートの目的は、自分としての理解の整理ですが、もし、本書の興味の一助になれば嬉しいです。

Part III: Beyond the Mechanistic Worldview /

Chapter 9: The Dead versus the Living Universe

The following is broadly the causal reasoning we have presented in this book: The mechanistic ideology has put more and more individuals into a state of social isolation, unsettled by a lack of meaning, free-floating anxiety and uneasiness, as well as latent frustration and aggression. These conditions led to large-scale and long-lasting mass formation, and this mass formation in turn led to the emergence of totalitarian state systems.

以下は、本書が提示した、おおまかな因果関係の推論です。人々は、機械論的イデオロギーにより社会的孤立に追い込まれ、意味の欠如・漠然とした不安と心配、潜在的な不満・攻撃性により不安定化します。この状況が大規模かつ長期的な大衆形成を生み、この大衆形成が全体主義国家システムを生み出します。

Therefore, mass formation and totalitarianism are in fact symptoms of the mechanistic ideology. Just like an individual physical or psychological symptom, these social symptoms signal an underlying problem: In this case, that a large proportion of the population feels socially isolated and suffers from intense experiences of anxiety and meaninglessness. And just like individual symptoms, they generate a disease gain. For example, they transform the experiences of social isolation and fear into an illusion of connectedness. And as with individual symptoms, they generate this disease gain while failing to solve the underlying problem itself.

従って、大衆形成と全体主義は、機械論的イデオロギーによる症状です。個人の身体的・心理的症状と同様に、これらの社会的症状の根底に問題があることを示しています。この場合、人口の大部分が、社会的に孤立していると感じ、不安と無意味さに苦しんでいます。そして、疾病利得を得ます。例えば、彼らは、社会的孤立と恐怖の経験を「つながりの幻想」(an illusion of connectedness)に変換します。そして、個々の症状と同様に、根底にある問題自体を解決できず、この病気の増加を引き起こします.

For this reason, we need an analysis of the underlying problem—that is, the cause of the symptom, namely the mechanistic ideology. Societies are primarily besieged by ideas. The most fundamental change that we as a society have to aim for is not a change in practical terms but a change in consciousness. In the first part of this book, we examined the psychological problems caused by the mechanistic ideology; in the final part, we will examine how we can transcend this ideology. In this chapter, we will reflect upon one of the core characteristics of the mechanistic ideology. This ideology sees the universe as a logically knowable, predictable, controllable, and undirected mechanical process. And above all, it sees the universe as a dead and meaningless given, as the blind, mechanistic interaction between dead, elementary particles. While such a view of the world and matter imposes itself as the only scientifically valid view, a thorough examination teaches us that, from a scientific point of view, this world view is actually outdated.

このため、根本的な問題、つまり症状の原因である、機械論的イデオロギーの分析が必要です。社会は、主に思想(幻想?)に悩まされています。私たちが、社会として目指すべき最も根本的な変化は、現実的な変化ではなく、意識の変化です。この本の前半では、機械論的イデオロギーによって引き起こされる心理的問題を検討しました。最終章では、このイデオロギーを超越する方法を検討します。本章では、機械論的イデオロギーの核となる特徴の 1 つについて考察します。このイデオロギーは、宇宙を、論理的に認識可能で、予測可能で、制御可能で、無目的な機械的プロセスと見なしています。そして何よりも、このイデオロギーは、宇宙を無生命・無意味なものとして決められちた存在(given)としみなし、無生命な素粒子間の盲目的な機械的相互作用として見ています。このイデオロギーは、このような世界観と物質観を、科学的に有効な唯一の見解として、我々に押し付けます。しかし、徹底的に調べてみると、科学的な観点からは、この世界観は実際には時代遅れであることがわかります。

* * *

The mechanistic worldview is, in fact, as old as man himself, or at least, it was already present in what we usually consider the early days of Western civilization. In the era of the ancient Greeks, about 400 BCE, atomists such as Leucippus and Democritus were already defending the idea that the universe, in its entirety, was essentially a collection of mechanically interacting material particles. Those particles were already called atoms, which means “indivisible” or, more literally, “unsliceable” (atomos).

実際、機械的な世界観は、人類と同じくらい古いか、少なくとも、西洋文明の初期の頃に「当たり前な考え方」として存在していました。紀元前 400 年頃の古代ギリシャ時代、レウキッポスやデモクリトスなどの原子論者は、宇宙全体が本質的に機械的に相互作用する物質粒子の集まりである考えていました。これらの粒子はすでにアトムと呼ばれていました。これは、「分割できない」、または、文字通り「スライスできない」(atomos) という意味です。

It was not until the Enlightenment, however, that mechanistic thinking became dominant and provided the only remaining Grand Narrative of Western culture. As we discussed in chapter 1, this ideology even furnished a kind of creation myth: Everything starts with a big bang that sets the machine of the universe in motion and, through a series of mechanistic effects, produces first a series of inorganic elements and subsequently also living beings. Within this reasoning, the world is a dead mechanistic process, an enormous chain reaction of collisions of elementary particles that continues endlessly, without purpose or direction, and somewhere along the way, randomly produces life and mankind.

しかし、啓蒙時代になるまで、機械論的思考は、西洋における支配的な「壮大な物語」(Grand Narrative)にはなりませんでした。第 1 章で説明したように、このイデオロギーは一種の創造神話を生み出しました。すべては、宇宙の機械を動かすビッグバンから始まり、一連の機械的効果を通じて、最初に一連の無機要素を生成し、続いて生物も生成します。この推論の中で、世界は無生命な機械的プロセスであり、素粒子の衝突の巨大な連鎖反応であり、目的も方向もなく無限に続き、途中のどこかで生命と人類がランダムに生成されます。

This entire process is seen as strictly predictable. The French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace expressed this in perhaps the most direct way:

このプロセス全体は、厳密に予測可能であると見なされます。フランスの数学者ピエール=シモン・ラプラスは、おそらく最も直接的に、この世界観を表現しました。

We ought then to regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its anterior state and as the cause of the one which is to follow. Given for one instant an intelligence which could comprehend all the forces by which nature is animated and the respective situation of the beings who compose it […] it would embrace in the same formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the lightest atom; for it, nothing could be uncertain and the future, as the past, would be present to its eyes.

(ラプラスの主張)

宇宙の現在の状態は、その前の状態の結果であり、後に続く状態の原因であると見なすべきです。自然を活性化するすべての力と、それを構成する存在のそれぞれの状況を理解できる知性が一瞬与えられたなら、(途中省略)それは、宇宙の最大の物体の動きと最も軽い原子の動きを同じ式に包含します。不確実なものは何もなく、未来は過去と同じように目の前にあります。

Most philosophers have considered such a worldview to be naive. Bertrand Russell, for example, argued in his Russell’s paradox that there can never be an entity, however much computing power it has, that can have complete knowledge. Such an entity would also have to have a complete knowledge of itself, and also a complete knowledge of itself as an entity possessing complete knowledge of itself, and so on to infinity. In the twentieth century, Werner Heisenberg also proved this concretely: One cannot speak of elementary particles in terms of certainty. The more accurately their position in time is determined, the more uncertain becomes their location in space. “Not only is the universe stranger than we think; it is stranger than we can think.” (See Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle.)

ほとんどの哲学者は、この様な世界観をナイーブだと考えてきました。たとえば、バートランド・ラッセルは、ラッセルのパラドックスの中で、どんなに計算能力が高くても、完全な知識を持つ実体は存在し得ないと主張しました。そのような実体自身は、完全な知識を持たねばなりません。そして、その完全な知識は、それを完全に処理する実体でなければなりません。これば無限に繰り返されます。20 世紀に、ヴェルナー ハイゼンベルグは、これを具体的に証明しました。素粒子を確実に語ることはできません。時間内の位置が正確に決定されるほど、空間内の位置は不確実になります。「宇宙は私たちが考えている以上に奇妙なだけではありません。私たちが考えることができる以上に奇妙なのです。」(ハイゼンベルグの不確定性原理を参照してください。)

These elementary building blocks of the universe—atoms—appeared to be both more complex and more elusive than previously thought. The more the researcher’s hand tried to close itself around them, the more they slipped through his fingers. Rather than the tiny, massive spheres envisioned by the ancient Greeks, twentieth-century physics showed them to be swirling, energetic systems, patterns of vibration rather than solid matter. Yes, in the final analysis, they even turned out not to be material phenomena at all but rather to belong to the order of consciousness. The great physicists of the twentieth century believed them to be mere thought-forms, mental phenomena that respond to the consciousness of researchers (as we shall discuss further in the chapter 10).

宇宙の基本構成要素である原子は、これまで考えられていたよりも複雑でとらえどころのないものに見えました。研究者の手がそれらの周りに近づこうとする程に、それらは彼の指をすり抜けました。20 世紀の物理学は、基本構成要素が、古代ギリシャ人が思い描いた小さくて重い球体や個体ではなく、渦巻くエネルギー システムや振動パターンであることを示しました。最終的な分析では、それらは物質的な現象ではなく、むしろ意識の秩序に属していることが判明しました。20 世紀の偉大な物理学者は、それらは単なる思考形態であり、研究者の意識に反応する心的現象であると信じていました (これについては第 10 章で詳しく説明します)。

We could of course delve deeper into the findings of quantum mechanics to further relativize the idea of a mechanistic universe. But the phenomena of which quantum mechanics speaks are situated in a dimension that most people will never have access to. Who will ever get a direct look at the subatomic world? In this respect, there is another field of science that offers better, more concrete perspectives, namely the complex and dynamic systems theory and the chaos theory. These theories deal with phenomena that everyone, in principle, can sensorily perceive and that illustrate the limitations of the mechanistic vision in an equally convincing way.

もちろん、量子力学の発見をさらに深く掘り下げて、機械論的宇宙のアイデアに反映させることもできます。しかし、量子力学が語る現象は、ほとんどの人がアクセスできない次元にあります。素粒子の世界を直接見られるのは誰でしょうか?より優れた、より具体的な視点を提供する別の科学分野があります。それは、複雑な動的システム理論とカオス理論です。これらの理論は、原理的に誰もが感覚的に知覚できる現象を扱い、説得力のある方法で機械的視覚の限界を説明しています。

* * *

When Benoit Mandelbrot—a brilliant mathematician, considered one of the founders of chaos theory—joined IBM, he was confronted with the problem of noise that interferes with computer signals transmitted over telephone lines. This noise occurred due to a series of external factors, such as humidity, irregularities in the material of the lines, and small electromagnetic disturbances that hampered signal transmission in an accidental and incalculable way. We can only assume that these factors acted in a random way and independently from one another and therefore, normally, there cannot be any consistency in the noise on the telephone lines.

ブノワ・マンデルブロート(カオス理論の創始者の 1 人と考えられている優秀な数学者)が IBM に入社したとき、電話回線を介して送信されるコンピューター信号を妨害するノイズの問題に直面しました。一連の外的要因(湿度、信号線の材質の不均一性、電磁気的な乱れ)に起因するノイズは、信号の伝達を、無限かつ偶発的に妨害します。これらの要素はランダムかつ独立に発生するとしか考えられないので、信号回線上のノイズに一貫性はありえないと考えられます。

Mandelbrot was not a person who believed what everyone else believed, however. He was bold enough to assume that there might be a pattern in the noise after all. “Just because it doesn’t make sense doesn’t mean it can’t exist,” he said. And he was correct. In the noise, he discovered a well-known mathematical pattern, known as Cantor dust. Anyone can easily reproduce this pattern by repeatedly dividing a line into three segments and omitting the middle segment each time.

しかし、マンデルブローは、他人が信じていることを信じる人ではありませんでした。最終的に、彼はノイズにパターンがあるかもしれないと、大胆に仮定しました。「説明できなことと、存在しないことは、別です」と彼は言いました。そして彼は正しかった。彼は、ノイズの中に、カントール塵(またはカントール集合と呼ぶ)として知られる有名な数学的パターンを発見しました。このパターンは、線を 3 つのセグメントに分割し、その都度中央のセグメントを省略することを繰り返すことで、誰でも簡単に再現できます。

The big question, of course, is the following: How is it possible that a series of random factors, manifesting independently, can lead to a regular pattern? How could it be that damage caused to a cable by, say, a screwdriver and the magnetic disturbances of a thunderstorm become part of the same pattern? It is as if all these accidental, mechanical disturbances are drawn into a stable and strictly mathematically ordered field in order to be stripped of any coincidence. James Gleick put it this way: “Life sucks order from a sea of disorder.” The noise on a telephone line seems to organize itself. In living organisms, we have—erroneously—come to consider this quality of selforganization to be normal. Living beings breathe air, and eat and drink, and all these disparate elements bring about the ordered pattern of their bodies. However, when this phenomenon manifests itself in the inorganic world, we perceive it as a perplexing phenomenon and contrary to the prevailing worldview (which it is).

もちろん、大きな問題は次のとおりです。独立して現れる一連のランダムな要因が、どのようにして規則的なパターンになるのでしょうか?例えば、どうすれば、ドライバーによるケーブルの損傷と、雷雨による磁気障害が同じパターンの一部になるのでしょうか?あたかも、これらすべての偶発的機械的外乱が、偶然の一致を取り除くために、厳密かつ数学的に順序付けられた場に引き込まれているかの様です。ジェイムス・グリックは次のように述べています。「人生は無秩序の海から秩序を吸い取る。」電話回線のノイズは、とても自然に整理されているように見えます。我々は、生物が自己組織化の能力を持っていることを、当たり前と考えるようになりました。生き物は、空気を呼吸し、飲み食いします。そして、取り込まれた様々な要素は、体内に秩序あるパターンを生み出します。しかし、この現象が無機的な世界に現れると、一般的な世界観に反するため、当惑します。

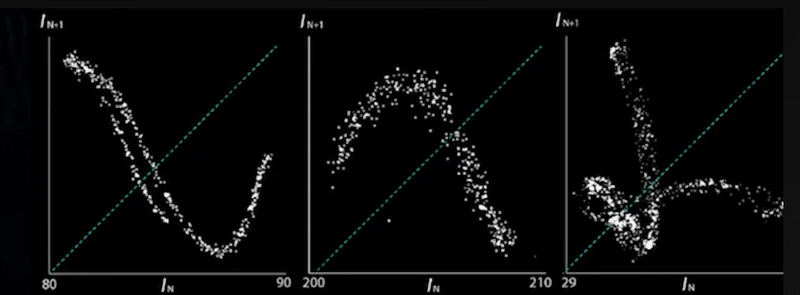

Another example is the regularity of water droplets, dripping from a faucet, as demonstrated by Robert Shaw. This is an example from everyday life, observable by anyone. A relatively simple mathematical procedure suffices to show that there is mathematical regularity in the lapse of time between the drops dripping down, which, when represented visually, produces beautiful organic patterns. In this case as well, we encounter the curious paradox that the moment a drop of water drips down is, on the one hand, caused by a series of disconnected, external factors—the surface tension of the water, the temperature, vibrations in the surrounding air, the texture of the faucet’s rim. But on the other hand, it seems to follow a strict pattern. The reason all these unrelated factors lead to a consistent pattern is difficult, even impossible, to explain within a mechanistic worldview. Obviously, this pattern can be disrupted by certain interferences—for example, by intentionally blocking the mouth of the faucet with your finger. However, after the cessation of this interference, where it is difficult to determine in which way it differs from the other external factors, the system returns to its spontaneous equilibrium and the pattern reinstates itself.

もう一つの例は、ロバート・ショウにより実証された、蛇口から滴る水滴の規則性です。これは日常生活の例であり、誰でも観察できます。比較的単純な数学的手順で、水滴が落ちる間隔の時間経過に数学的な規則性があることを示すことができます。これを視覚的に表現すると、美しい有機的なパターンが生成されます。この場合も、奇妙なパラドックスに遭遇します。水滴が落ちるのは、互いに独立した外部要因(水の表面張力、温度、周辺の振動、蛇口の材質)の結果です。しかし一方で、それは厳密なパターンに従っているようです。これらすべての無関係な要因が一貫したパターンにつながる理由を、機械的な世界観の中で説明するのは困難であり、不可能ですらあります。明らかに、このパターンは特定の干渉によって乱される可能性があります。例えば、蛇口の口を指で意図的に塞ぐなどです。しかし、この干渉が停止すると、(この干渉を他の外部要因と区別することが困難にも関わらう)システムは自然に平衡状態に戻り、パターンは元に戻ります。

UCLA Modeling Class: Mathematics for Life Sciences

19.4 Dripping Faucet 8 14 2019

余談だが、この映像はどうやって作っているのだろうか?

この先生が鏡写しの文字を書いているとは思えない。

Gleick had the following to say about it: “Those studying chaotic dynamics discovered that the disorderly behavior of simple systems acted as a creative (italics added) process. It generated complexity: richly organized patterns, sometimes stable and sometimes unstable, sometimes finite and sometimes infinite, but always with the fascination of living things.” Please, take note of the qualifications creative and living. This aspect of creation and life in matter was overlooked by the classical scientific approach.

グリックは、これに関して次のように語っています。「カオス力学を研究している人たちは、単純なシステムの無秩序な振る舞いが、創造的(ボールドを追加)なプロセスとして働くことを発見しました。それは複雑さを生み出します。時に安定し、時に不安定な、有限であり無限でもある、しかし常に生き物の魅力を備えた、豊かに組織化されたパターンです。」どうか、創造的(creative)と生命的(living)という修飾語句に注目してください。物質における創造と生命のこの側面は、古典的な科学的アプローチでは見落とされていました。

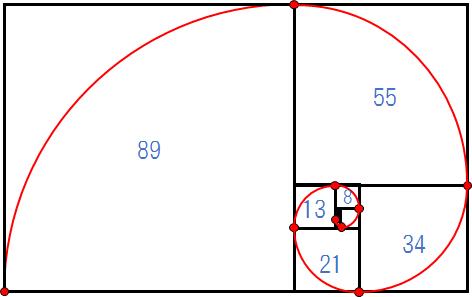

More or less in line with these examples, fractal theory (a subdomain of chaos theory) showed an unsuspected, mathematical determinacy of sets of natural forms, such as those of leaves, plants, trees, sea sponges, algae. The best-known examples are perhaps seashell patterns studied by Hans Meinhardt; the Mandelbrot set; and the spiral shapes determined by the Fibonacci sequence. This last determination is so simple that it is easily understandable, even to nonmathematicians. The Fibonacci sequence consists of a series of numbers that is obtained by starting with the numbers 0 and 1 and then continuing with a number that is the sum of the two previous numbers (so 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, etc.). This series of numbers determines the curves of a spiral that can be found everywhere in nature. Galileo’s famous statement in 1623 that “The book of nature is written in the language of mathematics” must be taken literally, it seems.

これらの例とほぼ同様に、フラクタル理論(カオス理論のサブドメイン)は、葉、植物、木、海綿、藻などの自然の形の集合に、思いもよらない数学的決定性があることを示しました。最もよく知られている例は、ハンス・マインハルトによって研究された貝殻の模様でしょう。例えば、マンデルブロー集合、フィボナッチ数列で決まる螺旋形などです。このフィボナッチ数列は、数学者でなくても容易に理解できるほど単純なものです。フィボナッチ数列は、0と1から始まり、前の2つの数の和になる数(つまり0、1、1、2、3、5、8など)を続けて得る数列です。この数字の羅列によって、自然界のどこにでも見られる螺旋の曲線が決まります。1623年にガリレオが言った「自然の本は数学の言葉で書かれている」という有名な言葉は、文字通りに受け取らざるを得ないようです。

「フィボナッチ数からつくる最も美しい螺旋 – 螺旋が使われている例は?」より引用

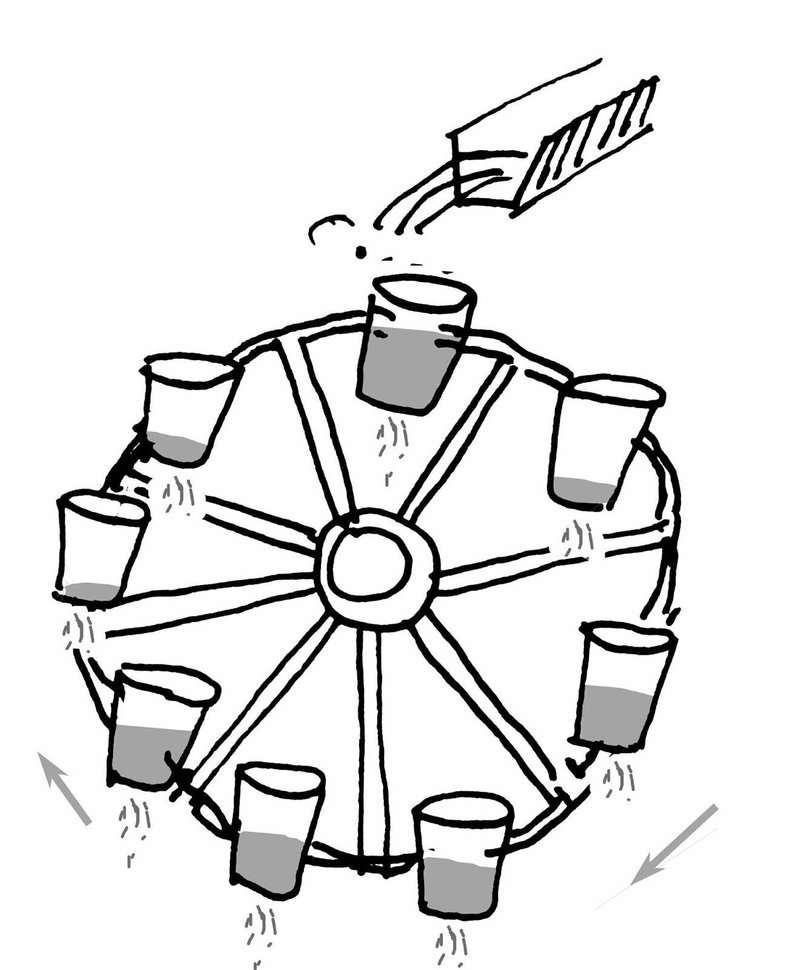

Let’s take a closer look at one example. Lorenz’s chaotic waterwheel is a mechanical device that makes movements that show direct similarities with the dynamics of convection patterns in liquid and gas. (See figure 9.1.) It was designed by MIT professor Willem Malkus in 1972 to illustrate the work of Edward Lorenz, a mathematician and meteorologist and one of the founders of chaos theory. It consists of a rotating wheel to which small buckets with a bottom hole are attached. At the top, there is a tap that provides water flow into the top bucket. At a very low influx, the wheel does not move, simply because the water flows out of the hole in the bottom of the bucket faster than it flows in. At a slightly higher influx, the bucket will fill up and the wheel will start to move, sometimes in one direction, sometimes in the other. Once the wheel has chosen a certain direction, the behavior of the wheel is regular and predictable and directly correlated with the influx of water: The greater the influx, the faster it turns.

その一例を詳しく見ましょう。ローレンツのカオス水車(またはMalkus waterwheel)は、液体や気体の対流パターンのダイナミックスと直接的に類似した動きをする機械装置です(図9.1参照)。これは、カオス理論の創始者の一人である数学者・気象学者エドワード・ローレンツの研究を説明するために、1972年にMITのウィレム・マルクス教授が設計したものです。回転する車輪に、底穴の開いた小さなバケツを取り付けたものす。上部には蛇口があり、上のバケツに水流が供給される。水の流入量が非常に少ないときは、バケツの底の穴から水が流れ出る速度が流入する速度よりも速いため、車輪は動きません。流入量が少し多くなると、バケツの水がいっぱいになり、車輪が動き出します。車輪がある方向を選ぶと、車輪の挙動は規則的で予測可能であり、水の流入量と直接的に相関しています。水の量が多ければ多いほど、車輪は速く回転します。

The Philosopher: Lorenz’s Water Wheelより引用

Chaos | Chapter 8 : Statistics - Lorenz' mill

If the influx exceeds a certain limit, however, a series of complex effects occur that cause the wheel to behave erratically. The top bucket initially fills to the brim, causing the wheel to turn at a high speed. But then, because of the high speed, the other buckets hardly get a chance to fill up as they pass by the top. This causes the wheel to slow down and possibly come to a temporary stop, whereupon it continues to rotate in the same direction, or sometimes in the opposite direction. This process is repeated with countless variations; the wheel sometimes moves quickly, sometimes slowly, sometimes in the same direction for a prolonged period of time, sometimes constantly changing direction. The irregularity in the chaotic phase was shown to be total in nature. This means that there is no (strictly) repeating pattern or repeating period in the wheel’s movements.

しかし、流入量がある限度を超えると、複雑な現象が次々と起こり、ホイールの挙動がおかしくなります。最初は一番上のバケツが満杯になり、車輪は高速で回転します。このため、他のバケツは、1番上を通過してしまうので、水が入りません。すると、車輪は減速し、場合によっては一時的に停止して、また同じ方向、あるいは逆方向に回転します。この過程が無限に繰り返され、車輪は速く動いたり、遅く動いたり、長時間同じ方向に動いたり、絶えず方向を変えたりします。カオス相の不規則性は、全体的なものであることが示されました。つまり、車輪の動きには(厳密には)繰り返しのパターンや繰り返しの周期が無いのです。

No matter how chaotic the movements appear, they surprisingly turned out to be strictly determined. They can be described by a mathematical model consisting of three iterative differential equations with three unknowns (which in themselves are actually a simplification of the much more complex Navier-Stokes convection equations). In conformity with the chaotic behavior of the wheel, the (endless) series of solutions of these equations shows no periodicity either. Or, in other words, there is no recurring pattern in the set of values of the unknowns generated by the equations. Therefore, the dynamics of the wheel closely resemble the structure of irrational numbers, such as pi, whose digits after the decimal point do not show any periodicity either. The qualification of such numbers as “irrational” primarily refers to the fact that such numbers cannot be written as a fraction, as a ratio. However, in laymen’s terms, “irrational” in the sense of not rational is not incorrect either. It is true that such numbers cannot be rationally envisaged. That makes them disruptive in a logically ordered, rational worldview. Hippasus (a follower of Pythagoras)—who is considered the person who discovered these irrational numbers—experienced this to his own detriment. Legend has it, he was on a ship with his brethren Pythagoreans and was promptly thrown overboard when he articulated his intuition that there exists something such as irrational numbers. This illustrates clearly: The limits of the ratio always lead initially to uncertainty, fear, and aggression.

一見無秩序に見えるこの運動は、意外にも厳密に決定されていることが判明しました。それは、3つの未知数(3つの未知数は、遥かに複雑なナビエ–ストークス方程式を単純化したものです)を持つ3つの常微分方程式(ordinary differential equationからなる数学的モデル(ローレンツ方程式)で記述することができます。車輪のカオス的な振る舞いと一致するように、これらの方程式の(無限の)解は周期性を示しません。言い換えれば、方程式が生成する値の集合には、繰り返されるパターンがありません。従って、車輪の力学は、円周率のように小数点以下の桁に周期性がない無理数の構造に酷似しています。このような数が「無理数」と呼ばれるのは、主に分数や比率で表現できないことを意味しています。しかし、素人目には、合理的でないという意味での「不合理」も間違いありません。確かに、このような数を合理的に予想することはできません。故に、論理的に整然とした合理的な世界観の中では、破壊的な存在となります。この無理数を発見したとされるヒッパソス(ピタゴラスの弟子)は、このことを身をもって体験しています。ピタゴラスと一緒に船に乗っていたとき、「無理数のようなものがある」と直感した彼は、すぐさま海に投げ出されたという伝説がある。このことは、はっきりと示しています。常に、比率の限界は、まず、不確実性・恐怖・攻撃性につながります。

The combination of chaotic behavior and determinism gives the waterwheel the fascinating property of “deterministic unpredictability.” It amounts to the following: Even with the waterwheel formulas at hand, it is not possible to predict, even only one second in advance, how it will behave. The reason for this is simple: To be able to predict how the waterwheel will behave in the future, you need to measure the wheel’s state of motion in the present and enter it into the formulas. But due to the nature of the wheel, even immeasurably small differences in the current state of motion can lead to radical differences in future behavior (in systems theory, this is called the property of “sensitivity to initial conditions”). Therefore, the wheel continues to shroud its future in mystery forever.

カオス的振る舞いと決定論の組合せることで、この水車に「決定論的予測不可能性」という素晴らしい特性が備わります。それは、次のとおりです:水車の公式を手にしても、それがどのような挙動を示すか、たとえ1秒前であっても予測することは不可能です。その理由は簡単です:水車が将来どのように動くかを予測するためには、現在の水車の状態を測定して、それを数式に入力する必要があります。しかし、水車の性質上、現在の運動状態の違いが、たとえ計り知れないほど小さくても、将来の挙動に根本的な違いをもたらします。(システム理論では、これを「初期条件に対する感度」と呼びます)。 そのため、車輪の挙動は、未来永劫に謎のままです。

What is most fascinating about the story of Lorenz’s waterwheel is this: At some point, Lorenz got the idea to plot the successive values of the three quantities in the equations on a three-dimensional orthogonal coordinate system, also called phase space in chaos theory. Curiously enough, it was not just a random nebula of points that appeared, as one would initially expect with a chaotically behaving system. What emerged was a very regular figure with striking aesthetic features, which has since been known as the Lorenz attractor (see figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2. The Lorenz attractor

ローレンツの水車の話で最も魅力的なのは、次の点です。ある時、ローレンツは、方程式に含まれる3つの数量の連続値を、カオス理論で位相空間と呼ばれる3次元直交座標系にプロットすることを思いつきました。すると不思議なことに、それは、カオス的に振る舞う系で予想されるような、ランダムな点の星雲ではありませんでした。そこに現れたのは、印象的な美しさを伴う規則的な図でした。以来、これはローレンツ・アトラクターとして知られています(図9.2参照)。

thinkeccel: The Lorenz Attractor Animation| Butterfly Effect| Lorenz System

As Gleick said, “Phase-space portraits of physical systems exposed patterns of motion that were invisible otherwise, as an infrared landscape photograph can reveal patterns and details that exist just beyond the reach of perception.” Lorenz was the first to show that certain chaotically manifesting behaviors are nevertheless determined by a strict (and sublime) order and can be visually represented in phase space. Hidden beneath the apparent chaos of the superficial experience of the wheel is an aesthetically magnificent order of universal forms, in many ways reminiscent of Plato’s ideal world. The quantum physicists also arrived at Plato’s famous ideal world, albeit via a different route. Heisenberg expressed this in perhaps the most direct way: “I think that modern physics has definitely decided in favor of Plato. The smallest units of matter are not objects in the ordinary sense; they are forms, ideas.…”

グリックは述べました:「物理システムの位相空間ポートレートは,他の方法では見えなかった動きのパターンを明らかにします。それは、赤外線の風景写真が知覚の及ばないところに存在するパターンや詳細を明らかにすることに似ています。」 ローレンツは、ある種のカオス的に現れる動作が、厳密な(そして崇高な)秩序によって決定され、位相空間で視覚的に表現できることを初めて明らかにしました。表面的なカオスの下に、プラトンの理想郷を思わせるような、美学的に壮大な秩序が隠されていました。量子物理学者もまた、プラトンの有名な理想郷に、別のルートで到達しました。 ハイゼンベルクは、そのことを最も端的に表現しています:「現代物理学は間違いなくプラトンを支持することになったと思う。 物質の最小単位は、通常の意味での物体ではなく、形であり、観念である......」と。

This is without doubt the most important lesson that the waterwheel has to teach us: We cannot predict the specific behaviors of the waterwheel (at least not in its chaotic phase), but we can learn the principles by which it behaves and learn to sense the sublime aesthetic figures hidden beneath the chaotic surface of those behaviors. Hence, there is no rational predictability, but there is a certain degree of intuitive predictability. In 1914 already, Henri Poincaré argued that logical understanding is not always necessary to intuitively understand some phenomena and to make predictions based on one’s intuition. It is possible to accurately sense the globality of the underlying structure of a phenomenon—for example the Lorenz attractor—without having any significant logical understanding of that phenomenon. Poincaré even went a step further, stating that pursuing logical knowledge about the phenomenon might, once a certain point is reached, be counterproductive. When confronted with the irrational aspect of a phenomenon, the persistence to obtain rational understanding will prevent us from coming to conclusions based on more direct receptiveness.

これは間違いなく、水車が私たちに教えてくれる最も重要な教訓です:水車の具体的な挙動を予測することはできませんが(少なくともカオス相においては)、その挙動の原理を学び、その挙動のカオス的な表面の下に隠された崇高な美の姿を感じ取ることはできます。 すなわち、合理的な予測可能性はないが、ある程度の直感的な予測可能性はあります。アンリ・ポアンカレは、1914年の段階で、ある現象を直感的に理解し、その直感に基づいた予測をするためには、必ずしも論理的な理解が必要ではないと論じました。ある現象(例えばローレンツ・アトラクターなど)の根底にある構造の大域性を正確に感じ取るために、その現象について大した論理的理解がなくとも可能なのだと。ポアンカレはさらに踏み込んで、現象に関する論理的な知識を追求することは、ある段階に到達すると逆効果になる可能性があるとさえ述べています。ある現象の非合理的な側面に直面したとき、合理的な理解を得ることに執着すると、より直接的な受容性に基づく結論に至ることができなくなります。

The way in which you experience the wheel as a spectator will strongly depend on the level at which your attention is focused. If you look at each isolated movement or motion sequence separately, the movements are perceived as chaotic and disparate. The wheel seems like a cacophony of abruptly interrupted back and forth movements. However, if you are able to feel affinity with the wheel and get to sense the deeper rhythms present in the variety of movements (as represented in the figure of the Lorenz attractor), then you experience the timeless, creative harmony that is present underneath the variety of superficial movements and the wheel becomes an appeasing phenomenon.

観客として水車をどのように体験するかは,あなたの注意をどのレベルに集中させるかに強く依存します。それぞれの孤立した動きや一連の動きを別々に見ると、動きは混沌としてバラバラなものとして認識されます。 水車は,突然に中断される前後運動の不協和音に見えます。しかし、もしあなたが車輪との親和性を感じ、(ローレンツ・アトラクターの図に表されるように)多様な動きの中に存在する深いリズムを感じ取ることができたなら、表面的な動きの中にある時間を超えた創造的な調和を感じることができ、車輪が心地よい現象になるります。

In this respect, the wheel teaches us something that applies to a far broader extent to the human being, society, life, and nature. Just like the wheel, most phenomena in nature are complex and dynamic and, in their complexity, are rather unpredictable. But like the wheel, life follows certain principles and sublime phenomena are hidden beneath its seemingly chaotic surface. And this is perhaps a person’s greatest task: to discover the timeless principles of life, in and through all the complexity of existence. The better we can sense those principles, the more we feel that we start to understand some of the essence of life and that we are connected with the majestic, ordering principle that speaks to us from across the universe. And the more we stick to our principles, even if it seems to our own detriment in the short term, the more real these principles become and the more we develop, as human beings, a real sense of existence and fortitude. Being too opportunistic and relinquishing our principles because “smart” analysis of a situation suggests it might be advantageous, often leads to a loss of individuality and experiences of meaninglessness. If one focuses too much on the superficial appearances of life and loses touch with the underlying principles and figures, life will increasingly be experienced as a meaningless chaos, just like Lorenz’s waterwheel.

この点で、水車は、人間、社会、人生、そして自然など、はるかに広く当てはまることを教えてくれます。 自然界のほとんどの現象は、水車と同じように複雑かつ動的であり、その複雑さゆえに予測不可能です。 しかし、水車のように、生命は一定の法則に従っており、一見無秩序に見えるその表面には崇高な現象が隠されています。 そして、この複雑な存在の中に、時代を超えた生命の原理を見いだすことこそ、人間の最大の課題です。 その原理を感じ取ることができればできるほど、私たちは生命の本質の一端を理解し始め、宇宙の彼方から語りかけてくる壮大な秩序原理とつながっていることを実感することができるのです。 そして、たとえ短期的には自分の不利益になるようなことでも、原理原則を貫けば貫くほど、その原理原則は現実のものとなり、人間として本当の意味での存在感と不屈の精神が育まれるのです。 しかし、「賢い」(小賢しい)分析にり有利になりそうだからといって、その場しのぎで主義主張を放棄してしまうと、個性を失い、無意味な経験をしてしまうことが多いのです。 もし、人生の表面的な姿にこだわりすぎて、その根底にある原理や図式を見失えば、人生はローレンツの水車のように意味のないカオスと化してしまうでしょう。

The same applies at the societal level: A society primarily has to stay connected with a number of principles and fundamental rights, such as the right to freedom of speech, the right to self-determination, and the right to freedom of religion or belief. If a society fails to respect these fundamental rights of the individual, if it allows fear to escalate to such an extent that every form of individuality, intimacy, privacy, and personal initiative is regarded as an intolerable threat to “the collective well-being,” it will decay into chaos and absurdity. The belief in the mechanistic nature of the universe and the associated overestimation of the powers of human intellect, typical of the Enlightenment, were accompanied by a tendency to lead society in a less and less principled manner. Within a purely mechanistic way of thinking, it is extremely difficult (not to say impossible) to ground ethical principles. Why should a machine man in a machine universe have to adhere to principles and ethical rules in relationships with others? Isn’t it ultimately about being the fittest in the struggle for survival? And therefore, aren’t ethics and principles a hindrance rather than a merit? In the final analysis, it was no longer a question for Enlightenment people to adhere to commandments and prohibitions or ethical and moral principles, but to move through this struggle for survival in the most efficient way possible based on “objective knowledge” of the world. This culminated in totalitarian and technocratic forms of government, where decisions are not made on the basis of generally applicable laws and principles but on the basis of the analysis of “experts.” For this reason, totalitarianism always chooses to abolish laws, or fails to implement them, and prefers to rule “by decree.” This means that, each new situation will require the formulation of new rules on the basis of a (pseudo)rational assessment of such situation. History abundantly illustrates that this leads to erratic, absurd, and ever-changing rules, which ultimately destroy all humanity in society.

社会的なレベルでも同様です: まずもって、社会は、言論の自由の権利、自己決定の権利、宗教または信仰の自由の権利など、多くの原則と基本的権利と結びついていなければなりません。 もし社会がこれらの個人の基本的権利を尊重せず、これらの権利(あらゆる形の個性、親密さ、プライバシー、個人の自発性)が「集団の幸福」に対する耐え難い脅威とみなされるほど恐怖がエスカレートするのなら、社会は混沌と不条理で崩壊するでしょう。 社会がますます無原則な方法で導かれると、機械論的宇宙観に対する信念と、それに伴う人間の知性の力の過大評価(啓蒙主義の典型的)が助長されています。純粋に機械論的な思考では、倫理的な原則を確立することは(不可能とは言わないまでも)極めて困難です。 なぜ、機械宇宙に生きる機械人間が、他者との関係において、原理や倫理的ルールを尊重せねばならないのでしょうか?究極的に、生存競争における適者生存では無いのでしょうか?それゆえ、倫理や原則は、利点ではなく、障害では有りませんか?最終的には、啓蒙主義者にとっての問題は、もはや戒律や禁止事項、倫理や道徳の原則を守ることではなく、世界の「客観的知識」に基づいて、この生存競争を最も効率的な方法で進めることだったのです。 その結果、一般に適用可能な法律や原則ではなく、「専門家 」の分析に基づいて意思決定が行われる全体主義的・技術主義的な政治形態に行き着いたのですこのため、全体主義は常に法律(law)を打破し、あるいは法律化を阻み、、「命令」(decree)による 支配を好みます。つまり、新しい状況が生まれるたびに、その状況に対する(疑似的な)合理的評価に基づいて、新しい規則を策定することが必要になります。 このことが、不規則で不条理で、絶えず変化する規則をもたらし、最終的に社会のすべての人間性を破壊することを、歴史は十分に示しています。

This is perhaps the most direct and concrete illustration of Hannah Arendt’s thesis that ultimately totalitarianism is the symptom of a naive belief in the omnipotence of human rationality. Therefore, the antidote to totalitarianism lies in an attitude to life that is not blinded by a rational understanding of superficial manifestations of life and that seeks to be connected with the principles and figures that are hidden beneath those manifestations.

これは、ハンナ・アーレントのテーゼである「全体主義とは、究極的には人間の合理性の全能性に対する素朴な信仰の症状である」を、最も直接的かつ具体的に示していると言えるでしょう。したがって、全体主義に対する解毒剤は、人生の表面的な現れに対する合理的な理解によって盲目になることなく、その下に隠された原理や姿と結びつこうとする人生に対する態度にあるのです。

Chaos theory and the complex and dynamic systems theory open a breathtaking new perspective on the universe. In his widely acclaimed book Chaos, Gleick states that chaos theory is the third great scientific revolution of the twentieth century (after the relativity theory and quantum mechanics). Mechanistic-materialistic science started from the assumption that the world is logical and predictable and, in particular, that it essentially is a dead mechanical process. Science aimed to reduce living phenomena—the organic, the consciousness, etc.—to dead processes (for example, to mechanical chemical processes). Quantum mechanics and chaos theory shake this worldview. They initiated the reverse momentum and lean much more toward a vitalist worldview. They suggest that there is life and consciousness in all kinds of phenomena that we previously considered to be dead, mechanical processes. Think of the noise on telephone lines: It proved to not be the passive effect of all kinds of mechanical factors, but to be self-organizing; it is characterized by purposefulness and a sense of aesthetics.

カオス理論や複雑系・動的系理論は、宇宙に対する息を呑むような新しい視点を提供します。グリック氏は、広く評価されている著書『カオス』の中で、カオス理論が(相対性理論、量子力学に続く)20世紀における第三の偉大な科学革命であると述べています。機械論的・唯物論的科学は、世界が論理的で予測可能であり、特に、本質的には無生命な機械的プロセスであるという仮定から出発しました。 科学は、有機物や意識などの生命現象を、無生命なプロセス(例えば、機械的な化学プロセス)に還元することを目指した。 量子力学とカオス理論は、この世界観を揺るがしました。彼らは逆方向の考え方を主導し、生命論的な世界観に傾倒しました。これまで無生命な機械的過程と考えられていたあらゆる現象に、生命や意識があることを示唆しています。 電話線のノイズを考えてみてください。 それは、あらゆる機械的要因の受動的な影響ではなく、自己組織化されたものであることが証明されました。それは、目的意識と美意識によって特徴づけられています。

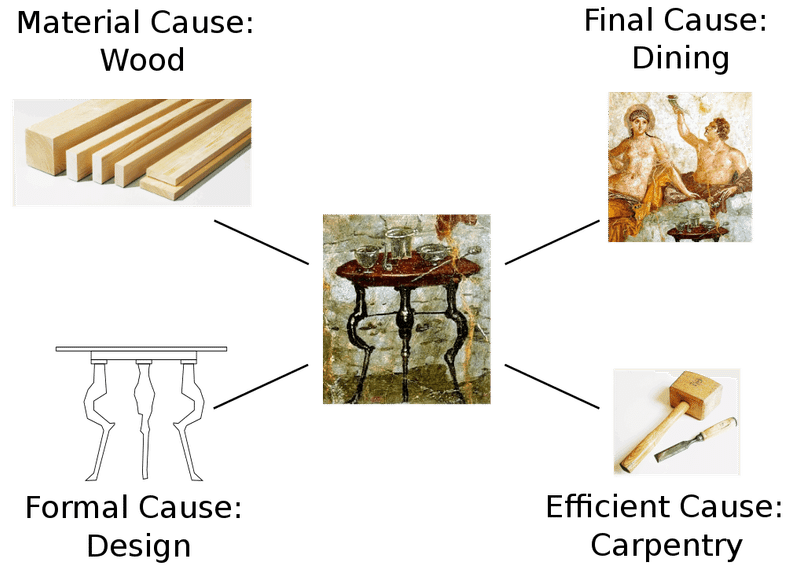

Perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of chaos theory is that its observations allow us to see that there is indeed a final and formal cause at work in nature. These concepts are derived from the causality theory of Aristotle and are indispensable when considering the process of causation. In a nutshell, this theory states that there are four kinds of causes: the material, the efficient, the formal, and the final. Aristotle illustrated the difference between these four causes using the metaphor of making a statue. The material cause of the statue is the matter from which it is made (without such matter, no statue). The efficient cause is the movements of the sculptor, who uses chisel and hammer to transform the stone into a statue. The formal cause is the idea or form of the statue as it has taken form in the mind of the sculptor and determines how he will direct his movements. The final cause is the intention to make a statue (for example, because someone has ordered a statue from the sculptor). It is clear that, within a mechanistic worldview, only the material and the efficient cause are considered to be active. Once upon a time, the mechanistic universe, as a collection of material particles, set itself in motion, and all the rest followed from the initial movement of the particles. So the particles in themselves are the material cause; their movements, which generate all kinds of effects, are the efficient cause. However, within such a worldview, it cannot be presumed that certain “forms” or “ideas” exist in advance (those of certain organisms, for example) that would influence the way the material process unfolds.

カオス理論の最も画期的な点は、その観察によって、自然界には最終的かつ形式的な原因が確かに働いていることを確認できることです。 これらの概念は、アリストテレスの因果論から派生したもので、因果の過程を考える上で欠くことのできないものであす。 この理論は、原因には物質的原因、効率的原因、形式的原因、最終的原因の4種類があるとするものです。 アリストテレスは、この4つの原因の違いを、彫像を作るという比喩を使って説明しました。 像の物質的な原因は、像が作られる物質です(そのような物質がなければ、像は作れない)。 効率的原因は、彫刻家の動きであり、彫刻家はノミとハンマーを使って石を彫像に変形させることです。 形式的な原因は、彫刻家の心の中にある像のアイデアや形であり、彫刻家がどのように 動作を指示するかを決定するものです。最終的な原因は、彫像を作るという意図です(例えば、誰かが彫刻家に彫像を注文し たから)。 機械論的な世界観の中では、物質的原因と効率的原因のみが能動的であると考えられました。 昔々、機械論的宇宙は、物質的な粒子の集まりとして、自ら動き出し、残りのすべて は、粒子の最初の動きから続いて起こったのでした。 つまり、粒子それ自体が物質的原因であり、その運動があらゆる効果を生み出すというのが効率的原因です。 しかし、このような世界観では、物質的なプロセスの展開に影響を与える様な、ある種の「形」や「考え」(例えば、ある種の生物のそれ)があらかじめ存在することは想定されていません。

Chaos theory proves that such forms do exist and that they operate in a coordinated manner. What has been demonstrated with the noise on telephone lines and drops dripping out of faucets can be broadened to a much larger scope. Chaos theory shows us that the mountain landscape that transports us in breathless admiration is not simply the effect of a lifeless mechanistic process—accidental mechanistic processes between tectonic plates, erosion, and eruptions of lava—but that a timeless and sublime idea coordinated the myriad of mechanical processes involved in its formation. Chaos theory heralds, maybe even more than quantum mechanics, the era that historically and logically follows the Enlightenment; an era when the universe is once again pregnant with meaning.

カオス理論は、そのような(因果論的な)形態が実際に存在し、それらが協調して動作していることを証明しています。電話線のノイズや蛇口から滴り落ちる雫で証明されたことは、もっと大きな範囲に拡大することができます。カオス理論は、私たちを感嘆させる山の風景が、単に生命のない機械的プロセス(地殻プレート間の偶然の機械的プロセス、侵食、溶岩の噴出)によるものではなく、時代を超えた崇高なアイデアが、その形成に関わる無数の機械プロセスを調整していることを示しているのです。カオス理論は、量子力学以上に、啓蒙主義に続く歴史的・論理的な時代の到来を告げています。つまり、宇宙が再び意味を孕んでいる時代です。

全体構成

Part I: Science and its Psychological Effects

Part II: Mass Formation and Totalitarianism

Part III: Beyond the Mechanistic Worldview

この記事が気に入ったらサポートをしてみませんか?